There is no doubt that in the medieval versions of this ancient tale Cinderilla was given pantoufles de vair—i.e., of a grey, or grey and white, fur, the exact nature of which has been a matter of controversy, but which was probably a grey squirrel. Long before the seventeenth century the word vair had passed out of use, except as a heraldic term, and had ceased to convey any meaning to the people. Thus the pantoufles de vair of the fairy tale became, in the oral tradition, the homonymous pantoufles de verre, or glass slippers, a delightful improvement on the earlier version.

Being thus decked out, she got up into her coach; but her godmother, above all things, commanded her not to stay till after midnight, telling her, at the same time, that if she stayed at the ball one moment longer, her coach would be a pumpkin again, her horses mice, her coachman a rat, her footmen lizards, and her clothes become just as they were before.

She promised her godmother, she would not fail of leaving the ball before midnight; and then away she drove, scarce able to contain herself for joy. The King's son, who was told that a great Princess, whom nobody knew, was come, ran out to receive her; he gave her his hand as she alighted out of the coach, and led her into the hall, among all the company. There was immediately a profound silence, they left off dancing, and the violins ceased to play, so attentive was every one to contemplate the singular beauty of this unknown new comer. Nothing was then heard but a confused noise of,

"Ha! how handsome she is! Ha! how handsome she is!"

The King himself, old as he was, could not help ogling her, and telling the Queen softly, "that it was a long time since he had seen so beautiful and lovely a creature." All the ladies were busied in considering her clothes and head-dress, that they might have some made next day after the same pattern, provided they could meet with such fine materials, and as able hands to make them.

The King's son conducted her to the most honourable seat, and afterwards took her out to dance with him: she danced so very gracefully, that they all more and more admired her. A fine collation was served up, whereof the young Prince ate not a morsel, so intently was he busied in gazing on her. She went and sat down by her sisters, shewing them a thousand civilities, giving them part of the oranges and citrons which the Prince had presented her with; which very much surprised them, for they did not know her.

While Cinderilla was thus amusing her sisters, she heard the clock strike eleven and three quarters, whereupon she immediately made a curtesy to the company, and hasted away as fast as she could.

Being got home, she ran to seek out her godmother, and after having thanked her, she said, "she could not but heartily wish she might go next day to the ball, because the King's son had desired her." As she was eagerly telling her godmother whatever had passed at the ball, her two sisters knocked at the door which Cinderilla ran and opened.

"How long you have stayed," cried she, gaping, rubbing her eyes, and stretching herself as if she had been just awaked out of her sleep; she had not, however, any manner of inclination to sleep since they went from home.

"If thou hadst been at the ball," said one of her sisters, "thou wouldst not have been tired with it; there came thither the finest Princess, the most beautiful ever was seen with mortal eyes; she shewed us a thousand civilities, and gave us oranges and citrons." Cinderilla was transported with joy; she asked them the name of that Princess; but they told her they did not know it; and that the King's son was very anxious to learn it, and would give all the world to know who she was. At this Cinderilla, smiling, replied:

"She must then be very beautiful indeed; Lord! how happy have you been; could not I see her? Ah! dear Miss Charlotte, do lend me your yellow suit of cloaths which you wear every day!"

"Ay, to be sure!" cried Miss Charlotte, "lend my cloaths to such a dirty Cinder-breech as thou art; who's the fool then?"

Cinderilla, indeed, expected some such answer, and was very glad of the refusal; for she would have been sadly put to it, if her sister had lent her what she asked for jestingly.

The next day the two sisters were at the ball, and so was Cinderilla, but dressed more magnificently than before. The King's son was always by her, and never ceased his compliments and amorous speeches to her; to whom all this was so far from being tiresome, that she quite forgot what her godmother had recommended to her, so that she, at last, counted the clock striking twelve, when she took it to be no more than eleven; she then rose up, and fled as nimble as a deer.

The Prince followed, but could not overtake her. She left behind one of her glass slippers, which the Prince took up most carefully. She got home, but quite out of breath, without coach or footmen, and in her nasty old cloaths, having nothing left her of all her finery, but one of the little slippers, fellow to that she dropped. The guards at the palace gate were asked if they had not seen a Princess go out; who said, they had seen nobody go out, but a young girl, very meanly dressed, and who had more the air of a poor country wench, than a gentle-woman.

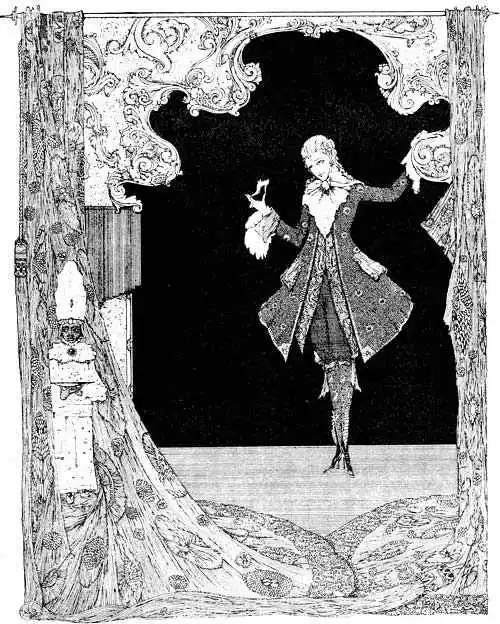

"SHE LEFT BEHIND ONE OF HER GLASS SLIPPERS, WHICH THE PRINCE TOOK UP MOST CAREFULLY"

"SHE LEFT BEHIND ONE OF HER GLASS SLIPPERS, WHICH THE PRINCE TOOK UP MOST CAREFULLY"

When the two sisters returned from the ball, Cinderilla asked them if they had been well diverted, and if the fine lady had been there. They told her, Yes, but that she hurried away immediately when it struck twelve, and with so much haste, that she dropped one of her little glass slippers, the prettiest in the world, and which the King's son had taken up; that he had done nothing but look at it during all the latter part of the ball, and that most certainly he was very much in love with the beautiful person who owned the little slipper.

What they said was very true; for a few days after, the King's son caused it to be proclaimed by sound of trumpet, that he would marry her whose foot this slipper would just fit. They whom he employed began to try it on upon the Princesses, then the duchesses, and all the Court, but in vain. It was brought to the two sisters, who did all they possibly could to thrust their feet into the slipper, but they could not effect it.

Cinderilla, who saw all this, and knew her slipper, said to them laughing:

"Let me see if it will not fit me?"

Her sisters burst out a-laughing, and began to banter her. The gentleman who was sent to try the slipper, looked earnestly at Cinderilla, and finding her very handsome, said it was but just that she should try, and that he had orders to let every one make tryal. He invited Cinderilla to sit down, and putting the slipper to her foot, he found it went on very easily, and fitted her, as if it had been made of wax. The astonishment her two sisters were in was excessively great, but still abundantly greater, when Cinderilla pulled out of her pocket the other slipper, and put it on her foot. Thereupon, in came her godmother, who having touched, with her wand, Cinderilla's cloaths, made them richer and more magnificent than any of those she had before.

And now her two sisters found her to be that fine beautiful lady whom they had seen at the ball. They threw themselves at her feet, to beg pardon for all the ill treatment they had made her undergo. Cinderilla took them up, and as she embraced them, cried that she forgave them with all her heart, and desired them always to love her.

She was conducted to the young Prince, dressed as she was; he thought her more charming than ever, and, a few days after, married her.

Cinderilla, who was no less good than beautiful, gave her two sisters lodgings in the palace, and that very same day matched them with two great lords of the court.

The Moral

Beauty's to the sex a treasure,

Still admir'd beyond all measure,

And never yet was any known,

By still admiring, weary grown.

But that rare quality call'd grace,

Exceeds, by far, a handsome face;

Its lasting charms surpass the other,

And this rich gift her kind godmother

Bestow'd on Cinderilla fair,

Whom she instructed with such care.

She gave to her such graceful mien,

That she, thereby, became a queen.

For thus (may ever truth prevail)

We draw our moral from this tale.

This quality, fair ladies, know

Prevails much more (you'll find it so)

T'ingage and captivate a heart,

Than a fine head dress'd up with art.

The fairies' gift of greatest worth

Is grace of bearing, not high birth;

Without this gift we'll miss the prize;

Possession gives us wings to rise.

Another

A great advantage 'tis, no doubt, to man,

To have wit, courage, birth, good sense, and brain,

And other such-like qualities, which we

Receiv'd from heaven's kind hand, and destiny.

But none of these rich graces from above,

To your advancement in the world will prove

If godmothers and sires you disobey,

Or 'gainst their strict advice too long you stay.

Riquet with the Tuft

Riquet with the Tuft

here was, once upon a time, a Queen, who was brought to bed of a son, so hideously ugly, that it was long disputed, whether he had human form. A Fairy, who was at his birth, affirmed, he would be very lovable for all that, since he should be indowed with abundance of wit. She even added, that it would be in his power, by virtue of a gift she had just then given him, to bestow on the person he most loved as much wit as he pleased. All this somewhat comforted the poor Queen, who was under a grievous affliction for having brought into the world such an ugly brat. It is true, that this child no sooner began to prattle, but he said a thousand pretty things, and that in all his actions there was something so taking, that he charmed every-body. I forgot to tell you, that he came into the world with a little tuft of hair upon his head, which made them call him Riquet with the Tuft, for Riquet was the family name.

Seven or eight years after this, the Queen of a neighbouring kingdom was delivered of two daughters at a birth. The first-born of these was beautiful beyond compare, whereat the Queen was so very glad, that those present were afraid that her excess of joy would do her harm. The same Fairy, who had assisted at the birth of little Riquet with the Tuft, was here also; and, to moderate the Queen's gladness, she declared, that this little Princess should have no wit at all, but be as stupid as she was pretty. This mortified the Queen extreamly, but some moments afterwards she had far greater sorrow; for, the second daughter she was delivered of, was very ugly.

"Do not afflict yourself so much, Madam," said the Fairy; "your daughter shall have so great a portion of wit, that her want of beauty will scarcely be perceived."

"God grant it," replied the Queen; "but is there no way to make the eldest, who is so pretty, have some little wit?"

"I can do nothing for her, Madam, as to wit," answered the Fairy, "but everything as to beauty; and as there is nothing but what I would do for your satisfaction, I give her for gift, that she shall have the power to make handsome the person who shall best please her."

As these Princesses grew up, their perfections grew up with them; all the public talk was of the beauty of the eldest, and the wit of the youngest.

1 comment