Volumes in her Aunt Jo’s Scrap-Bag series of short-story collections found their way under many a Christmas tree. (From the collection of the editor)

A gap of both manners and experience of the world divides the narrator from Jo, who proudly retains her penchant for slang, her boyish carriage, and other rough edges through most of the novel. Jo the middle-aged storyteller, with her superior knowledge and periodic asides to the reader, supplies not only a narrative structure to the book but also a moral one; we depend on both her and Marmee to explain the ethics of unfolding situations. At the same time that the narrating Jo imposes order, the younger Jo disrupts it. Though not nearly as wise as the woman she will later become, the young Jo does know her own mind, and she speaks it fluently. She also knows things that the narrator can approach only through memory: what it is to be young, awkward, and filled with misgivings about growing up. The narrating Jo shapes the story with her experienced mind; young Jo enlivens it with the energy of her body and the frankness of her spirit. In Little Men and Jo’s Boys, the gap in age and experience between Jo and the writer who creates her inevitably narrows. If the latter two books of the trilogy are less compelling than the first, they may be so in large part because the youthful voice and its older counterpart gradually merge, and the tension between the two Jos naturally evaporates.

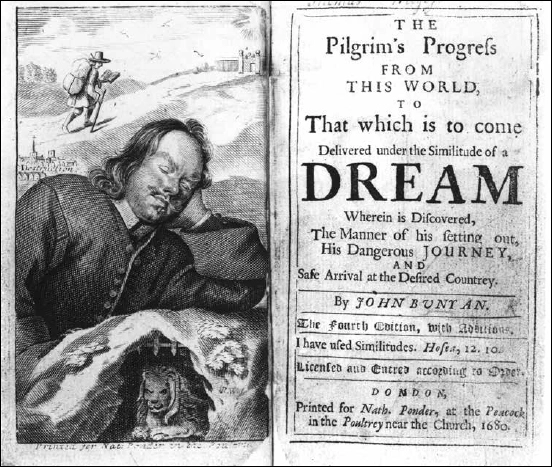

Bronson Alcott called The Pilgrim’s Progress one of his “bosom companions,” and he frequently read aloud from it to his daughters. Louisa consciously used the book as a model for Little Women. (Houghton Library, Harvard University)

As was briefly noted earlier, Alcott used Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress as a kind of trellis to structure the story of Little Women. Like Alcott’s novel, Bunyan’s allegory tells of moral transformation. Bunyan’s narrator recounts his dream of Christian, a man who, tormented by presentiments of the destruction that awaits the sinful, abandons his wife and children to pursue righteousness. Bunyan represents Christian’s striving toward purification as a physical journey. The trials and temptations the hero encounters are figured either as physical places (depression becomes the Slough of Despond; the enticements of lust and greed call out to him at Vanity Fair) or as dreadful monsters (Christian strives with wrath in the form of the giant Apollyon and must ignore the advice of false friends like Timorous and Mistrust). In the company of brave companions like Faithful and Hopeful, Christian at last makes his way to the Celestial City. As is well known, each of the March sisters is defined early in the novel by a signature flaw that it is her task to overcome. Meg wrestles with vanity; Jo tries to subdue her temper; Beth seeks to surmount her shyness; and Amy slowly learns to become less selfish. In each instance, Alcott uses a chapter title to link the inner struggle to episodes from Bunyan: “Meg Goes to Vanity Fair”; “Jo Meets Apollyon”; “Beth Finds the Palace Beautiful”; and “Amy’s Valley of Humiliation.” Though Bunyan’s presence is especially strong in the first dozen chapters that Alcott drafted at Niles’s behest, it remains a motif quite deep into the novel: “Pleasant Meadows,” the title of the chapter in which Mr. March comes home, is also borrowed from Bunyan, and the chapter that relates Beth’s passing, “The Valley of the Shadow,” is a nod both to Bunyan and the Twenty-third Psalm. Alcott’s reliance on Pilgrim’s Progress was neither random nor superficial. Bunyan’s work had been firmly entwined with her family’s history, and it had taught her early in life the power that a single book can exert over a human life.

The son of an illiterate farmer, Louisa’s father Bronson came into awareness in a home without books. He was eager for education, though, and he slowly amassed a library from the literary castoffs of neighboring farmers. From a helpful cousin, he repeatedly borrowed a copy of The Pilgrim’s Progress and committed favorite passages to memory. He called it his “dear, delightful book” and said that “more than any work of genius, more than all other books, the Dreamer’s Dream brought me into living acquaintance with myself.” Bronson took to heart with uncommon zeal the spiritual message of The Pilgrim’s Progress, a message that emphasized that the way to salvation is hard and narrow and that one does not follow it either by indulging in the carnal pleasures of this life or by being ruled by the good opinions of others. Bronson absorbed a profound wariness of material temptations and a firm resistance to popular opinion. He also believed that he had been put on earth to raise to their highest perfection the minds and souls of the people around him. As a father, Bronson dispensed readings from The Pilgrim’s Progress to his children along with their gingerbread. Throughout his career as a teacher, he continually impressed upon his young charges the Bunyanesque values of holy community and self-denial. When that career abruptly ended in 1839, he redoubled the lessons of charity and personal austerity that he taught his own children.

1 comment