In the autumn of that year, he returned to Paris from his summer holiday in Normandy and at once set about walking the streets and visiting working people, in order to gather material for the novel.

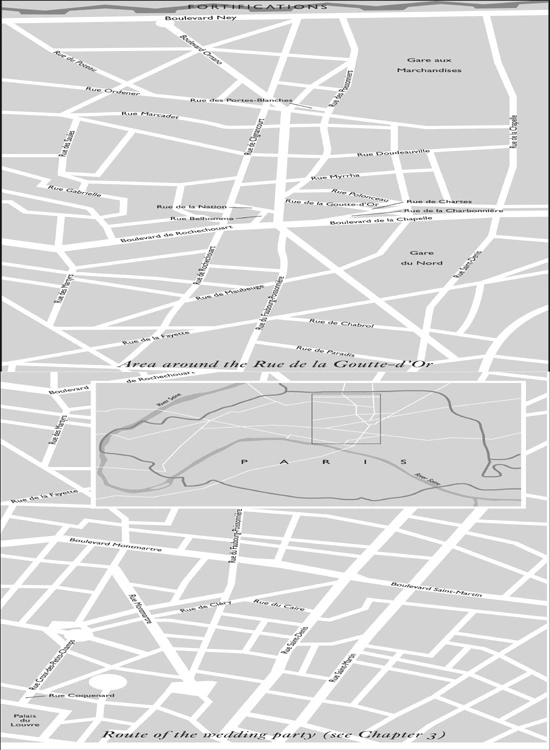

Every street through which the characters pass is named; the events of the story can be followed precisely on a contemporary map of Paris. Details of prices and wages, living conditions and language, working practices, drinking habits and delirium tremens are taken from observation or the best available sources. Zola’s notebooks survive and show how meticulously he recorded details concerning localities and trades (for example, how laundresses were paid and the different kinds of flat-iron or other tools that they used). The action of the novel is situated, year by year, with occasional references to contemporary events such as the assumption of power by Louis Bonaparte, the building of the Lariboisière Hospital or the huge urbanization programme of Baron Haussmann. Not that this is any dry sociological record; on the contrary, central to Zola’s Naturalistic literary method was the use of language to convey the sights, smells and sounds of the novel’s locations with the greatest possible precision. Few writers convey so vivid and immediate a sense of what it felt like to live in a particular place, at a particular moment in history.

The historical moment is vital. The Second Empire was to be a discrete interlude in French history, twenty years of imperial rule sandwiched between two republics; and even at the time, without the benefit of hindsight, it often appeared arbitrary or inconsequential – the very opposite of rational government for a positive and scientific age.3 Its leader, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon I, was a slightly eccentric, rootless, even bohemian figure. He had spent many years as an exile in England, becoming the hereditary leader of the Bonapartists after the death of Napoleon’s son in 1832. Returning to Paris after the Revolution of 1848, he was elected a deputy to the National Assembly under the Second Republic, then its President. In

December 1851, he carried out a putsch to make himself head of state without any constitutional constraints and proclaimed himself Emperor a year later, in December 1852.

An aura of dissolution and corruption hovered around Louis Bonaparte’s government. Republicans, naturally, hated and despised it for its illegitimacy and arbitrary exercise of power. It was characterized, too, by its ostentation and pretensions to grandeur. Abroad, the years of the Second Empire were marked by colonial expansion (in Africa, Indochina and the Pacific) and by the war in the Crimea. At home, France was at the height of an industrial revolution. Typical of the regime’s grandiose posturing, as well as its energy, were the public works carried out in Paris under Haussmann, which involved massive slum clearance and the creation of the wide boulevards that give modern Paris much of its personality. Perhaps designed to encourage gentrification of areas that might otherwise have remained solidly working class – and having the effect of making access to such areas easier for the Army and the police, in the event of popular uprisings – these ‘improvements’ also made the city more hygienic and pleasant to live in. They are specifically referred to in The Drinking Den (especially in Chapter 11).

The Empire ended after the French defeat by the Prussians at Sedan in September 1870, when Napoleon III abdicated. The following year saw the attempt to install a radical Socialist regime under the Paris Commune, which was harshly repressed by the government of Adolphe Thiers. Zola, who had spent part of the period of the Commune in Paris, continued to work hard on La Curée, the second novel in the cycle of the Rougon-Macquart; the first, La Fortune des Rougon, was about to appear as the Commune fell.

Even the most casual reader is likely to become aware that there is a structure underlying The Drinking Den. The outline of the plot is relatively simple: the rise and fall of the laundress Gervaise Macquart, in thirteen chapters (a deliberately sinister number). The culmination of the story occurs halfway through, in Chapter 7, with the great feast that Gervaise holds to celebrate her Saint’s-day. This is her triumph, but it already contains in it the seeds of her downfall, signalled by the reappearance of her lover, Lantier.

The rise of Gervaise towards this summit is mirrored in her subsequent descent from it, the chapter that precedes this turning-point describing the formation of the family and the establishment of the business, those that follow showing the progressive collapse of the business and the family, the plot describing a curve with Chapter 7 at its apex. From her victory over Virginie in the fight at the wash-house to her marriage to Coupeau and the setting up of the laundry, Gervaise has struggled successfully to acquire a position in the community around the Rue de la Goutte-d’Or and to secure the future of her family. She is respected, relatively prosperous and well liked by most of her neighbours; but her weak husband and selfish former lover are about to unravel the tidy pattern that Gervaise has tried to weave. She will lose her reputation, her business, her daughter, her husband and, finally, her life. Her dreams and aspirations come to seem bitterly ironic:

You might think that she had asked heaven for an income of thirty thousand francs and a position in life! Well, it’s true, in this life, however modest your wishes, you may still end up penniless. Not even a crust and a bed – that’s the common lot of humanity. And what made her laugh even more was to recall her fine hopes of retiring to the country, after twenty years in the laundry business. Well, the countryside was where she was headed; she wanted her little patch of greenery in the Père Lachaise [that is, in the cemetery]. (Chapter 12).4

One reason that the novel may have been disturbing to middle-class readers is that Gervaise’s aspirations are so eminently acceptable.

1 comment