A pot had hit her on the head, when the wheel sank into a drain and caused the caravan to lurch.

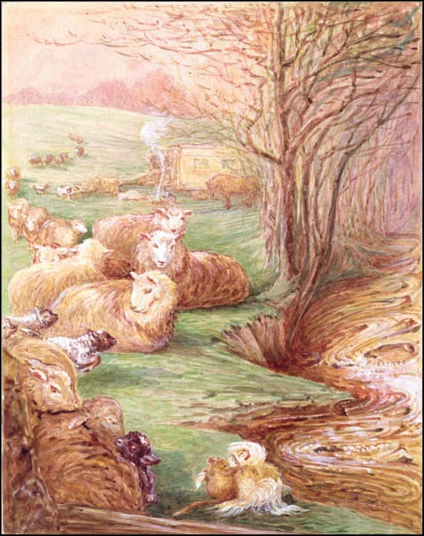

When Tuppenny woke up and peeped out, the procession had halted, and unharnessed, beside the beck. Sandy was rolling on the grass. Paddy Pig was smoking a pipe and looking pigheaded, which means obstinate. ‘You will be drowned,’ said he to Pony Billy. The pony was pawing the water with his forefeet, enjoying the splashes, and wading cautiously step by step further across. ‘Drowned? Poof!’ yapped Sandy, taking a flying leap splash into the middle; he was carried down several yards by the current before he scrambled out on the further bank. Then he swam back. ‘It’s going down,’ said Sandy, sniffing at a line of dead leaves and sticks which had been left stranded by the receding flood. Pony Billy nodded. ‘Let us pull round under the alder bushes and wait.’ ‘Then you will not go back by Pool Bridge?’ ‘What! all across those soft meadows again? No. We will lie in the sun behind this wall, and talk to the sheep while we rest.’

So they pitched their camp by the wall, where there is a watergate across the stream, and a drinking place for cattle. Pony Billy’s collar had rubbed his neck; Sandy was dog tired; Jenny Ferret was eager for firewood; everyone was content except Paddy Pig. He did his share of camp work; but he wandered away after dinner, and he was not to be found at tea time. ‘Let him alone, and he’ll come home,’ said Sandy.

‘Baa baa!’ laughed some lambs, ‘let us alone and we’ll come home, and bring our tails behind us!’ They frisked and kicked up their heels. Their mothers had come down to Wilfin Beck to drink. When their lambs went too near to Sandy, the ewes stamped their feet. They disapproved of strange dogs – even a very tired little dog, curled up asleep in the sun.

Eller-Tree Camp

The sheep watched Jenny Ferret curiously. She was collecting sticks and piling them in little heaps to dry; short, shiny sticks that had been left by the water.

Xarifa and Tuppenny were at their usual occupation, giving Tuppenny’s hair a good hard brushing. Xarifa was finding difficulty in keeping awake. The pleasant murmur of the water, the drowsiness of the other animals, the placid company of the gentle sheep, all combined to make her sleepy. Therefore, it fell to Tuppenny to converse with the sheep. They had lain down where the wall sheltered them from the wind. They chewed their cud. ‘Very fine wool,’ said the eldest ewe, Tibbie Woolstockit, after contemplating the brushing silently for several minutes. ‘It’s coming out a little,’ said Tuppenny, holding up some fluff. ‘Bring it over here, bird!’ said Tibbie to the starling, who was flitting from sheep to sheep, and running up and down on their backs. ‘Wonderfully fine; it is finer than your Scotch wool, Maggie Dinmont,’ said Tibbie Woolstockit to a black-faced ewe with curly horns, who lay beside her. ‘Aye, it’s varra fine. And its lang,’ said Maggie Dinmont, approvingly. ‘It would make lovely yarn for mittens; do you keep the combings?’ asked another ewe, named Habbitrot.

1 comment