Palivec :

"I've had five beers and a couple of sausages with a roll. Now let me have a cherry brandy and I must be off, as I'm arrested."

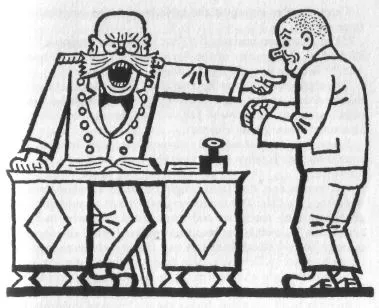

Bretschneider showed Mr. Palivec his badge, looked at Mr. Palivec for a moment and then asked :

"Are you married?"

"Yes."

"And can your wife carry on the business during your absence?"

"Yes."

"That's all right, then, Mr. Palivec," said Bretschneider breezily. "Tell your wife to step this way ; hand the business over to her, and we'll come for you in the evening."

"Don't you worry about that," Schweik comforted him. "I'm being run in only for high treason."

"But what about me?" lamented Mr. Palivec. "I've been so careful what I said."

Bretschneider smiled and said triumphantly :

"I've got you for saying that the flies left their trade-mark on the Emperor. You'll have all that stuff knocked out of your head."

And Schweik left The Flagon in the company of the plainclothes policeman. When they reached the street Schweik, fixing his good-humoured smile upon Bretschneider's countenance, inquired :

"Shall I get off the pavement?"

"How d'you mean?"

"Why, I thought now I'm arrested I mustn't walk on the pavement."

When they were passing through the entrance to the police headquarters, Schweik said :

"Well, that passed off very nicely. Do you often go to The Flagon?"

And while they were leading Schweik into the reception bureau, Mr. Palivec at The Flagon was handing over the business to his weeping wife, whom he was comforting in his own special manner :

"Now stop crying and don't make all that row. What can they do to me on account of the Emperor's portrait where the flies left their trade-mark?"

And thus Schweik, the good soldier, intervened in the World War in that pleasant, amiable manner which was so peculiarly his. It will be of interest to historians to know that he saw far into the future. If the situation subsequently developed otherwise than he expounded it at The Flagon, we must take into account the fact that he lacked a preliminary diplomatic training.

2.

Schweik, the Good Soldier, at the Police Headquarters.

The Sarajevo assassination had filled the police headquarters with numerous victims. They were brought in, one after the other, and the old inspector in the reception bureau said in his good-humoured voice: "This Ferdinand business is going to cost you dear." When they had shut Schweik up in one of the numerous dens on the first floor, he found six persons already assembled there. Five of them were sitting round the table, and in a corner a middle-aged man was sitting on a mattress as if he were holding aloof from the rest.

Schweik began to ask one after the other why they had been arrested.

From the five sitting at the table he received practically the same reply :

"That Sarajevo business." "That Ferdinand business." "It's all through that murder of the Archduke." "That Ferdinand affair." "Because they did the Archduke in at Sarajevo."

The sixth man who was holding aloof from the other five said that he didn't want to have anything to do with them because he didn't want any suspicion to fall on him. He was there only for attempted robbery with violence.

Schweik joined the company of conspirators at the table, who were telling each other for at least the tenth time how they had got there.

All, except one, had been caught either in a public house, a wineshop or a café. The exception consisted of an extremely fat gentleman with spectacles and tear-stained eyes who had been arrested in his own home because two days before the Sarajevo outrage he had stood drinks to two Serbian students, and had been observed by Detective Brix drunk in their company at the Montmartre night club where, as he had already confirmed by his signature on the report, he had again stood them drinks.

In reply to all questions during the preliminary investigations at the commissariat of police he had uttered a stereotyped lament :

"I'm a stationer."

Whereupon he had received an equally stereotyped reply :

"That's no excuse."

A little fellow, who had come to grief in a wineshop, was a teacher of history and he had been giving the wine merchant the history of various political murders. He had been arrested at the moment when he was concluding a psychological analysis of all assassinations with the words :

"The idea underlying assassination is as simple as the egg of Columbus."

Which remark the commissary of police had amplified at the cross-examination thus :

"And as sure as eggs are eggs, there's quod in store for you."

The third conspirator was the chairman of the "Dobromil" Benevolent Society. On the day of the assassination the "Dobro-

mil" had arranged a garden party, combined with a concert. A sergeant of gendarmes had called upon the merrymakers to disperse, because Austria was in mourning, whereupon the chairman of the "Dobromil" had remarked good-humouredly :

"Just wait a moment till they've played Hej Slované."1

Now he was sitting there with downcast heart and lamenting :

"They elect a new chairman in August and if I'm not home by then I may not be reelected. This is my tenth term as chairman and I'd never get over the disgrace of it."

The late Ferdinand had played a queer trick on the fourth conspirator, a man of sterling character and unblemished scutcheon. For two whole days he had avoided any conversation on the subject of Ferdinand, till in the evening when he was playing cards in a café, he had won a trick by trumping the king of clubs.

"Bang goes the king—just like at Sarajevo."

As for the fifth man, who was there, as he put it, because they did the Archduke in at Sarajevo, his hair and beard were bristling with terror, so that his head recalled that of a fox terrier. He hadn't spoken a word in the restaurant where he was arrested— in fact he hadn't even read the newspaper reports about Ferdinand's assassination, but was sitting at a table all alone, when an unknown man had sat down opposite him and said in hurried tones : -

"Have you read it?"

"No."

"Do you know about it?"

"No."

"Do you know what it's all about?"

"No, I can't be bothered about it."

"You ought to take an interest in it all the same."

"I don't know what I ought to take an interest in. I'll just smoke a cigar, have a few drinks, have a bit of supper, but I won't read the papers. The papers are full of lies. Why should I upset myself?"

"So you didn't take any interest even in the Sarajevo murder?"

"I don't take any interest in any murders, whether they're in

1 Czech popular song.

Prague, Vienna, Sarajevo or London. That's the business of the authorities, the law courts and the police.

1 comment