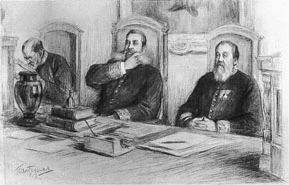

Her grandfather Leonid Pasternak was Tolstoy’s friend and one of his first illustrators, working with him on War and Peace, Resurrection, and the late short story “What Men Live By.”

The Court in Session by Leonid Pasternak (1862–1945).

THE DEATH OF IVAN ILYICH

1

During a break in the hearing of the Melvinski case in the great hall of the Law Courts, members of the judicial council and the public prosecutor met in Ivan Yegorovich Shebek’s private chambers. The conversation turned to the famous Krasov affair. Feodor Vassilievich grew heated demonstrating that it was not subject to jurisdiction. Ivan Yegorovich held his own. Piotr Ivanovich, who had not participated initially, took no part in the argument and leafed through the newly delivered Gazette.

“Gentlemen!” he said, “Ivan Ilyich is dead.”

“Not really?”

“Here; read it for yourself,” he said to Feodor Vassilievich, passing him the fresh sheets, still with their own smell.

The black-framed notice ran: “It is with deep regret that Praskovya Feodorovna Golovina informs relatives and friends of the death of her beloved husband, Ivan Ilyich Golovin, Member of the Court of Justice, on February the fourth of this year, 1882. The body will be laid to rest on Friday at 1 P.M.”

Ivan Ilyich was a colleague of the gentlemen present, and everyone liked him. He had been ill for several weeks; people said the disease was incurable. His place had been kept open for him, but it was generally assumed that, were he to die, Alexeyev might get his place, and Alexeyev’s place would be taken either by Vinnikov or Shtabel. So when they heard of the death of Ivan Ilyich, the first thought of all those present in Shebek’s chambers was how this might affect their own relocations and promotions, and those of their friends.

“Now I’ll probably get Shtabel’s place or Vinnikov’s,” thought Feodor Vassilievich. “It’s been promised to me for a long time. The promotion will bring me a raise of eight hundred rubles, apart from the allowance for office expenses.”1

“I’ll have to put in for my brother-in-law’s transfer from Kaluga,” thought Piotr Ivanovich. “My wife will be very pleased. And then no one can say I never did anything for her relatives.”

“I thought he’d never get up from his bed again,” said Piotr Ivanovich aloud. “Very sad.”

“What exactly was wrong with him?”

“The doctors couldn’t make it out. That is, they could, but each one thought something different. The last time I saw him, I thought he’d get better.”

“And I didn’t manage to visit him after the holidays. I kept meaning to go.”

“Did he have property?”

“I think something very small came to him through his wife. But really quite insignificant.”

“Yes, we’ll have to pay our respects. They lived a dreadfully long way out.”

“A long way from you, you mean. Everything’s a long way from you.”

“He just can’t forgive my living beyond the river,” said Piotr Ivanovich, smiling at Shebek. The conversation passed to the distances between different parts of the city, and they went back into court.

Apart from the considerations prompted by this death—the changes of post and possible permutations at work that were its probable consequences—the fact of a near acquaintance dying evoked in everyone who heard about it the happy feeling that he is dead, not I.

“Well, there you go, he’s dead, but I’m not,” each of them thought. And close acquaintances, the so-called friends of Ivan Ilyich, involuntarily found themselves also thinking that now they would have to go through the tedious round of social duties, driving out to the funeral and paying their condolences to the widow.

The closest of all were Feodor Vassilievich and Piotr Ivanovich.

Piotr Ivanovich had been Ivan Ilyich’s friend from their time at law school2 together, and felt under an obligation to him.

At lunchtime he told his wife about Ivan Ilyich’s death and the possibility of his brother-in-law’s transfer to their circle. Forgoing his usual after-dinner nap, he put on his tails and drove out to the Golovins.

A carriage and two cabs stood at the entrance to Ivan Ilyich’s apartment. In the entrance hall downstairs, propped against the wall by the coat stand, was the coffin lid, draped in silk, decorated with tassels and burnished gold braid. Two ladies in black were taking off their furs. He knew one of them, the sister of Ivan Ilyich, but the other was a stranger. Schwartz, a colleague, was on his way downstairs. Glimpsing Piotr Ivanovich as he entered, Schwartz stopped and winked at him from the top step, suggesting, as it were, “Ivan Ilyich has made a real mess of things, not like you and me.”

Schwartz’s face with its English side-whiskers, and indeed his entire figure, slim in evening dress, wore its usual air of elegant solemnity—a solemnity which was constantly contradicted by Schwartz’s jocular character, acquiring a particular piquancy in the present setting. Or so Piotr Ivanovich thought.

Piotr Ivanovich allowed the ladies to pass before him and followed them slowly upstairs. Schwartz did not come down but waited at the top.

1 comment