And what I'm afraid is that these other gentlemen who are here along with me are going to have a grudge against me because I've been called for a cross-examination twice running, and they've not been there at all yet this evening. It's enough to make them jealous of me."

"Clear out and shut your row," was the reply to Schweik's considerate representations.

Schweik again stood in the presence of the criminal-faced gentleman who, without any preliminaries, asked him in a harsh and relentless tone :

"Do you admit everything?"

Schweik fixed his kindly blue eyes upon the pitiless person and said mildly :

"If you want me to admit it, sir, then I will. It can't do me any harm. But if you was to say: 'Schweik, don't admit anything,' I'll argue the point to my last breath."

The severe gentleman wrote something on his documents and, handing Schweik a pen, told him to sign.

And Schweik signed Bretschneider's depositions, with the following addition :

All the above-mentioned accusations against me are based upon

truth.

Josef Schweik.

When he had signed, he turned to the severe gentleman :

"Is there anything else for me to sign? Or am I to come back in the morning?"

"You'll be taken to the criminal court in the morning," was the answer.

"What time, sir? You see, I wouldn't like to oversleep myself, whatever happens."

"Get out!" came a roar for the second time that day from the other side of the table before which Schweik had stood.

On the way back to his new abode, which was provided with a grating, Schweik said to the police-sergeant escorting him :

"Everything here runs as smooth as clockwork."

As soon as the door had closed behind him, his fellow-prisoners overwhelmed him with all sorts of questions, to which Schweik replied brightly :

"I've just admitted I probably murdered the Archduke Ferdinand."

And as he lay down on the mattress, he said :

"It's a pity we haven't got an alarm clock here."

But in the morning they woke him up without an alarm clock, and precisely at six Schweik was taken away in the Black Maria to the county criminal court.

"The early bird catches the worm," said Schweik to his fellow-travellers, as the Black Maria was passing out through the gates of the police headquarters.

3.

Schweik Before the Medical Authorities.

The clean, cosy cubicles of the county criminal court produced a very favourable impression upon Schweik. The whitewashed walls, the black-leaded gratings and the fat warder in charge of prisoners under remand, with the purple facings and purple braid on his official cap. Purple is the regulation colour not only here, but also at religious ceremonies on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.

The glorious history of the Roman domination of Jerusalem was being enacted all over again. The prisoners were taken out and brought before the Pilâtes of 1914 down below on the ground floor. And the examining justices, the Pilâtes of the new epoch,

instead of honourably washing their hands, sent out for stew and Pilsen beer, and kept on transmitting new charges to the public prosecutor.

Here, for the greater part, all logic was in abeyance and it was red tape which was victorious, it was red tape which throttled, it was red tape which caused lunacy, it was red tape which made a fuss, it was red tape which chuckled, it was red tape which threatened and never pardoned. They were jugglers with the legal code, high priests of the letter of the law, who gobbled up accused persons, the tigers in the Austrian jungle, who measured the extent of their leap upon the accused according to the statute book.

The exception consisted of a few gentlemen (just as at the police headquarters) who did not take the law too seriously, for everywhere you will find wheat among the tares.

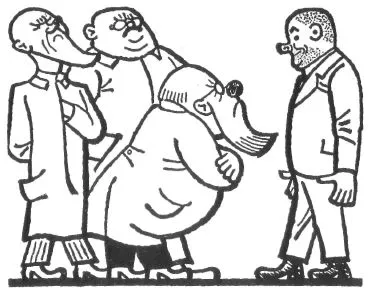

It was to one of these gentlemen that Schweik was conducted for cross-examination. When Schweik was led before him, he asked him with his inborn courtesy to sit down, and then said :

"So you're this Mr. Schweik?"

"I think I must be," replied Schweik, "because my dad was called Schweik and my mother was Mrs. Schweik. I couldn't disgrace them by denying my name."

A bland smile flitted across the face of the examining counsel.

"This is a fine business you've been up to. You've got plenty on your conscience."

"I've always got plenty on my conscience," said Schweik, smiling even more blandly than the counsel himself. "I bet I've got more on my conscience than what you have, sir."

"I can see that from the statement you signed," said the legal dignitary, in the same kindly tone. "Did they bring any pressure to bear upon you at the police headquarters?"

"Not a bit of it, sir. I myself asked them whether I had to sign it and when they said I had to, why, I just did what they told me. It's not likely I'm going to quarrel with them over my own signature. I shouldn't be doing myself any good that way. Things have got to be done in proper order."

"Do you feel quite well, Mr. Schweik?"

"I wouldn't say quite well, your worship. I've got rheumatism and I'm using embrocation for it."

The old gentleman again gave a kindly smile. "Suppose we were to have you examined by the medical authorities."

"I don't think there's much the matter with me and it wouldn't be fair to waste the gentlemen's time. There was one doctor examined me at the police headquarters."

"All the same, Mr. Schweik, we'll have a try with the medical authorities. We'll appoint a little commission, we'll have you placed under observation, and in the meanwhile you'll have a nice rest. Just one more question : According to the statement you're supposed to have said that now a war's going to break out soon."

"Yes, your worship, it'll break out at any moment now."

"And do you ever feel run down at all?"

"No, sir, except that once I nearly got run down by a motor car, but that's years and years ago."

That concluded the cross-examination. Schweik shook hands with the legal dignitary and on his return to the cell he said to his neighbours :

"Now they're going to have me examined by the medical authorities on account of this murder of Archduke Ferdinand."

"I've already been examined by the medical authorities," said one young man, "that was when I was had up in court over some carpets. They said I was weak-minded. Now I've embezzled a steam-threshing machine and they can't touch me.

1 comment