Stephen kept close by him till the troopers were all through. Then he turned and spoke to the apprentices, and they nodded assent. The Commandant checked his horse for an instant when he was half-way through the gate, and bent down and took Stephen's hand to shake it in farewell. Stephen took his hand with marvellous friendliness, and held it, and would not let him go. But the apprentices edged cautiously nearer and nearer the gate.

"Enough, man, enough!" laughed the Commandant. "We are not parting for ever."

"I trust not, sir, I trust not," said Stephen earnestly, still holding his hand.

"Come, let me go. See, the gate-warden wants to shut the gate!"

"True!" said Stephen. "Good-bye then, sir. Hallo, hallo! stop, stop! Oh, the young rascals!"

For even as Stephen spoke, two of the apprentices had darted through the half-closed gate, and run swiftly forward into the gloom of the night. Stephen swore an oath.

"The rogues!" he cried. "They were to have worked all night to finish an image of Our Lady! And now I shall see no more of them till to-morrow! They shall pay for their prank then, by heaven they shall!" But the Commandant laughed.

"I am sorry I can't catch them for you, friend Stephen," said he, "but I have other fish to fry. Well, boys will be boys. Don't be too hard on them when they return."

"They must answer for what they do," said Stephen; and the Commandant rode on and the gates were shut.

Then the Princess Osra said:

"Will they escape, Stephen?"

"They have money in their purses, love in their hearts, and an angry King behind them. I should travel quickly, madame, if I were so placed."

The Princess looked through the grating of the gate.

"Yes," she said, "they have all those. How happy they must be, Stephen! But what am I to do?"

Stephen made no answer and they walked back in silence to his house. It may be that they were wondering whether Prince Henry and the Countess would escape. Yet it may be that they thought of something else. When they reached the house, Stephen bade the Princess go into the inner room and resume her own dress that she might return to the palace, and that it might not be known where she had been nor how she had aided her brother to evade the King's prohibition; and when she, still strangely silent, went in as he bade her, he took his great staff in his hand, and stood on the threshold of the house, his head nearly touching the lintel and his shoulders filling almost all the space between door-post and door-post.

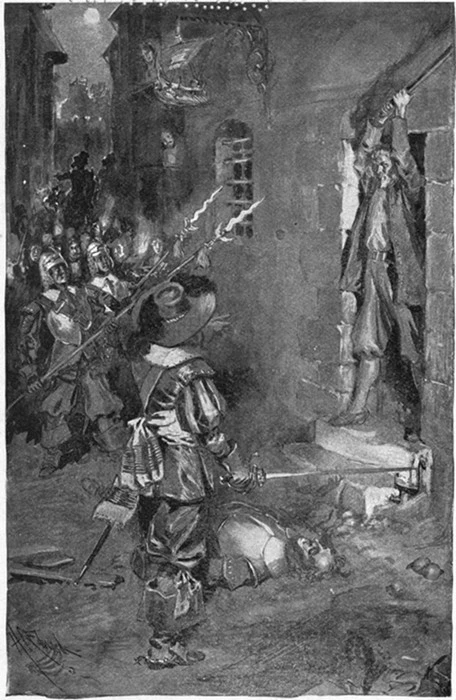

"stephen stood on the threshold with his staff in his hand."—Page 37.

When he had stood there a little while, the same Sergeant of the Guard, recollecting (now that the fire at the fruit-seller's was out) that he had never searched the house of the smith, came again with his four men, and told Stephen to stand aside and allow him to enter the house.

"For I must search it," he said, "or my orders will not be performed."

"Those whom you seek are not here," said Stephen.

"That I must see for myself," answered the Sergeant. "Come, smith, stand aside."

When the Princess heard the voices outside, she put her head round the door of the inner room, and cried in great alarm to Stephen:

"They must not come in, Stephen. At any cost they must not come in!"

"Do not be afraid, madame, they shall not come in," said he.

"I heard a voice in the house," exclaimed the Sergeant.

"It is nothing uncommon to hear in a house," said Stephen, and he grasped more firmly his great staff.

"Will you make way for us?" demanded the Sergeant. "For the last time, will you make way?"

Stephen's eyes kindled; for though he was a man of peace, yet his strength was great and he loved sometimes to use it; and above all, he loved to use it now at the bidding and in protection of his dear Princess. So he answered the Sergeant from between set teeth:

"Over my dead body you can come in."

Then the Sergeant drew his sword and his men set their halberds in rest, and the Sergeant, crying, "In the King's name!" came at Stephen with drawn sword and struck fiercely at him. But Stephen let the great staff drop on the Sergeant's shoulder, and the Sergeant's arm fell powerless by his side. Thereupon the Guards cried aloud, and people began to come out of their houses, seeing that there was a fight at Stephen's door. And Stephen's eyes gleamed, and when the Guards thrust at him, he struck at them, and two of them he stretched senseless on the ground; for his height and reach were such that he struck them before they could come near enough to touch him, and having no firearms they could not bring him down.

The Princess, now fully dressed in her own garments, came out into the outer room, and stood there looking at Stephen. Her bosom rose and fell, and her eyes grew dim as she looked; and growing very eager, and being very much moved, she kept murmuring to herself, "I have not said no thrice!" And she spent no thought on the Countess or her brother, nor on how she was to return undetected to the palace, but saw only the figure of Stephen on the threshold, and heard only the cries of the Guards who assaulted him. It seemed to her a brave thing to have such a man to fight for her, and to offer his life to save her shame.

Old King Henry was not a patient man, and when he had waited two hours without news of son, daughter, or Countess, he flew into a mighty passion and sent one for his horse, and another for Rudolf's horse, and a third for Rudolf himself; and he drank a draught of wine, and called to Rudolf to accompany him, that they might see for themselves what the lazy hounds of Guards were doing, that they had not yet come up with the quarry. Prince Rudolf laughed and yawned and wished his brother at the devil, but mounted his horse and rode with the King. Thus they traversed the city, riding swiftly, the old King furiously upbraiding every officer and soldier whom he met; then they rode to the gate; and all the gate-wardens said that nobody had gone out, save that one gate-warden admitted that two apprentices of Stephen the silversmith had contrived to slip out when the gates were open to let the troopers pass. But the King made nothing of it, and, turning with his son, rode up the street where Stephen lived.

1 comment