“Your eyesight is piercing. Them’s girls.”

The traveler apologized. “My eyes aren’t very good,” he said, hurriedly.

He was, however, quite justified in his mistake, for both riders wore wide-rimmed sombreros and rode astride at a furious pace, bandanas fluttering, skirts streaming, and one was calling in shrill command, “Oh, Bill!”

As they neared the gate the driver drew up with a word of surprise. “Why, howdy, girls, howdy!” he said, with an assumption of innocence. “Were you wishin’ fer to speak to me?”

“Oh, shut up!” commanded one of the girls, a round-faced, freckled romp. “You know perfectly well that Berrie is going home to-day—we told you all about it yesterday.”

“Sure thing!” exclaimed Bill. “I’d forgot all about it.”

“Like nothin’!” exclaimed the maid. “You’ve been countin’ the hours till you got here—I know you.”

Meanwhile her companion had slipped from her horse. “Well, good-by, Molly, wish I could stay longer.”

“Good-by. Run down again.”

“I will. You come up.”

The young passenger sprang to the ground and politely said: “May I help you in?”

Bill stared, the girl smiled, and her companion called: “Be careful, Berrie, don’t hurt yourself, the wagon might pitch.”

The youth, perceiving that he had made another mistake, stammered an apology.

The girl perceived his embarrassment and sweetly accepted his hand. “I am much obliged, all the same.”

Bill shook with malicious laughter. “Out in this country girls are warranted to jump clean over a measly little hack like this,” he explained.

The girl took a seat in the back corner of the dusty vehicle, and Bill opened conversation with her by asking what kind of a time she had been having “in the East.”

“Fine,” said she.

“Did ye get as far back as my old town?”

“What town is that, Bill?”

“Oh, come off! You know I’m from Omaha.”

“No, I only got as far as South Bend.”

The picture which the girl had made as she dashed up to the pasture gate (her hat-rim blown away from her brown face and sparkling eyes), united with the kindliness in her voice as she accepted his gallant aid, entered a deep impression on the tourist’s mind; but he did not turn his head to look at her—perhaps he feared Bill’s elbow quite as much as his guffaw—but he listened closely, and by listening learned that she had been “East” for several weeks, and also that she was known, and favorably known, all along the line, for whenever they met a team or passed a ranch some one called out, “Hello, Berrie!” in cordial salute, and the men, old and young, were especially pleased to see her.

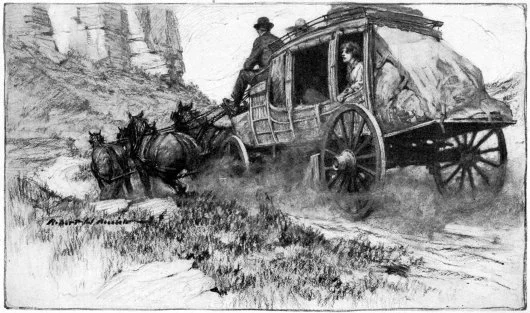

THE GIRL BEHIND HIM WAS A WONDROUS PART OF THIS WILD AND UNACCOUNTABLE COUNTRY

Meanwhile the stage rose and fell over the gigantic swells like a tiny boat on a monster sea, while the sun blazed ever more fervently from the splendid sky, and the hills glowed with ever-increasing tumult of color. Through this land of color, of repose, of romance, the young traveler rode, drinking deep of the germless air, feeling that the girl behind him was a wondrous part of this wild and unaccountable country.

He had no chance to study her face again till the coach rolled down the hill to “Yancy’s,” where they were to take dinner and change horses.

Yancy’s ranch-house stood on the bank of a fine stream which purled—in keen defiance of the hot sun—over a gravel bed, so near to the mountain snows that their coolness still lingered in the ripples. The house, a long, low, log hut, was fenced with antlers of the elk, adorned with morning-glory vines, and shaded by lofty cottonwood-trees, and its green grass-plat—after the sun-smit hills of the long morning’s ride—was very grateful to the Eastern man’s eyes.

With intent to show Bill that he did not greatly fear his smiles, the youth sprang down and offered a hand to assist his charming fellow-passenger to alight; and she, with kindly understanding, again accepted his aid—to Bill’s chagrin—and they walked up the path side by side.

“This is all very new and wonderful to me,” the young man said in explanation; “but I suppose it’s quite commonplace to you—and Bill.”

“Oh no—it’s home!”

“You were born here?”

“No, I was born in the East; but I’ve lived here ever since I was three years old.”

“By East you mean Kansas?”

“No, Missouri,” she laughed back at him.

She was taller than most women, and gave out an air of fine unconscious health which made her good to see, although her face was too broad to be pretty. She smiled easily, and her teeth were white and even. Her hand he noticed was as strong as steel and brown as leather. Her neck rose from her shoulders like that of an acrobat, and she walked with the sense of security which comes from self-reliant strength.

She was met at the door by old lady Yancy, who pumped her hand up and down, exclaiming: “My stars, I’m glad to see ye back! ’Pears like the country is just naturally goin’ to the dogs without you. The dance last Saturday was a frost, so I hear, no snap to the fiddlin’, no gimp to the jiggin’. It shorely was pitiful.”

Yancy himself, tall, grizzled, succinct, shook her hand in his turn. “Ma’s right, girl, the country needs ye. I’m scared every time ye go away fer fear some feller will snap ye up.”

She laughed. “No danger. Well, how are ye all, anyway?” she asked.

“All well, ‘ceptin’ me,” said the little old woman. “I’m just about able to pick at my vittles.”

“She does her share o’ the work, and half the cook’s besides,” volunteered Yancy.

“I know her,” retorted Berrie, as she laid off her hat. “It’s me for a dip. Gee, but it’s dusty on the road!”

The young tourist—he signed W. W. Norcross in Yancy’s register—watched her closely and listened to every word she spoke with an intensity of interest which led Mrs.

1 comment