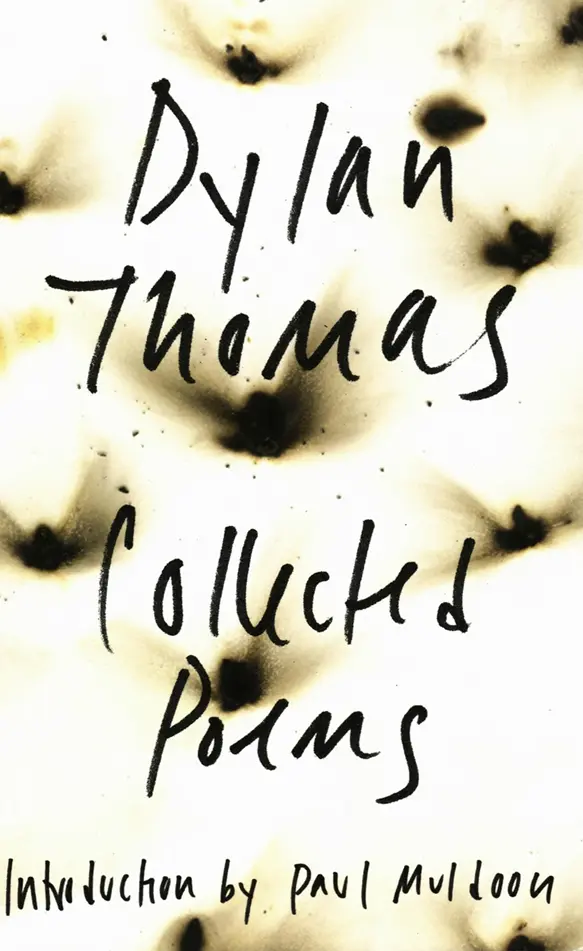

The Collected Poems of Dylan Thomas

THE

COLLECTED

POEMS

OF

DYLAN

THOMAS

ORIGINAL EDITION

Introduction By Paul

Muldoon

A NEW

DIRECTIONS BOOK

CONTENTS

Dylan and

Delayment

by Paul

Muldoon

Author’s Note

Prologue

I see the boys

of summer

When once the twilight locks no longer

A process in the weather of the heart

Before I

knocked

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

My hero

bares his nerves

Where once the waters of your face

If I were tickled by the rub of love

Our eunuch

dreams

Especially when the October wind

When, like

a running grave

From love’s first fever to her plague

In the

beginning

Light breaks where no sun shines

I fellowed

sleep

I

dreamed my genesis

My world

is pyramid

All all and all the dry worlds lever

I,

in my intricate image

This bread I

break

Incarnate

devil

Today, this

insect

The

seed-at-zero

Shall gods be said to thump the clouds

Here in

this spring

Do you

not father me

Out of the

sighs

Hold hard, these ancient minutes in the cuckoo’s

month

Was there a

time

Now

Why east wind

chills

A grief ago

Ears

in the turrets hear

How

soon the servant sun

Foster the

light

The

hand that signed the paper

Should

lanterns shine

I have

longed to move away

Find meat on

bones

Grief thief of

time

And death shall have no dominion

Then was my

neophyte

Altarwise

by owl-light

Because the pleasure-bird whistles

I

make this in a warring absence

When all my five and country senses see

We lying

by seasand

It is the sinners’ dust-tongued bell

O make me a

mask

The spire

cranes

After the

funeral

Once it was the colour of saying

Not from

this anger

How shall my

animal

The tombstone told when she died

On no work of

words

A saint

about to fall

‘If my head hurt a hair’s foot’

Twenty-four

years

The conversation of prayers

A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London

Poem in

October

This side

of the truth

To Others

than You

Love in the

Asylum

Unluckily for a death

The

hunchback in the park

Into her

lying down head

Do not go gentle into that good night

Deaths

and Entrances

A Winter’s

Tale

On a

Wedding Anniversary

There was

a saviour

On

the Marriage of a Virgin

In my

craft or sullen art

Ceremony After a Fire Raid

Once below a

time

When I woke

Among those Killed in the Dawn Raid was a Man Aged a

Hundred

Lie

still, sleep becalmed

Vision and

Prayer

Ballad of the Long-legged Bait

Holy Spring

Fern Hill

In Country

Sleep

Over Sir

John’s hill

Poem on His

Birthday

Lament

In

the White Giant’s Thigh

TWO UNFINISHED POEMS:

Elegy

Vernon

Watkins’s note

In Country

Heaven

Daniel

Jones’s note

A

Chronology

Index

of Titles and First Lines

to

Caitlin

DYLAN AND DELAYMENT

Dylan Thomas is that rare

thing, a poet who has it in him to allow us, particularly those of us who are coming to

poetry for the first time, to believe that poetry might not only be vital in itself but

also of some value to us in our day-to-day lives. It’s no accident, surely, that

Dylan Thomas’s “Do not go gentle into that good night” is a poem which

is read at two out of every three funerals. We respond to the sense in that poem, as in

so many others, that the verse engine is so turbocharged and the fuel of such high

octane that there’s a distinct likelihood of the equivalent of vertical liftoff.

Dylan Thomas’s poems allow us to believe that we may be transported, and that

belief is itself transporting.

Oddly, one of the main obstacles to readers immediately reaching the speed of sound,

maybe even of light, is Dylan Thomas’s own tabloidian history. Like some of his

poems, Dylan Thomas had a habit of putting some things off, be it getting a job or

paying the rent. It was, however, his not postponing an eighteenth straight whiskey in

the White Horse Tavern that would lead to his death on November 9, 1953 at the age of

39. Paradoxically, it confirmed his already legendary status as the artist as old dog,

the poet as shaman-bard. One’s reminded of Michael Drayton’s notion,

expressed in his Poly-Olbion, of the furor poeticus

which he associates with the Welsh bards in their “sacred rage,” singing to

a harp accompaniment “with furie rapt.”

That sense of the history of the Welsh bard was instilled from the start in Dylan Mariais

Thomas, born on October 27, 1914 in Swansea. The “Marlais” was the name used

by his great uncle, William Thomas, in his own bardic forays and means something like

“great blue-green.” It’s a name shared by two Welsh rivers, and along

with the meaning of Dylan itself (“son of the sea”) might be thought of as

predisposing the poet to an extraordinary combination of fluency and force. We read the

last line of “Fern Hill” (“Though I sang in my chains like the

sea”) with quite a new attentiveness.

“Fern Hill” was written in 1945, when Dylan was at the height of his powers,

and might be said to be typical of his “mature” style:

Now as I was young and easy under the apple

boughs

About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green

The night above the dingle starry,

Time let me hail and climb

Golden in the heydays of his eyes,

And honored among wagons I was prince of the apple towns

And once below a time I lordly had the trees and leaves

Trail with daisies and barley

Down the rivers of the windfall light.

The “chains” in which this poet

sings have, in some sense, been loaded upon him by himself. Like Marianne Moore, Thomas

is engaged in a system of syllables, this first stanza establishing a pattern of lines

of 14, 14, 9, 6, 10, 15, 14, 7 and 9 syllables to which the poem adheres, sort of, in

the highly modified way a sea might be expected to be contained by its chains. Such full

end-rhymes as the poem displays (“stars” and “jars” in stanza 3,

“white” and “light” in stanza 4, “long” and

“songs” in stanza 5, “hand” and “land” in stanza 6) seem almost inadvertent, yet there are internal

rhymes and echoes into which a lot of thought has been put. This delight in language

play from line to line is a feature of Welsh prosody. We see it there in the internal

rhyme on “boughs” and “about” in lines 1 and 2, or in

“hail” and “heydays” in lines 4 and 5, as a kind of technical

delayment, or withholding, which is at the heart of Dylan Thomas’s formal

method.

Another example of this may be found in the term “heydays” in stanza I, which

anticipates the days spent making “hay,” both the subjects of stanzas 3 and

5. Such punning, which is itself another form of delayment in the sense of

“hindrance,” where one meaning of a word intervenes before another, may be

found in a word like “lilting,” which rather neatly combines the sense of a

house in which one might hear someone “sing cheerfully or merrily”

(OED) as well as a house that is “tilting.” A more conventional

form of punning is available in the word “down,” which extends to both the

senses of “descending direction” and “any substance of a feathery or

fluffy nature” such as that one might find on barley, the word with which it is

violently enjambed. Those “whiskers” that are a feature of barley bring to

mind the beardless condition of someone who is “young and easy.”

The combination of the words “down” and “young and easy” conjures

up a setting which might be described as a diorama for “Fern Hill.”

It’s the setting of W. B. Yeats’s beautiful lyric “Down By

the Salley Gardens,” in which there is a great deal of shared vocabulary with the

first stanza of “Fern Hill,” including not only “down,”

“young,” and “easy” but also “trees,”

“leaves,” “river,” and “grass.” A Yeatsian influence

extends to the “apple boughs” in line I, apple boughs being a feature of any

number of Yeats poems including “The Song of the Wandering Aengus,” in which

Aengus proposes to pluck “the silver apples of the moon, / the golden apples of

the sun.” The word “wanderer” appears in stanza 4 of “Fern

Hill,” while the first word of line 5 in both stanzas 1 and 2 is

“golden”. The fact that Thomas establishes such a pattern in stanzas 1 and

2, just as he uses the phrase “happy as the heart was long” at the end of

line 2 of stanza 5, replicating the phrase “happy as the grass was green” at

the end of line 2 of stanza 1, suggests that he might have harbored Yeatsian ambitions

in the business of stanza-making. Again, it’s an ambition he defers.

The spirit of Yeats is not the only one that threatens to loom between us and our

capacity to read Dylan Thomas in his craft or sullen art:

In my craft or sullen

art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers

lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labor by singing

light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the

ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.

Written in 1945, “In my craft or sullen

art” owes much to W. H. Auden’s “Lullaby,” written in 1937, with

which it shares some key vocabulary—“lie,” “arms,”

“night,” “heart”—as well as the 7-syllable line count and

something of the rhythm of part III of Auden’s 1939 “InMemory of W. B.

Yeats”:

In the deserts of the

heart

Let the healing fountain start,

In the prison of his days

Teach

the free man how to praise.

This rhythm is, of course, derived from

Yeats’s own “Under Ben Bulben”:

Irish poets

learn your trade

Sing whatever is well made.

The “trade” has itself been lifted

wholesale from “Under Ben Bulben” to the “trade of

charms,” while the “strut” in the same line may be traced to

“there struts Hamlet” of “Lapis Lazuli,” a poem in which the

rhyme “rages / stages” appears as in “In my craft or sullen

art.” “Strut” is a word that has a walk-on part, as it were, in

another of Thomas’s greatest poems, “After the funeral,” with its

stunning closing:

These cloud-sopped, marble

hands, this monumental

Argument of the hewn voice, gesture and psalm,

Storm me

forever over her grave until

The stuffed lung of the fox twitch and cry

Love

And the strutting fern lay seeds on the black sill.

Although something of the power of that image is

diminished if one remembers the “fern-seed footprints” so delicately made by

Marianne Moore’s “The Jerboa,” which had appeared in her Selected

Poems of 1935, it nonetheless represents Thomas at his own swaggering best.

This tendency towards brashness, along with those towards bluster and browbeating, may

account for the slightly reticent quality of Marianne Moore’s comments on him for

the issue of The Yale Review that coincided with the first anniversary of

Thomas’s death. In November 1954, Moore described Thomas in a kind of boilerplate

praise-speak:

He was true to his gift and he had a mighty power, indigenously

accurate like nature’s. And his mechanism at times is as precise as the

content.

There seems to be a suggestion on the part of

Moore (underscored by her own uncharacteristically lumpish prose) that there’s

another type of delayment all too often to be found in Dylan Thomas

which has to do with his style more often than not hampering his subject-matter, only

occasionally allowing a poem to sing out of its chains.

Even when a single stretch of a poem by Dylan Thomas is muddied by its influences,

including the omnipresent Joyce, extending to usages such as “dingle” and

“windfall” and the funster garbling of “happy as the grass was

green” and “once below a time,” there is nonetheless something sweet

and clear and refreshing flowing through that same stretch. We find it in the gorgeous

“And honored among wagons I was prince of the apple towns,” which comes off

the page as being oddly balanced rather than bodacious, as Dylan Thomas and no one

else.

Dylan Thomas once remarked of posterity that its function should be “to look after

itself.” As part of our looking after ourselves we should acknowledge the

possibility that what has sometimes come between Thomas’s poems and our capacity

to read them is as much our own sense of being “lordly” over his being

“loudly,” a fashionable looking down one’s nose at his tendency

towards high spirits, including those legendary eighteen straight whiskies. When we tear

away the tabloidian tissue there is revealed a poet who has overcome so much—his

influences, his being under the influence—that our impulse to reach for him when our own

sense of the world is obstructed or obscured turns out to have been well founded.

PAUL MULDOON

NOTE

The prologue in verse, written

for this collected edition of my poems, is intended as an address to my readers, the

strangers.

This book contains most of the poems I have written, and all, up to the present year,

that I wish to preserve. Some of them I have revised a little, but if I went on revising

everything that I now do not like in this book I should be so busy that I would have no

time to try to write new poems.

I read somewhere of a shepherd who, when asked why he made, from within fairy rings,

ritual observances to the moon to protect his flocks, replied: ‘I’d be a

damn’ fool if I didn’t!’ These poems, with all their crudities,

doubts, and confusions, are written for the love of Man and in praise of God, and

I’d be a damn’ fool if they weren’t.

DYLAN

THOMAS

LAUGHARNE, WALES, NOVEMBER 1952

PROLOGUE

This day winding down now

At God speeded summer’s end

In the torrent salmon sun,

In my seashaken house

On a breakneck of rocks

Tangled with chirrup and fruit,

Froth, flute, fin and quill

At a wood’s dancing hoof,

By scummed, starfish sands

With their fishwife cross

Gulls, pipers, cockles, and sails,

Out there, crow black, men

Tackled with clouds, who kneel

To the sunset nets,

Geese nearly in heaven, boys

Stabbing, and herons, and shells

That speak seven seas,

Eternal waters away

From the cities of nine

Days’ night whose towers will catch

In the religious wind

Like stalks of tall, dry straw,

At poor peace I sing

To you strangers, (though song

Is a burning and crested act,

The fire of birds in

The world’s turning

wood,

For my sawn, splay sounds),

Out of these sea thumbed leaves

That will fly and fall

Like leaves of trees and as soon

Crumble and undie

Into the dogdayed night.

Seaward the salmon, sucked sun slips,

And the dumb swans drub blue

My dabbed bay’s dusk, as I hack

This rumpus of shapes

For you to know

How I, a spinning man,

Glory also this star, bird

Roared, sea born, man torn, blood blest.

Hark: I trumpet the place,

From fish to jumping hill! Look:

I build my bellowing ark

To the best of my love

As the flood begins,

Out of the fountainhead

Of fear, rage red, manalive,

Molten and mountainous to stream

Over the wound asleep

Sheep white hollow farms

To Wales in my arms.

Hoo, there, in castle keep,

You king singsong owls, who

moonbeam

The flickering runs and dive

The dingle furred deer dead!

Huloo, on plumbed bryns,

O my ruffled ring dove

In the hooting, nearly dark

With Welsh and reverent rook,

Coo rooing the woods’ praise,

Who moons her blue notes from her nest

Down to the curlew herd!

Ho, hullaballoing clan

Agape, with woe

In your beaks, on the gabbing capes!

Heigh, on horseback hill, jack

Whisking hare! who

Hears, there, this fox light, my flood

ship’s

Clangour as I hew and smite

(A clash of anvils for my

Hubbub arid fiddle, this tune

On a tongued puffball)

But animals thick as thieves

On God’s rough tumbling grounds

(Hail to His beasthood!).

Beasts who sleep good and thin,

Hist, in hogsback woods! The haystacked

Hollow farms in a throng

Of waters cluck and

cling,

And barnroofs cockcrow war!

O kingdom of neighbours, finned

Felled and quilted, flash to my patch

Work ark and the moonshine

Drinking Noah of the bay,

With pelt, and scale, and fleece:

Only the drowned deep bells

Of sheep and churches noise

Poor peace as the sun sets

And dark shoals every holy field.

We will ride out alone, and then,

Under the stars of Wales,

Cry, Multitudes of arks! Across

The water lidded lands,

Manned with their loves they’ll move,

Like wooden islands, hill to hill.

Huloo, my prowed dove with a flute!

Ahoy, old, sea-legged fox,

Tom tit and Dai mouse!

My ark sings in the sun

At God speeded summer’s end

And the flood flowers now.

THE COLLECTED POEMS

OF

DYLAN THOMAS

ORIGINAL EDITION

I SEE THE BOYS OF SUMMER

I

I see the boys of summer in their ruin

Lay the gold tithings barren,

Setting no store by harvest, freeze the soils;

There in their heat the winter floods

Of frozen loves they fetch their girls,

And drown the cargoed apples in their tides.

These boys of light are curdlers in their

folly,

Sour the boiling honey;

The jacks of frost they finger in the hives;

There in the sun the frigid threads

Of doubt and dark they feed their nerves;

The signal moon is zero in their voids.

I see the summer children in their mothers

Split up the brawned womb’s weathers,

Divide the night and day with fairy thumbs;

There in the deep with quartered shades

Of sun and moon they paint their dams

As sunlight paints the shelling of their heads.

I see that from these boys shall men of nothing

Stature by seedy shifting,

Or lame the air with leaping from its heats;

There from their hearts the dogdayed pulse

Of love and light bursts in their throats.

O see the pulse of summer in the ice.

II

But seasons must be challenged or they totter

Into a chiming quarter

Where, punctual as death, we ring the stars;

There, in his night, the black-tongued bells

The sleepy man of winter pulls,

Nor blows back moon-and-midnight as she blows.

We are the dark deniers, let us summon

Death from a summer woman,

A muscling life from lovers in their cramp,

From the fair dead who flush the sea

The bright-eyed worm on Davy’s lamp,

And from the planted womb the man of straw.

We summer boys in this four-winded spinning,

Green of the seaweeds’ iron,

Hold up the noisy sea and drop her birds,

Pick the world’s ball of wave and froth

To choke the deserts with her tides,

And comb the county gardens for a wreath.

In spring we cross our foreheads

with the holly,

Heigh ho the blood and berry,

And nail the merry squires to the trees;

Here love’s damp muscle dries and dies,

Here break a kiss in no love’s quarry.

O see the poles of promise in the boys.

III

I see you boys of summer in your ruin.

Man in his maggot’s barren.

And boys are full and foreign in the pouch.

I am the man your father was.

We are the sons of flint and pitch.

O See the poles are kissing as they cross.

WHEN ONCE THE TWILIGHT LOCKS NO LONGER

When once the twilight locks no

longer

Locked in the long worm of my finger

Nor dammed the sea that sped about my fist,

The mouth of time sucked, like a sponge,

The milky acid on each hinge,

And swallowed dry the waters of the breast.

When the galactic sea was sucked

And all the dry seabed unlocked,

I sent my creature scouting on the globe,

That globe itself of hair and bone

That, sewn to me by nerve and brain,

Had stringed my flask of matter to his rib.

My fuses timed to charge his heart,

He blew like powder to the light

And held a little sabbath with the sun,

But when the stars, assuming shape,

Drew in his eyes the straws of sleep,

He drowned his father’s magics in a dream.

All issue armoured, of the grave,

The redhaired cancer still alive,

The cataracted eyes that filmed their cloth;

Some dead undid their bushy jaws,

And bags of blood let out their flies;

He had by heart the Christ-cross-row of death.

Sleep navigates the tides of

time;

The dry Sargasso of the tomb

Gives up its dead to such a working sea;

And sleep rolls mute above the beds

Where fishes’ food is fed the shades

Who periscope through flowers to the sky.

The hanged who lever from the limes

Ghostly propellers for their limbs,

The cypress lads who wither with the cock,

These, and the others in sleep’s acres,

Of dreaming men make moony suckers,

And snipe the fools of vision in the back.

When once the twilight screws were turned,

And mother milk was stiff as sand,

I sent my own ambassador to light;

By trick or chance he fell asleep

And conjured up a carcass shape

To rob me of my fluids in his heart.

Awake, my sleeper, to the sun,

A worker in the morning town,

And leave the poppied pickthank where he lies;

The fences of the light are down,

All but the briskest riders thrown,

And worlds hang on the trees.

A PROCESS IN THE WEATHER OF THE HEART

A process in the weather of the

heart

Turns damp to dry; the golden shot

Storms in the freezing tomb.

A weather in the quarter of the veins

Turns night to day; blood in their suns

Lights up the living worm.

A process in the eye forwarns

The bones of blindness; and the womb

Drives in a death as life leaks out.

A darkness in the weather of the eye

Is half its light; the fathomed sea

Breaks on unangled land.

The seed that makes a forest of the loin

Forks half its fruit; and half drops down,

Slow in a sleeping wind.

A weather in the flesh and bone

Is damp and dry; the quick and dead

Move like two ghosts before the eye.

A process in the weather of the world

Turns ghost to ghost; each mothered child

Sits in their double shade.

A process blows the moon into the sun,

Pulls down the shabby curtains of the skin;

And the heart gives up its dead.

BEFORE I KNOCKED

Before I knocked and flesh let

enter,

With liquid hands tapped on the womb,

I who was shapeless as the water

That shaped the Jordan near my home

Was brother to Mnetha’s daughter

And sister to the fathering worm.

I who was deaf to spring and summer,

Who knew not sun nor moon by name,

Felt thud beneath my flesh’s armour,

As yet was in a molten form,

The leaden stars, the rainy hammer

Swung by my father from his dome.

I knew the message of the winter,

The darted hail, the childish snow,

And the wind was my sister suitor;

Wind in me leaped, the hellborn dew;

My veins flowed with the Eastern weather;

Ungotten I knew night and day.

As yet ungotten, I did suffer;

The rack of dreams my lily bones

Did twist into a living cipher,

And flesh was snipped to cross the lines

Of gallow crosses on the liver

And brambles in the wringing brains.

My throat knew thirst before the

structure

Of skin and vein around the well

Where words and water make a mixture

Unfailing till the blood runs foul;

My heart knew love, my belly hunger;

I smelt the maggot in my stool.

And time cast forth my mortal creature

To drift or drown upon the seas

Acquainted with the salt adventure

Of tides that never touch the shores.

I who was rich was made the richer

By sipping at the vine of days.

I, born of flesh and ghost, was neither

A ghost nor man, but mortal ghost.

And I was struck down by death’s feather.

I was a mortal to the last

Long breath that carried to my father

The message of his dying christ.

You who bow down at cross and altar,

Remember me and pity Him

Who took my flesh and bone for armour

And doublecrossed my mother’s womb.

THE FORCE THAT THROUGH THE GREEN FUSE DRIVES THE

FLOWER

The force that through the green

fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees

Is my destroyer.

And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose

My youth is bent by the same wintry fever.

The force that drives the water through the

rocks

Drives my red blood; that dries the mouthing streams

Turns mine to wax.

And I am dumb to mouth unto my veins

How at the mountain spring the same mouth sucks.

The hand that whirls the water in the pool

Stirs the quicksand; that ropes the blowing wind

Hauls my shroud sail.

And I am dumb to tell the hanging man

How of my clay is made the hangman’s lime.

The lips of time leech to the fountain head;

Love drips and gathers, but the fallen blood

Shall calm her sores.

And I am dumb to tell a weather’s wind

How time has ticked a heaven round the stars.

And I am dumb to tell the lover’s tomb

How at my sheet goes the same crooked worm.

MY HERO BARES HIS NERVES

My hero bares his nerves along my

wrist

That rules from wrist to shoulder,

Unpacks the head that, like a sleepy ghost,

Leans on my mortal ruler,

The proud spine spurning turn and twist.

And these poor nerves so wired to the skull

Ache on the lovelorn paper

I hug to love with my unruly scrawl

That utters all love hunger

And tells the page the empty ill.

My hero bares my side and sees his heart

Tread, like a naked Venus,

The beach of flesh, and wind her bloodred plait;

Stripping my loin of promise,

He promises a secret heat.

He holds the wire from this box of nerves

Praising the mortal error

Of birth and death, the two sad knaves of thieves,

And the hunger’s emperor;

He pulls the chain, the cistern moves.

WHERE ONCE THE WATERS OF YOUR FACE

Where once the waters of your

face

Spun to my screws, your dry ghost blows,

The dead turns up its eye;

Where once the mermen through your ice

Pushed up their hair, the dry wind steers

Through salt and root and roe.

Where once your green knots sank their splice

Into the tided cord, there goes

The green unraveller,

His scissors oiled, his knife hung loose

To cut the channels at their source

And lay the wet fruits low.

Invisible, your clocking tides

Break on the lovebeds of the weeds;

The weed of love’s left dry;

There round about your stones the shades

Of children go who, from their voids,

Cry to the dolphined sea.

Dry as a tomb, your coloured lids

Shall not be latched while magic glides

Sage on the earth and sky;

There shall be corals in your beds,

There shall be serpents in your tides,

Till all our sea-faiths die.

IF I WERE TICKLED BY THE RUB OF LOVE

If I were tickled by the rub of

love,

A rooking girl who stole me for her side,

Broke through her straws, breaking my bandaged string,

If the red tickle as the cattle calve

Still set to scratch a laughter from my lung,

I would not fear the apple nor the flood

Nor the bad blood of spring.

Shall it be male or female? say the cells,

And drop the plum like fire from the flesh.

If I were tickled by the hatching hair,

The winging bone that sprouted in the heels,

The itch of man upon the baby’s thigh,

I would not fear the gallows nor the axe

Nor the crossed sticks of war.

Shall it be male or female? say the fingers

That chalk the walls with green girls and their men.

I would not fear the muscling-in of love

If I were tickled by the urchin hungers

Rehearsing heat upon a raw-edged nerve.

I would not fear the devil in the loin

Nor the outspoken grave.

If I were tickled by the lovers’ rub

That wipes away not crow’s-foot nor the lock

Of sick old manhood on the fallen jaws,

Time and the crabs and the sweethearting crib

Would leave me cold as butter for the flies,

The sea of scums could drown me as it broke

Dead on the sweethearts’ toes.

This world is half the

devil’s and my own,

Daft with the drug that’s smoking in a girl

And curling round the bud that forks her eye.

An old man’s shank one-marrowed with my bone,

And all the herrings smelling in the sea,

I sit and watch the worm beneath my nail

Wearing the quick away.

And that’s the rub, the only rub that

tickles.

1 comment