Filled with these aspirations, he perishes; without having reached the perfection he longed for; and the voice heard in the air is the promise of immortality and progress ever upward. You will perceive that Excelsior, an adjective of the comparative degree, is used adverbially; a use justified by the best Latin writers.” This he afterwards found to be a mistake, and explained excelsior as the last word of the phrase Scopus meus est excelsior.

Five years after writing this poem, Mr. Longfellow made the following entry in his diary: “December 8, 1846. Looking over Brainard’s poems, I find, in a piece called The Mocking-Bird, this passage: —

Now his note

Mounts to the play-ground of the lark, high up

Quite to the sky. And then again it falls

As a lost star falls down into the marsh.

Now, when in Excelsior I said,

A voice fell, like a falling star,

Brainard’s poem was not in my mind, nor had I in all probability ever read it. Felton said at the time that the same image was in Euripides, or Pindar, I forget which. Of a truth, one cannot strike a spade into the soil of Parnassus, without disturbing the bones of some dead poet.”

Dr. Holmes remarks of Excelsior that “the repetition of the aspiring exclamation which gives its name to the poem, lifts every stanza a step higher than the one which preceded it.”

THE SHADES of night were falling fast,

As through an Alpine village passed

A youth, who bore, ‘mid snow and ice,

A banner with the strange device,

Excelsior! 5

His brow was sad; his eye beneath,

Flashed like a falchion from its sheath,

And like a silver clarion rung

The accents of that unknown tongue,

Excelsior! 10

In happy homes he saw the light

Of household fires gleam warm and bright;

Above, the spectral glaciers shone,

And from his lips escaped a groan,

Excelsior! 15

“Try not the Pass!” the old man said;

“Dark lowers the tempest overhead,

The roaring torrent is deep and wide!”

And loud that clarion voice replied,

Excelsior! 20

“Oh stay,” the maiden said, “and rest

Thy weary head upon this breast!”

A tear stood in his bright blue eye,

But still he answered, with a sigh,

Excelsior! 25

“Beware the pine-tree’s withered branch!

Beware the awful avalanche!”

This was the peasant’s last Good-night,

A voice replied, far up the height,

Excelsior! 30

At break of day, as heavenward

The pious monks of Saint Bernard

Uttered the oft-repeated prayer,

A voice cried through the startled air,

Excelsior! 35

A traveller, by the faithful hound,

Half-buried in the snow was found,

Still grasping in his hand of ice

That banner with the strange device,

Excelsior! 40

There in the twilight cold and gray,

Lifeless, but beautiful, he lay,

And from the sky, serene and far,

A voice fell, like a falling star,

Excelsior! 45

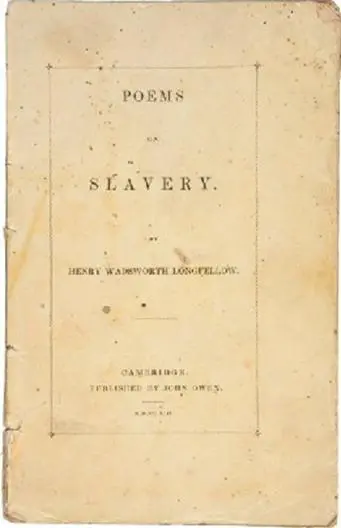

This small poetry collection was published in 1842 and was Longfellow’s first public support of abolitionism. Yet, as Longfellow himself wrote, the poems were “so mild that even a Slaveholder might read them without losing his appetite for breakfast”. A critic for The Dial agreed, calling the collection “the thinnest of all Mr. Longfellow’s thin books; spirited and polished like its forerunners; but the topic would warrant a deeper tone”. The New England Anti-Slavery Association, however, was satisfied with the collection, reprinting it for further distribution.

Frances Appleton in 1843. After a seven-year courtship with Longfellow, she agreed to be his wife and they married shortly after the publication of this collection.

CONTENTS

To William E. Channing

The Slave’s Dream

The Good Part, that shall not be taken away

The Slave in the Dismal Swamp

The Slave Singing at Midnight

The Witnesses

The Quadroon Girl

The Warning

The original title page

To William E. Channing

In the spring of 1842 Mr. Longfellow obtained leave of absence from college duties for six months and went abroad to try the virtues of the water-cure at Marienberg on the Rhine. When absent in Europe in the summer of 1842 Mr. Longfellow made an acquaintance with Ferdinand Freiligrath, the poet, which ripened into a life-long friendship. It was to this friend that he wrote shortly after his return to America [on leaving Bristol for New York]: “We sailed (or rather, paddled) out in the very teeth of a violent west wind, which blew for a week,— ‘Frau die alte sass gekehrt rückwärts nach Osten’ with a vengeance. We had a very boisterous passage. I was not out of my berth more than twelve hours for the first twelve days. I was in the forward part of the vessel, where all the great waves struck and broke with voices of thunder. There, ‘cribbed, cabined, and confined,’ I passed fifteen days. During this time I wrote seven poems on slavery; I meditated upon them in the stormy, sleepless nights, and wrote them down with a pencil in the morning. A small window in the side of the vessel admitted light into my berth, and there I lay on my back and soothed my soul with songs. I send you some copies.”

He had published the poems at once on his arrival in America in December, 1842, in a thin volume of thirty-one pages in glazed paper covers, adding to the seven an eighth, previously written, poem, The Warning. It is possible that his immediate impulse to write came from his recent association with Dickens, whose American Notes, with its “grand chapter on slavery,” he speaks of having read in London.

The book naturally received attention out of all proportion to its size. It was impossible for one at that time to range himself on one side or other of the great controversy without inviting criticism, not so much of literary art as of ethical position. To his father, Mr. Longfellow wrote: “How do you like the Slavery Poems? I think they make an impression; I have received many letters about them, which I will send to you by the first good opportunity. Some persons regret that I should have written them, but for my own part I am glad of what I have done. My feelings prompted me, and my judgment approved, and still approves.” The poem on Dr.

1 comment