Revere rides his horse through Medford, Lexington, and Concord to warn the patriots.

The first edition

The original title page

The Wayside Inn, located in Sudbury, Massachusetts

CONTENTS

Introductory Note

PART FIRST.

Prelude I.

The Landlord’s Tale

Paul Revere’s Ride

The Landlord’s Tale: Interlude

The Student’s Tale

The Falcon of Ser Federigo

The Student’s Tale: Interlude

The Spanish Jew’s Tale

The Legend of Rabbi Ben Levi

The Spanish Jew’s Tale: Interlude

The Sicilian’s Tale

King Robert of Sicily

The Sicilian’s Tale: Interlude

The Musician’s Tale

The Saga of King Olaf

The Challenge of Thor

King Olaf’s Return

Thora of Rimol

Queen Sigrid the Haughty

The Skerry of Shrieks

The Wraith of Odin

Iron-Beard

Gudrun

Thangbrand the Priest

Raud the Strong

Bishop Sigurd of Salten Fiord

King Olaf’s Christmas

The Building of the Long Serpent

The Crew of the Long Serpent

A Little Bird in the Air

Queen Thyri and the Angelica Stalks

King Svend of the Forked Beard

King Olaf and Earl Sigvald

King Olaf’s War-Horns

Einar Tamberskelver

King Olaf’s Death-Drink

The Nun of Nidaros

The Musician’s Tale: Interlude

The Theologian’s Tale

Torquemada

The Theologian’s Tale: Interlude

The Poet’s Tale

The Birds of Killingworth

The Poet’s Tale: Finale

PART SECOND

Prelude II.

The Sicilian’s Tale

The Bell of Atri

The Sicilian’s Tale: Interlude

The Spanish Jew’s Tale

Kambalu

The Spanish Jew’s Tale: Interlude

The Student’s Tale

The Cobbler of Hagenau

The Student’s Tale: Interlude

The Musician’s Tale

The Ballad of Carmilhan

The Musician’s Tale : Interlude

The Poet’s Tale

Lady Wentworth

The Poet’s Tale: Interlude

The Theologian’s Tale

The Legend Beautiful

The Theologian’s Tale: Interlude

The Student’s Second Tale

The Baron of St. Castine

The Student’s Second Tale: Finale

PART THIRD.

Prelude III.

The Spanish Jew’s Tale

Azrael

The Spanish Jew’s Tale: Interlude

The Poet’s Tale

Charlemagne

The Poet’s Tale: Interlude

The Student’s Tale

Emma and Eginhard

The Student’s Tale: Interlude

The Theologian’s Tale

Elizabeth

The Theologian’s Tale: Interlude

The Sicilian’s Tale

The Monk of Casal-Maggiore

The Sicilian’s Tale: Interlude

The Spanish Jew’s Second Tale

Scanderbeg

The Spanish Jew’s Second Tale: Interlude

The Musician’s Tale

The Mother’s Ghost

The Musician’s Tale: Interlude

The Landlord’s Tale

The Rhyme of Sir Christopher

The Landlord’s Tale: Finale

Paul Revere (1734-1818) was a silversmith, early industrialist and a patriot in the American Revolution.

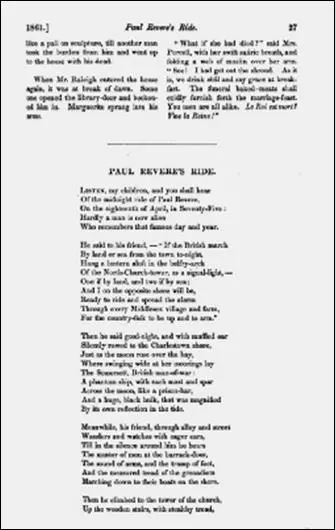

“Paul Revere’s Ride” in its first published form — The Atlantic Monthly in 1861.

The statue of Paul Revere in Boston, inspired by the poem, with the Old North Church in the background.

Introductory Note

THE PLAN for a group of stories under the fiction of a company of story-tellers at an inn appears to have visited Mr. Longfellow after he had made some progress with the separate tales. The considerable collection under the title of The Saga of King Olaf was indeed written at first with the design of independent publication. Nearly two years passed before he took up the task in earnest; then, in November, 1860, “with all kinds of interruptions,” he says, he wrote fifteen of the lyrics in as many days, and a few days afterward completed the whole of the Saga. Meanwhile he had written and published Paul Revere’s Ride, and before the publication of his volume he had printed one of the lyrics of the Saga and The Legend of Rabbi Ben Levi. Just when he determined upon the framework of The Wayside Inn does not appear; it is quite possible that he had connected The Saga of King Olaf, which had been lying by for two or three years, with his friend Ole Bull, and that the desire to use so picturesque a figure had suggested a group of which the musician should be one. Literature had notable precedents for the general plan of a company at an inn, but whether the actual inn at Sudbury came to localize his conception, or was itself the cause of the plan, is not quite clear.

He sent the book to the printer in April, 1863, under the title of The Sudbury Tales, but in August wrote to Mr. Fields: “I am afraid we have made a mistake in calling the new volume The Sudbury Tales. Now that I see it announced I do not like the title. Sumner cries out against it and has persuaded me, as I think he will you, to come back to The Wayside Inn. Pray think as we do.”

The book as originally planned consisted of the first part only, and was published November 25, 1863, in an edition of fifteen thousand copies, — an indication of the confidence which the publishers had in the poet’s popularity.

The disguises of characters were so slight that readers easily recognized most of them at once, and Mr. Longfellow himself never made any mystery of their identity. Just after the publication of the volume he wrote to a correspondent in England: —

“The Wayside Inn has more foundation in fact than you may suppose. The town of Sudbury is about twenty miles from Cambridge. Some two hundred years ago, an English family by the name of Howe built there a country house, which has remained in the family down to the present time, the last of the race dying but two years ago. Losing their fortune, they became inn-keepers; and for a century the Red-Horse Inn has flourished, going down from father to son. The place is just as I have described it, though no longer an inn. All this will account for the landlord’s coat-of-arms, and his being a justice of the peace, and his being known as ‘the Squire,’ — things that must sound strange in English ears. All the characters are real. The musician is Ole Bull; the Spanish Jew, Israel Edrehi, whom I have seen as I have painted him, etc., etc.”

It is easy to fill up the etc. of Mr. Longfellow’s catalogue. The poet is T. W. Parsons, the translator of Dante; the Sicilian, Luigi Monti, whose name occurs often in Mr. Longfellow’s Life as a familiar friend; the theologian, Professor Daniel Treadwell, a physicist of genius who had also a turn for theology; the student, Henry Ware Wales, a scholar of promise who had travelled much, who died early, and whose tastes appeared in the collection of books which he left to the library of Harvard College. This group was collected by the poet’s fancy; in point of fact three of them, Parsons, Monti, and Treadwell, were wont to spend their summer months at the inn.

The form was so agreeable that it was easy to extend it afterward so as to include the tales which the poet found it in his mind to write. The Second Day was published in 1872; The Third Part formed the principal portion of Aftermath in 1873, and subsequently the three parts were brought together, into a complete volume.

PART FIRST.

Prelude I.

ONE Autumn night, in Sudbury town,

Across the meadows bare and brown,

The windows of the wayside inn

Gleamed red with fire-light through the leaves

Of woodbine, hanging from the eaves 5

Their crimson curtains rent and thin.

As ancient is this hostelry

As any in the land may be,

Built in the old Colonial day,

When men lived in a grander way, 10

With ampler hospitality;

A kind of old Hobgoblin Hall,

Now somewhat fallen to decay,

With weather-stains upon the wall,

And stairways worn, and crazy doors, 15

And creaking and uneven floors,

And chimneys huge, and tiled and tall.

A region of repose it seems,

A place of slumber and of dreams,

Remote among the wooded hills! 20

For there no noisy railway speeds,

Its torch-race scattering smoke and gleeds;

But noon and night, the panting teams

Stop under the great oaks, that throw

Tangles of light and shade below, 25

On roofs and doors and window-sills.

Across the road the barns display

Their lines of stalls, their mows of hay,

Through the wide doors the breezes blow,

The wattled cocks strut to and fro, 30

And, half effaced by rain and shine,

The Red Horse prances on the sign.

Round this old-fashioned, quaint abode

Deep silence reigned, save when a gust

Went rushing down the county road, 35

And skeletons of leaves, and dust,

A moment quickened by its breath,

Shuddered and danced their dance of death,

And through the ancient oaks o’erhead

Mysterious voices moaned and fled. 40

But from the parlor of the inn

A pleasant murmur smote the ear,

Like water rushing through a weir:

Oft interrupted by the din

Of laughter and of loud applause, 45

And, in each intervening pause,

The music of a violin.

The fire-light, shedding over all

The splendor of its ruddy glow,

Filled the whole parlor large and low; 50

It gleamed on wainscot and on wall,

It touched with more than wonted grace

Fair Princess Mary’s pictured face;

It bronzed the rafters overhead,

On the old spinet’s ivory keys 55

It played inaudible melodies,

It crowned the sombre clock with flame,

The hands, the hours, the maker’s name,

And painted with a livelier red

The Landlord’s coat-of-arms again; 60

And, flashing on the window-pane,

Emblazoned with its light and shade

The jovial rhymes, that still remain,

Writ near a century ago,

By the great Major Molineaux, 65

Whom Hawthorne has immortal made.

Before the blazing fire of wood

Erect the rapt musician stood;

And ever and anon he bent

His head upon his instrument, 70

And seemed to listen, till he caught

Confessions of its secret thought, —

The joy, the triumph, the lament,

The exultation and the pain;

Then, by the magic of his art, 75

He soothed the throbbings of its heart,

And lulled it into peace again.

Around the fireside at their ease

There sat a group of friends, entranced

With the delicious melodies; 80

Who from the far-off noisy town

Had to the wayside inn come down,

To rest beneath its old oak trees.

The fire-light on their faces glanced,

Their shadows on the wainscot danced, 85

And, though of different lands and speech,

Each had his tale to tell, and each

Was anxious to be pleased and please.

And while the sweet musician plays,

Let me in outline sketch them all, 90

Perchance uncouthly as the blaze

With its uncertain touch portrays

Their shadowy semblance on the wall.

But first the Landlord will I trace;

Grave in his aspect and attire; 95

A man of ancient pedigree,

A Justice of the Peace was he,

Known in all Sudbury as “The Squire.”

Proud was he of his name and race,

Of old Sir William and Sir Hugh, 100

And in the parlor, full in view,

His coat-of-arms, well framed and glazed,

Upon the wall in colors blazed;

He beareth gules upon his shield,

A chevron argent in the field, 105

With three wolf’s-heads, and for the crest

A Wyvern part-per-pale addressed

Upon a helmet barred; below

The scroll reads, “By the name of Howe.”

And over this, no longer bright, 110

Though glimmering with a latent light,

Was hung the sword his grandsire bore

In the rebellious days of yore,

Down there at Concord in the fight.

A youth was there, of quiet ways, 115

A Student of old books and days,

To whom all tongues and lands were known,

And yet a lover of his own;

With many a social virtue graced,

And yet a friend of solitude; 120

A man of such a genial mood

The heart of all things he embraced,

And yet of such fastidious taste,

He never found the best too good.

Books were his passion and delight, 125

And in his upper room at home

Stood many a rare and sumptuous tome,

In vellum bound, with gold bedight,

Great volumes garmented in white,

Recalling Florence, Pisa, Rome. 130

He loved the twilight that surrounds

The border-land of old romance;

Where glitter hauberk, helm, and lance,

And banner waves, and trumpet sounds,

And ladies ride with hawk on wrist, 135

And mighty warriors sweep along,

Magnified by the purple mist,

The dusk of centuries and of song.

The chronicles of Charlemagne,

Of Merlin and the Mort d’Arthure, 140

Mingled together in his brain

With tales of Flores and Blanchefleur,

Sir Ferumbras, Sir Eglamour,

Sir Launcelot, Sir Morgadour,

Sir Guy, Sir Bevis, Sir Gawain. 145

A young Sicilian, too, was there;

In sight of Etna born and bred,

Some breath of its volcanic air

Was glowing in his heart and brain,

And, being rebellious to his liege, 150

After Palermo’s fatal siege,

Across the western seas he fled,

In good King Bomba’s happy reign.

His face was like a summer night,

All flooded with a dusky light; 155

His hands were small; his teeth shone white

As sea-shells, when he smiled or spoke;

His sinews supple and strong as oak;

Clean shaven was he as a priest,

Who at the mass on Sunday sings, 160

Save that upon his upper lip

His beard, a good palm’s length at least,

Level and pointed at the tip,

Shot sideways, like a swallow’s wings.

The poets read he o’er and o’er, 165

And most of all the Immortal Four

Of Italy; and next to those,

The story-telling bard of prose,

Who wrote the joyous Tuscan tales

Of the Decameron, that make 170

Fiesole’s green hills and vales

Remembered for Boccaccio’s sake.

Much too of music was his thought;

The melodies and measures fraught

With sunshine and the open air, 175

Of vineyards and the singing sea

Of his beloved Sicily;

And much it pleased him to peruse

The songs of the Sicilian muse, —

Bucolic songs by Meli sung 180

In the familiar peasant tongue,

That made men say, “Behold! once more

The pitying gods to earth restore

Theocritus of Syracuse!”

A Spanish Jew from Alicant 185

With aspect grand and grave was there;

Vender of silks and fabrics rare,

And attar of rose from the Levant.

Like an old Patriarch he appeared,

Abraham or Isaac, or at least 190

Some later Prophet or High-Priest;

With lustrous eyes, and olive skin,

And, wildly tossed from cheeks and chin,

The tumbling cataract of his beard.

His garments breathed a spicy scent 195

Of cinnamon and sandal blent,

Like the soft aromatic gales

That meet the mariner, who sails

Through the Moluccas, and the seas

That wash the shores of Celebes. 200

All stories that recorded are

By Pierre Alphonse he knew by heart,

And it was rumored he could say

The Parables of Sandabar,

And all the Fables of Pilpay, 205

Or if not all, the greater part!

Well versed was he in Hebrew books,

Talmud and Targum, and the lore

Of Kabala; and evermore

There was a mystery in his looks; 210

His eyes seemed gazing far away,

As if in vision or in trance

He heard the solemn sackbut play,

And saw the Jewish maidens dance.

A Theologian, from the school 215

Of Cambridge on the Charles, was there;

Skilful alike with tongue and pen,

He preached to all men everywhere

The Gospel of the Golden Rule,

The New Commandment given to men, 220

Thinking the deed, and not the creed,

Would help us in our utmost need.

With reverent feet the earth he trod,

Nor banished nature from his plan,

But studied still with deep research 225

To build the Universal Church,

Lofty as is the love of God,

And ample as the wants of man.

A Poet, too, was there, whose verse

Was tender, musical, and terse; 230

The inspiration, the delight,

The gleam, the glory, the swift flight

Of thoughts so sudden, that they seem

The revelations of a dream,

All these were his; but with them came 235

No envy of another’s fame;

He did not find his sleep less sweet,

For music in some neighboring street

Nor rustling hear in every breeze

The laurels of Miltiades. 240

Honor and blessings on his head

While living, good report when dead,

Who, not too eager for renown,

Accepts, but does not clutch, the crown!

Last the Musician, as he stood 245

Illumined by that fire of wood;

Fair-haired, blue-eyed, his aspect blithe,

His figure tall and straight and lithe,

And every feature of his face

Revealing his Norwegian race; 250

A radiance, streaming from within,

Around his eyes and forehead beamed,

The Angel with the violin,

Painted by Raphael, he seemed.

He lived in that ideal world 255

Whose language is not speech, but song;

Around him evermore the throng

Of elves and sprites their dances whirled;

The Strömkarl sang, the cataract hurled

Its headlong waters from the height; 260

And mingled in the wild delight

The scream of sea-birds in their flight,

The rumor of the forest trees,

The plunge of the implacable seas,

The tumult of the wind at night, 265

Voices of eld, like trumpets blowing,

Old ballads, and wild melodies

Through mist and darkness pouring forth,

Like Elivagar’s river flowing

Out of the glaciers of the North. 270

The instrument on which he played

Was in Cremona’s workshops made,

By a great master of the past,

Ere yet was lost the art divine;

Fashioned of maple and of pine, 275

That in Tyrolean forests vast

Had rocked and wrestled with the blast:

Exquisite was it in design,

Perfect in each minutest part,

A marvel of the lutist’s art; 280

And in its hollow chamber, thus,

The maker from whose hands it came

Had written his unrivalled name, —

“Antonius Stradivarius.”

And when he played, the atmosphere 285

Was filled with magic, and the ear

Caught echoes of that Harp of Gold,

Whose music had so weird a sound,

The hunted stag forgot to bound,

The leaping rivulet backward rolled, 290

The birds came down from bush and tree,

The dead came from beneath the sea,

The maiden to the harper’s knee!

The music ceased; the applause was loud,

The pleased musician smiled and bowed; 295

The wood-fire clapped its hands of flame,

The shadows on the wainscot stirred,

And from the harpsichord there came

A ghostly murmur of acclaim,

A sound like that sent down at night 300

By birds of passage in their flight,

From the remotest distance heard.

Then silence followed; then began

A clamor for the Landlord’s tale, —

The story promised them of old, 305

They said, but always left untold;

And he, although a bashful man,

And all his courage seemed to fail,

Finding excuse of no avail,

Yielded; and thus the story ran. 310

The Landlord’s Tale

Paul Revere’s Ride

LISTEN, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year. 5

He said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light, —

One, if by land, and two, if by sea; 10

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm.”

Then he said, “Good night!” and with muffled oar 15

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war;

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar 20

Across the moon like a prison bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.

Meanwhile, his friend, through alley and street,

Wanders and watches with eager ears, 25

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers,

Marching down to their boats on the shore. 30

Then he climbed the tower of the Old North Church,

By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread,

To the belfry-chamber overhead,

And startled the pigeons from their perch

On the sombre rafters, that round him made 35

Masses and moving shapes of shade, —

By the trembling ladder, steep and tall,

To the highest window in the wall,

Where he paused to listen and look down

A moment on the roofs of the town, 40

And the moonlight flowing over all.

Beneath, in the churchyard, lay the dead,

In their night-encampment on the hill,

Wrapped in silence so deep and still

That he could hear, like a sentinel’s tread, 45

The watchful night-wind, as it went

Creeping along from tent to tent,

And seeming to whisper, “All is well!”

A moment only he feels the spell

Of the place and the hour, and the secret dread 50

Of the lonely belfry and the dead;

For suddenly all his thoughts are bent

On a shadowy something far away,

Where the river widens to meet the bay, —

A line of black that bends and floats 55

On the rising tide, like a bridge of boats.

Meanwhile, impatient to mount and ride,

Booted and spurred, with a heavy stride

On the opposite shore walked Paul Revere.

Now he patted his horse’s side, 60

Now gazed at the landscape far and near,

Then, impetuous, stamped the earth,

And turned and tightened his saddle-girth;

But mostly he watched with eager search

The belfry-tower of the Old North Church, 65

As it rose above the graves on the hill,

Lonely and spectral and sombre and still.

And lo! as he looks, on the belfry’s height

A glimmer, and then a gleam of light!

He springs to the saddle, the bridle he turns, 70

But lingers and gazes, till full on his sight

A second lamp in the belfry burns!

A hurry of hoofs in a village street,

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark 75

Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet:

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light.

The fate of a nation was riding that night;

And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight,

Kindled the land into flame with its heat. 80

He has left the village and mounted the steep,

And beneath him, tranquil and broad and deep,

Is the Mystic, meeting the ocean tides;

And under the alders that skirt its edge,

Now soft on the sand, now loud on the ledge, 85

Is heard the tramp of his steed as he rides.

It was twelve by the village clock,

When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.

He heard the crowing of the cock,

And the barking of the farmer’s dog, 90

And felt the damp of the river fog,

That rises after the sun goes down.

It was one by the village clock,

When he galloped into Lexington.

He saw the gilded weathercock 95

Swim in the moonlight as he passed,

And the meeting-house windows, blank and bare,

Gaze at him with a spectral glare,

As if they already stood aghast

At the bloody work they would look upon. 100

It was two by the village clock,

When he came to the bridge in Concord town.

He heard the bleating of the flock,

And the twitter of birds among the trees,

And felt the breath of the morning breeze 105

Blowing over the meadows brown.

And one was safe and asleep in his bed

Who at the bridge would be first to fall,

Who that day would be lying dead,

Pierced by a British musket-ball. 110

You know the rest. In the books you have read,

How the British Regulars fired and fled, —

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farm-yard wall,

Chasing the red-coats down the lane, 115

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm 120

To every Middlesex village and farm, —

A cry of defiance and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past, 125

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere. 130

The Landlord’s Tale: Interlude

THE LANDLORD ended thus his tale,

Then rising took down from its nail

The sword that hung there, dim with dust,

And cleaving to its sheath with rust,

And said, “This sword was in the fight.” 5

The Poet seized it, and exclaimed,

“It is the sword of a good knight,

Though homespun was his coat-of-mail;

What matter if it be not named

Joyeuse, Colada, Durindale, 10

Excalibar, or Aroundight,

Or other name the books record?

Your ancestor, who bore this sword

As Colonel of the Volunteers,

Mounted upon his old gray mare, 15

Seen here and there and everywhere,

To me a grander shape appears

Than old Sir William, or what not,

Clinking about in foreign lands

With iron gauntlets on his hands, 20

And on his head an iron pot!”

All laughed; the Landlord’s face grew red

As his escutcheon on the wall;

He could not comprehend at all

The drift of what the Poet said; 25

For those who had been longest dead

Were always greatest in his eyes;

And he was speechless with surprise

To see Sir William’s plumèd head

Brought to a level with the rest, 30

And made the subject of a jest.

And this perceiving, to appease

The Landlord’s wrath, the others’ fears,

The Student said, with careless ease,

“The ladies and the cavaliers, 35

The arms, the loves, the courtesies,

The deeds of high emprise, I sing!

Thus Ariosto says, in words

That have the stately stride and ring

Of armèd knights and clashing swords. 40

Now listen to the tale I bring;

Listen! though not to me belong

The flowing draperies of his song,

The words that rouse, the voice that charms.

The Landlord’s tale was one of arms, 45

Only a tale of love is mine,

Blending the human and divine,

A tale of the Decameron, told

In Palmieri’s garden old,

By Fiametta, laurel-crowned, 50

While her companions lay around,

And heard the intermingled sound

Of airs that on their errands sped,

And wild birds gossiping overhead,

And lisp of leaves, and fountain’s fall, 55

And her own voice more sweet than all,

Telling the tale, which, wanting these,

Perchance may lose its power to please.”

The Student’s Tale

The Falcon of Ser Federigo

ONE summer morning, when the sun was hot,

Weary with labor in his garden-plot,

On a rude bench beneath his cottage eaves,

Ser Federigo sat among the leaves

Of a huge vine, that, with its arms outspread, 5

Hung its delicious clusters overhead.

Below him, through the lovely valley, flowed

The river Arno, like a winding road,

And from its banks were lifted high in air

The spires and roofs of Florence called the Fair; 10

To him a marble tomb, that rose above

His wasted fortunes and his buried love.

For there, in banquet and in tournament,

His wealth had lavished been, his substance spent,

To woo and lose, since ill his wooing sped, 15

Monna Giovanna, who his rival wed,

Yet ever in his fancy reigned supreme,

The ideal woman of a young man’s dream.

Then he withdrew, in poverty and pain,

To this small farm, the last of his domain, 20

His only comfort and his only care

To prune his vines, and plant the fig and pear;

His only forester and only guest

His falcon, faithful to him, when the rest,

Whose willing hands had found so light of yore 25

The brazen knocker of his palace door,

Had now no strength to lift the wooden latch,

That entrance gave beneath a roof of thatch.

Companion of his solitary ways,

Purveyor of his feasts on holidays, 30

On him this melancholy man bestowed

The love with which his nature overflowed.

And so the empty-handed years went round,

Vacant, though voiceful with prophetic sound,

And so, that summer morn, he sat and mused 35

With folded, patient hands, as he was used,

And dreamily before his half-closed sight

Floated the vision of his lost delight.

Beside him, motionless, the drowsy bird

Dreamed of the chase, and in his slumber heard 40

The sudden, scythe-like sweep of wings, that dare

The headlong plunge through eddying gulfs of air,

Then, starting broad awake upon his perch,

Tinkled his bells, like mass-bells in a church,

And looking at his master, seemed to say, 45

“Ser Federigo, shall we hunt to-day?”

Ser Federigo thought not of the chase;

The tender vision of her lovely face,

I will not say he seems to see, he sees

In the leaf-shadows of the trellises, 50

Herself, yet not herself; a lovely child

With flowing tresses, and eyes wide and wild,

Coming undaunted up the garden walk,

And looking not at him, but at the hawk.

“Beautiful falcon!” said he, “would that I 55

Might hold thee on my wrist, or see thee fly!”

The voice was hers, and made strange echoes start

Through all the haunted chambers of his heart,

As an æolian harp through gusty doors

Of some old ruin its wild music pours. 60

“Who is thy mother, my fair boy?” he said,

His hand laid softly on that shining head.

“Monna Giovanna. Will you let me stay

A little while, and with your falcon play?

We live there, just beyond your garden wall, 65

In the great house behind the poplars tall.”

So he spake on; and Federigo heard

As from afar each softly uttered word,

And drifted onward through the golden gleams

And shadows of the misty sea of dreams, 70

As mariners becalmed through vapors drift,

And feel the sea beneath them sink and lift,

And hear far off the mournful breakers roar,

And voices calling faintly from the shore!

Then waking from his pleasant reveries, 75

He took the little boy upon his knees,

And told him stories of his gallant bird,

Till in their friendship he became a third.

Monna Giovanna, widowed in her prime,

Had come with friends to pass the summer time 80

In her grand villa, half-way up the hill,

O’erlooking Florence, but retired and still;

With iron gates, that opened through long lines

Of sacred ilex and centennial pines,

And terraced gardens, and broad steps of stone, 85

And sylvan deities, with moss o’ergrown.

And fountains palpitating in the heat,

And all Val d’Arno stretched beneath its feet.

Here in seclusion, as a widow may,

The lovely lady whiled the hours away, 90

Pacing in sable robes the statued hall,

Herself the stateliest statue among all,

And seeing more and more, with secret joy,

Her husband risen and living in her boy,

Till the lost sense of life returned again, 95

Not as delight, but as relief from pain.

Meanwhile the boy, rejoicing in his strength,

Stormed down the terraces from length to length;

The screaming peacock chased in hot pursuit,

And climbed the garden trellises for fruit. 100

But his chief pastime was to watch the flight,

Of a gerfalcon, soaring into sight,

Beyond the trees that fringed the garden wall,

Then downward stooping at some distant call;

And as he gazed full often wondered he 105

Who might the master of the falcon be,

Until that happy morning, when he found

Master and falcon in the cottage ground.

And now a shadow and a terror fell

On the great house, as if a passing-bell 110

Tolled from the tower, and filled each spacious room

With secret awe and preternatural gloom;

The petted boy grew ill, and day by day

Pined with mysterious malady away.

The mother’s heart would not be comforted; 115

Her darling seemed to her already dead,

And often, sitting by the sufferer’s side,

“What can I do to comfort thee?” she cried.

At first the silent lips made no reply,

But, moved at length by her importunate cry, 120

“Give me,” he answered, with imploring tone,

“Ser Federigo’s falcon for my own!”

No answer could the astonished mother make;

How could she ask, e’en for her darling’s sake,

Such favor at a luckless lover’s hand, 125

Well knowing that to ask was to command?

Well knowing, what all falconers confessed,

In all the land that falcon was the best,

The master’s pride and passion and delight,

And the sole pursuivant of this poor knight. 130

But yet, for her child’s sake, she could no less

Than give assent, to soothe his restlessness,

So promised, and then promising to keep

Her promise sacred, saw him fall asleep.

The morrow was a bright September morn; 135

The earth was beautiful as if new-born;

There was that nameless splendor everywhere,

That wild exhilaration in the air,

Which makes the passers in the city street

Congratulate each other as they meet. 140

Two lovely ladies, clothed in cloak and hood,

Passed through the garden gate into the wood,

Under the lustrous leaves, and through the sheen

Of dewy sunshine showering down between.

The one, close-hooded, had the attractive grace 145

Which sorrow sometimes lends a woman’s face;

Her dark eyes moistened with the mists that roll

From the gulf-stream of passion in the soul;

The other with her hood thrown back, her hair

Making a golden glory in the air, 150

Her cheeks suffused with an auroral blush,

Her young heart singing louder than the thrush,

So walked, that morn, through mingled light and shade,

Each by the other’s presence lovelier made,

Monna Giovanna and her bosom friend, 155

Intent upon their errand and its end.

They found Ser Federigo at his toil,

Like banished Adam, delving in the soil;

And when he looked and these fair women spied,

The garden suddenly was glorified; 160

His long-lost Eden was restored again,

And the strange river winding through the plain

No longer was the Arno to his eyes,

But the Euphrates watering Paradise!

Monna Giovanna raised her stately head, 165

And with fair words of salutation said:

“Ser Federigo, we come here as friends,

Hoping in this to make some poor amends

For past unkindness. I who ne’er before

Would even cross the threshold of your door, 170

I who in happier days such pride maintained,

Refused your banquets, and your gifts disdained,

This morning come, a self-invited guest,

To put your generous nature to the test,

And breakfast with you under your own vine.” 175

To which he answered: “Poor desert of mine,

Not your unkindness call it, for if aught

Is good in me of feeling or of thought,

From you it comes, and this last grace outweighs

All sorrows, all regrets of other days.” 180

And after further compliment and talk,

Among the asters in the garden walk

He left his guests; and to his cottage turned,

And as he entered for a moment yearned

For the lost splendors of the days of old, 185

The ruby glass, the silver and the gold,

And felt how piercing is the sting of pride,

By want embittered and intensified.

He looked about him for some means or way

To keep this unexpected holiday; 190

Searched every cupboard, and then searched again,

Summoned the maid, who came, but came in vain;

“The Signor did not hunt to-day,” she said,

“There’s nothing in the house but wine and bread.”

Then suddenly the drowsy falcon shook 195

His little bells, with that sagacious look,

Which said, as plain as language to the ear,

“If anything is wanting, I am here!”

Yes, everything is wanting, gallant bird!

The master seized thee without further word. 200

Like thine own lure, he whirled thee round; ah me!

The pomp and flutter of brave falconry,

The bells, the jesses, the bright scarlet hood,

The flight and the pursuit o’er field and wood,

All these forevermore are ended now; 205

No longer victor, but the victim thou!

Then on the board a snow-white cloth he spread,

Laid on its wooden dish the loaf of bread,

Brought purple grapes with autumn sunshine hot,

The fragrant peach, the juicy bergamot; 210

Then in the midst a flask of wine he placed

And with autumnal flowers the banquet graced.

Ser Federigo, would not these suffice

Without thy falcon stuffed with cloves and spice?

When all was ready, and the courtly dame 215

With her companion to the cottage came,

Upon Ser Federigo’s brain there fell

The wild enchantment of a magic spell!

The room they entered, mean and low and small,

Was changed into a sumptuous banquet hall, 220

With fanfares by aerial trumpets blown;

The rustic chair she sat on was a throne;

He ate celestial food, and a divine

Flavor was given to his country wine,

And the poor falcon, fragrant with his spice, 225

A peacock was, or bird of paradise!

When the repast was ended, they arose

And passed again into the garden-close.

Then said the lady, “Far too well I know,

Remembering still the days of long ago, 230

Though you betray it not, with what surprise

You see me here in this familiar wise.

You have no children, and you cannot guess

What anguish, what unspeakable distress

A mother feels, whose child is lying ill, 235

Nor how her heart anticipates his will.

And yet for this, you see me lay aside

All womanly reserve and check of pride,

And ask the thing most precious in your sight,

Your falcon, your sole comfort and delight, 240

Which if you find it in your heart to give,

My poor, unhappy boy perchance may live.”

Ser Federigo listens, and replies,

With tears of love and pity in his eyes:

“Alas, dear lady! there can be no task 245

So sweet to me, as giving when you ask.

One little hour ago, if I had known

This wish of yours, it would have been my own.

But thinking in what manner I could best

Do honor to the presence of my guest, 250

I deemed that nothing worthier could be

Than what most dear and precious was to me;

And so my gallant falcon breathed his last

To furnish forth this morning our repast.”

In mute contrition, mingled with dismay, 255

The gentle lady turned her eyes away,

Grieving that he such sacrifice should make

And kill his falcon for a woman’s sake,

Yet feeling in her heart a woman’s pride,

That nothing she could ask for was denied; 260

Then took her leave, and passed out at the gate

With footstep slow and soul disconsolate.

Three days went by, and lo! a passing-bell

Tolled from the little chapel in the dell;

Ten strokes Ser Federigo heard, and said, 265

Breathing a prayer, “Alas! her child is dead!”

Three months went by; and lo! a merrier chime

Rang from the chapel bells at Christmas-time;

The cottage was deserted, and no more

Ser Federigo sat beside its door, 270

But now, with servitors to do his will,

In the grand villa, half-way up the hill,

Sat at the Christmas feast, and at his side

Monna Giovanna, his beloved bride,

Never so beautiful, so kind, so fair, 275

Enthroned once more in the old rustic chair,

High-perched upon the back of which there stood

The image of a falcon carved in wood,

And underneath the inscription, with a date,

“All things come round to him who will but wait.” 280

The Student’s Tale: Interlude

SOON as the story reached its end,

One, over eager to commend,

Crowned it with injudicious praise;

And then the voice of blame found vent,

And fanned the embers of dissent 5

Into a somewhat lively blaze.

The Theologian shook his head;

“These old Italian tales,” he said,

“From the much-praised Decameron down

Through all the rabble of the rest, 10

Are either trifling, dull, or lewd;

The gossip of a neighborhood

In some remote provincial town,

A scandalous chronicle at best!

They seem to me a stagnant fen, 15

Grown rank with rushes and with reeds,

Where a white lily, now and then,

Blooms in the midst of noxious weeds

And deadly nightshade on its banks!”

To this the Student straight replied, 20

“For the white lily, many thanks!

One should not say, with too much pride,

Fountain, I will not drink of thee!

Nor were it grateful to forget

That from these reservoirs and tanks 25

Even imperial Shakespeare drew

His Moor of Venice, and the Jew,

And Romeo and Juliet,

And many a famous comedy.”

Then a long pause; till some one said, 30

“An Angel is flying overhead!”

At these words spake the Spanish Jew,

And murmured with an inward breath:

“God grant, if what you say be true,

It may not be the Angel of Death!” 35

And then another pause; and then,

Stroking his beard, he said again:

“This brings back to my memory

A story in the Talmud told,

That book of gems, that book of gold, 40

Of wonders many and manifold,

A tale that often comes to me,

And fills my heart, and haunts my brain,

And never wearies nor grows old.”

The Spanish Jew’s Tale

The Legend of Rabbi Ben Levi

RABBI BEN LEVI, on the Sabbath, read

A volume of the Law, in which it said,

“No man shall look upon my face and live.”

And as he read, he prayed that God would give

His faithful servant grace with mortal eye 5

To look upon His face and yet not die.

Then fell a sudden shadow on the page,

And, lifting up his eyes, grown dim with age,

He saw the Angel of Death before him stand,

Holding a naked sword in his right hand. 10

Rabbi Ben Levi was a righteous man,

Yet through his veins a chill of terror ran.

With trembling voice he said, “What wilt thou here?”

The Angel answered, “Lo! the time draws near

When thou must die; yet first, by God’s decree, 15

Whate’er thou askest shall be granted thee.”

Replied the Rabbi, “Let these living eyes

First look upon my place in Paradise.”

Then said the Angel, “Come with me and look.”

Rabbi Ben Levi closed the sacred book, 20

And rising, and uplifting his gray head,

“Give me thy sword,” he to the Angel said,

“Lest thou shouldst fall upon me by the way.”

The Angel smiled and hastened to obey,

Then led him forth to the Celestial Town, 25

And set him on the wall, whence, gazing down,

Rabbi Ben Levi, with his living eyes,

Might look upon his place in Paradise.

Then straight into the city of the Lord

The Rabbi leaped with the Death-Angel’s sword, 30

And through the streets there swept a sudden breath

Of something there unknown, which men call death.

Meanwhile the Angel stayed without, and cried,

“Come back!” To which the Rabbi’s voice replied,

“No! in the name of God, whom I adore, 35

I swear that hence I will depart no more!”

Then all the Angels cried, “O Holy One,

See what the son of Levi here hath done!

The kingdom of Heaven he takes by violence,

And in Thy name refuses to go hence!” 40

The Lord replied, “My Angels, be not wroth;

Did e’er the son of Levi break his oath?

Let him remain; for he with mortal eye

Shall look upon my face and yet not die.”

Beyond the outer wall the Angel of Death 45

Heard the great voice, and said, with panting breath,

“Give back the sword, and let me go my way.”

Whereat the Rabbi paused, and answered, “Nay!

Anguish enough already hath it caused

Among the sons of men.” And while he paused 50

He heard the awful mandate of the Lord

Resounding through the air, “Give back the sword!”

The Rabbi bowed his head in silent prayer,

Then said he to the dreadful Angel, “Swear

No human eye shall look on it again; 55

But when thou takest away the souls of men,

Thyself unseen, and with an unseen sword,

Thou wilt perform the bidding of the Lord.”

The Angel took the sword again, and swore,

And walks on earth unseen forevermore. 60

The Spanish Jew’s Tale: Interlude

HE ended: and a kind of spell

Upon the silent listeners fell.

His solemn manner and his words

Had touched the deep, mysterious chords

That vibrate in each human breast 5

Alike, but not alike confessed.

The spiritual world seemed near;

And close above them, full of fear,

Its awful adumbration passed,

A luminous shadow, vague and vast. 10

They almost feared to look, lest there,

Embodied from the impalpable air,

They might behold the Angel stand,

Holding the sword in his right hand.

At last, but in a voice subdued, 15

Not to disturb their dreamy mood,

Said the sicilian: “While you spoke,

Telling your legend marvellous,

Suddenly in my memory woke

The thought of one, now gone from us, — 20

An old Abate, meek and mild,

My friend and teacher, when a child,

Who sometimes in those days of old

The legend of an Angel told,

Which ran, as I remember thus.” 25

The Sicilian’s Tale

King Robert of Sicily

ROBERT of Sicily, brother of Pope Urbane

And Valmond, Emperor of Allemaine,

Apparelled in magnificent attire,

With retinue of many a knight and squire,

On St. John’s eve, at vespers, proudly sat 5

And heard the priests chant the Magnificat.

And as he listened, o’er and o’er again

Repeated, like a burden or refrain,

He caught the words, “Deposuit potentes

De sede, et exaltavit humiles;” 10

And slowly lifting up his kingly head

He to a learned clerk beside him said,

“What mean these words?” The clerk made answer meet,

“He has put down the mighty from their seat,

And has exalted them of low degree.” 15

Thereat King Robert muttered scornfully,

“‘T is well that such seditious words are sung

Only by priests and in the Latin tongue;

For unto priests and people be it known,

There is no power can push me from my throne!” 20

And leaning back, he yawned and fell asleep,

Lulled by the chant monotonous and deep.

When he awoke, it was already night;

The church was empty, and there was no light,

Save where the lamps, that glimmered few and faint, 25

Lighted a little space before some saint.

He started from his seat and gazed around,

But saw no living thing and heard no sound.

He groped towards the door, but it was locked;

He cried aloud, and listened, and then knocked, 30

And uttered awful threatenings and complaints,

And imprecations upon men and saints.

The sounds reëchoed from the roof and walls

As if dead priests were laughing in their stalls.

At length the sexton, hearing from without 35

The tumult of the knocking and the shout,

And thinking thieves were in the house of prayer,

Came with his lantern, asking, “Who is there?”

Half choked with rage, King Robert fiercely said,

“Open: ‘t is I, the King! Art thou afraid?” 40

The frightened sexton, muttering, with a curse,

“This is some drunken vagabond, or worse!”

Turned the great key and flung the portal wide;

A man rushed by him at a single stride,

Haggard, half naked, without hat or cloak, 45

Who neither turned, nor looked at him, nor spoke,

But leaped into the blackness of the night,

And vanished like a spectre from his sight.

Robert of Sicily, brother of Pope Urbane

And Valmond, Emperor of Allemaine, 50

Despoiled of his magnificent attire,

Bareheaded, breathless, and besprent with mire,

With sense of wrong and outrage desperate,

Strode on and thundered at the palace gate;

Rushed through the courtyard, thrusting in his rage 55

To right and left each seneschal and page,

And hurried up the broad and sounding stair,

His white face ghastly in the torches’ glare.

From hall to hall he passed with breathless speed;

Voices and cries he heard, but did not heed, 60

Until at last he reached the banquet-room,

Blazing with light, and breathing with perfume.

There on the dais sat another king,

Wearing his robes, his crown, his signet-ring,

King Robert’s self in features, form, and height, 65

But all transfigured with angelic light!

It was an Angel; and his presence there

With a divine effulgence filled the air,

An exaltation, piercing the disguise,

Though none the hidden Angel recognize. 70

A moment speechless, motionless, amazed,

The throneless monarch on the Angel gazed,

Who met his look of anger and surprise

With the divine compassion of his eyes;

Then said, “Who art thou? and why com’st thou here?” 75

To which King Robert answered with a sneer,

“I am the King, and come to claim my own

From an impostor, who usurps my throne!”

And suddenly, at these audacious words,

Up sprang the angry guests, and drew their swords; 80

The Angel answered, with unruffled brow,

“Nay, not the King, but the King’s Jester, thou

Henceforth shalt wear the bells and scalloped cape,

And for thy counsellor shalt lead an ape;

Thou shalt obey my servants when they call, 85

And wait upon my henchmen in the hall!”

Deaf to King Robert’s threats and cries and prayers,

They thrust him from the hall and down the stairs;

A group of tittering pages ran before,

And as they opened wide the folding-door, 90

His heart failed, for he heard, with strange alarms,

The boisterous laughter of the men-at-arms,

And all the vaulted chamber roar and ring

With the mock plaudits of “Long live the King!”

Next morning, waking with the day’s first beam, 95

He said within himself, “It was a dream!”

But the straw rustled as he turned his head,

There were the cap and bells beside his bed,

Around him rose the bare, discolored walls,

Close by, the steeds were champing in their stalls, 100

And in the corner, a revolting shape,

Shivering and chattering sat the wretched ape.

It was no dream; the world he loved so much

Had turned to dust and ashes at his touch!

Days came and went; and now returned again 105

To Sicily the old Saturnian reign;

Under the Angel’s governance benign

The happy island danced with corn and wine,

And deep within the mountain’s burning breast

Enceladus, the giant, was at rest. 110

Meanwhile King Robert yielded to his fate,

Sullen and silent and disconsolate.

Dressed in the motley garb that Jesters wear,

With look bewildered and a vacant stare,

Close shaven above the ears, as monks are shorn, 115

By courtiers mocked, by pages laughed to scorn,

His only friend the ape, his only food

What others left, — he still was unsubdued.

And when the Angel met him on his way,

And half in earnest, half in jest, would say, 120

Sternly, though tenderly, that he might feel

The velvet scabbard held a sword of steel,

“Art thou the King?” the passion of his woe

Burst from him in resistless overflow,

And, lifting high his forehead, he would fling 125

The haughty answer back, “I am, I am the King!”

Almost three years were ended; when there came

Ambassaders of great repute and name

From Valmond, Emperor of Allemaine,

Unto King Robert, saying that Pope Urbane 130

By letter summoned them forthwith to come

On Holy Thursday to his city of Rome.

The Angel with great joy received his guests,

And gave them presents of embroidered vests,

And velvet mantles with rich ermine lined, 135

And rings and jewels of the rarest kind.

Then he departed with them o’er the sea

Into the lovely land of Italy,

Whose loveliness was more resplendent hade

By the mere passing of that cavalcade, 140

With Pumes, and cloaks, and housings, and the stir

Of jewelled bridle and of golden spur.

And lo among the menials, in mock state,

Upon a piebald steed, with shambling gait,

His look of fox-tails flapping in the wind, 145

The solemn ape demurely perched behind,

King Robert rode, making huge merriment

In all the country towns through which they went.

The Pope received them with great pomp and blare

Of bannered trumpets, on Saint Peter’s square, 150

Giving his benediction and embrace,

Fervent, and full of apostolic grace.

While with congratulations and with prayers

He entertained the Angel unawares,

Robert, the Jester, bursting through the crowd, 155

Into their presence rushed, and cried aloud,

“I am the King! Look, and behold in me

Robert, your brother, King of Sicily!

This man, who wears my semblance to your eyes,

Is an impostor in a king’s disguise. 160

Do you not know me? does no voice within

Answer my cry, and say we are akin?”

The Pope in silence, but with troubled mien,

Gazed at the Angel’s countenance serene;

The Emperor, laughing, said, “It is strange sport 165

To keep a madman for thy Fool at court!”

And the poor, baffled Jester in disgrace

Was hustled back among the populace.

In solemn state the Holy Week went by,

And Easter Sunday gleamed upon the sky; 170

The presence of the Angel, with its light,

Before the sun rose, made the city bright,

And with new fervor filled the hearts of men,

Who felt that Christ indeed had risen again.

Even the Jester, on his bed of straw, 175

With haggard eyes the unwonted splendor saw,

He felt within a power unfelt before,

And, kneeling humbly on his chamber floor,

He heard the rushing garments of the Lord

Sweep through the silent air, ascending heavenward. 180

And now the visit ending, and once more

Valmond returning to the Danube’s shore,

Homeward the Angel journeyed, and again

The land was made resplendent with his train,

Flashing along the towns of Italy 185

Unto Salerno, and from thence by sea.

And when once more within Palermo’s wall,

And, seated on the throne in his great hall,

He heard the Angelus from convent towers,

As if the better world conversed with ours, 190

He beckoned to King Robert to draw nigher,

And with a gesture bade the rest retire;

And when they were alone, the Angel said,

“Art thou the King?” Then, bowing down his head,

King Robert crossed both hands upon his breast, 195

And meekly answered him: “Thou knowest best!

My sins as scarlet are; let me go hence,

And in some cloister’s school of penitence,

Across those stones, that pave the way to heaven,

Walk barefoot, till my guilty soul be shriven!” 200

The Angel smiled, and from his radiant face

A holy light illumined all the place,

And through the open window, loud and clear,

They heard the monks chant in the chapel near,

Above the stir and tumult of the street: 205

“He has put down the mighty from their seat,

And has exalted them of low degree!”

And through the chant a second melody

Rose like the throbbing of a single string:

“I am an Angel, and thou art the King!” 210

King Robert, who was standing near the throne,

Lifted his eyes, and lo! he was alone!

But all apparelled as in days of old,

With ermined mantle and with cloth of gold;

And when his courtiers came, they found him there

215

Kneeling upon the floor, absorbed in silent prayer.

The Sicilian’s Tale: Interlude

AND then the blue-eyed Norseman told

A Saga of the days of old.

“There is,” said he, “a wondrous book

Of Legends in the old Norse tongue,

Of the dead kings of Norroway, — 5

Legends that once were told or sung

In many a smoky fireside nook

Of Iceland, in the ancient day,

By wandering Saga-man or Scald;

‘Heimskringla’ is the volume called; 10

And he who looks may find therein

The story that I now begin.”

And in each pause the story made

Upon his violin he played,

As an appropriate interlude, 15

Fragments of old Norwegian tunes

That bound in one the separate runes,

And held the mind in perfect mood,

Entwining and encircling all

The strange and antiquated rhymes 20

With melodies of olden times;

As over some half-ruined wall,

Disjointed and about to fall,

Fresh woodbines climb and interlace,

And keep the loosened stones in place. 25

The Musician’s Tale

The Saga of King Olaf

I.

The Challenge of Thor

I AM the God Thor,

I am the War God,

I am the Thunderer!

Here in my Northland,

My fastness and fortres 5

Reign I forever!

Here amid icebergs

Rule I the nations;

This is my hammer,

Miölner the mighty; 10

Giants and sorcerers

Cannot withstand it!

These are the gauntlets

Wherewith I wield it,

And hurl it afar off; 15

This is my girdle;

Whenever I brace it,

Strength is redoubled!

The light thou beholdest

Stream through the heaven 20

In flashes of crimson,

Is but my red beard

Blown by the night-wind,

Affrighting the nations!

Jove is my brother; 25

Mine eyes are the lightning;

The wheels of my chariot

Roll in the thunder,

The blows of my hammer

Ring in the earthquake! 30

Force rules the world still,

Has ruled it, shall rule it;

Meekness is weakness,

Strength is triumphant,

Over the whole earth 35

Still is it Thor’s-Day!

Thou art a God too,

O Galilean!

And thus single-handed

Unto the combat, 40

Gauntlet or Gospel,

Here I defy thee!

II.

1 comment