The disappointed doctors reported that he was "a malingerer of weak intellect," and as they discharged him before lunch, it caused quite a little scene. Schweik declared that a man cannot be ejected from a lunatic asylum without having been given his lunch first. This disorderly behaviour was stopped by a police officer who had been summoned by the asylum porter and who conveyed Schweik to the commissariat of police.

5.

Schweik at the Commissariat of Police.

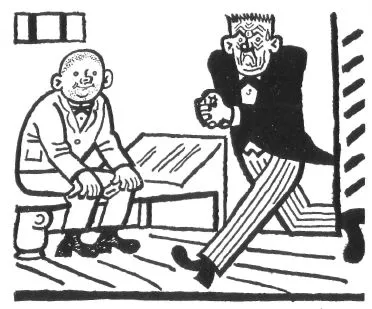

Schweik's bright sunny days in the asylum were followed by hours laden with persecution. Police Inspector Braun arranged the meeting with Schweik as brutally as if he were a Roman hangman during the delightful reign of Nero. Just as they used to say in harsh tones: "Throw this rascal of a Christian to the lions," Inspector Braun said : "Shove him in clink."

Not a word more or less. But as he said it, the eyes of Inspector Braun shone with a strange and perverse joy.

Schweik bowed and said with a certain pride : "I'm ready, gentlemen. I suppose that clink means being in a cell and that's not so bad."

"Here, not so much of your lip," replied the police officer, whereupon Schweik remarked :

"I'm an easy-going sort of chap, and grateful for anything you do for me."

In the cell a man was sitting on a bench, deep in meditation. He sat there listlessly, and from his appearance it was obvious that when the key grated in the lock of the cell he did not imagine this to be the token of approaching liberty.

"Good-day to you, sir," said Schweik, sitting down by his side on the bench. "I wonder what time it can be?"

"Time is not my master," retorted the meditative man.

"It's not so bad here," resumed Schweik. "Why, they took the trouble to plane the wood this bench is made of."

The solemn man did not reply. He stood up and began to walk rapidly to and fro in the tiny space between door and bench, as if he were in a hurry to save something.

Schweik meanwhile inspected with interest the inscriptions daubed upon the walls. There was one inscription in which an anonymous prisoner had vowed a life-and-death struggle with the police. The wording was : "You won't half cop it." Another had written : "Rats to you, fatheads." Another merely recorded a plain fact : "I was locked up here on June 5, 1913, and got fair treatment." Next to this some poetic soul had inscribed the verses :

I sit in sorrow by the stream. The sun is hid behind the hill. I watch the uplands as they gleam, Where my beloved tarries still.

The man who was now running to and fro between door and bench, as if he were anxious to win a Marathon race, came to a standstill, and sat down breathless in his old place, sank his head in his hands and suddenly shouted :

"Let me out !"

Then, talking to himself: "No, they won't let me out, they won't, they won't. I've been here since six o'clock this morning."

He then became unexpectedly communicative. He rose up and inquired of Schweik :

"You don't happen to have a strap on you so that I could end it all?"

"Pleased to oblige," answered Schweik, undoing his strap. "I've never seen a man hang himself with a strap in a cell."

"It's a nuisance, though," he continued, looking round about, "that there isn't a hook here. The bolt by the window wouldn't hold you. I tell you what you might do, though. You could kneel down by the bench and hang yourself that way, like the monk who hanged himself on a crucifix because of a young Jewess. I'm very keen on suicides. Go it !"

The gloomy man into whose hands Schweik had thrust the strap looked at it, threw it into a corner and burst out crying, wiping away his tears with his grimy hands and yelling the while. "I've got children! I'm here for drunkenness and immorality! Heavens above, my poor wife! What will they say at the office? I've got children! I'm here for drunkenness and immorality," and so ad infinitum.

At last, however, he calmed down a little, went to the door and began to thump and beat at it with his fist. From behind the door could be heard steps and a voice :

"What do you want?"

"Let me out," he said in a voice which sounded as if he had nothing left to live for.

"Where to?" was the answer from the other side.

"To my office," replied the unhappy father, husband, clerk, drunkard and profligate.

Amid the stillness of the corridor could be heard laughter, dreadful laughter, and the steps moved away again.

"It looks to me as if that chap ain't fond of you, laughing at you like that," said Schweik, while the desperate man sat down again beside him. "Those policemen are capable of anything when they're in a wax. Just you sit down quietly if you don't want to hang yourself, and wait how things turn out. If you're in an office, with a wife and children, it's pretty bad for you, I must admit. I suppose you're more or less certain of getting the sack, eh?"

"I don't know," sighed the man, "because I can't remember what I did. I only know I got thrown out from somewhere and

I wanted to go back and light my cigar.

1 comment