I remember I heard myself speaking to her, as if it was something I’d always wanted to say: “Well, you know what you can do with your pipe dream now, you damned bitch!” He stops with a horrified start, as if shocked out of a nightmare, as if he couldn’t believe he heard what he had just said. He stammers. No! I never—!

PARRITT

To

LARRY—sneeringly.

Yes, that’s it! Her and the damned old Movement pipe dream! Eh, Larry?

HICKEY

Bursts into frantic denial.

No! That’s a lie! I never said—! Good God, I couldn’t have said that!

If I did, I’d gone insane! Why, I loved Evelyn better than anything in life!

He appeals brokenly to the crowd.

Boys, you’re all my old pals! You’ve known old Hickey for years! You know I’d never—

His eyes fix on HOPE.

You’ve known me longer than anyone, Harry. You know I must have been insane, don’t you, Governor?

Rather than a demystifier, whether of self or others, Hickey is revealed as a tragic enigma, who cannot sell himself a coherent account of the horror he has accomplished. Did he slay Evelyn because of a hope—hers or his—or because of a mutual despair? He does not know, nor does O’Neill, nor do we. Nor does anyone know why Parritt betrayed his mother, the anarchist activist, and her comrades and his. Slade condemns Parritt to a suicide’s death, but without persuading us that he has uncovered the motive for so hideous a betrayal. Caught in a moral dialectic of guilt and suffering, Parritt appears to be entirely a figure of pathos, without the weird idealism that makes Hickey an interesting instance of High Romantic tragedy.

Parritt at least provokes analysis; the drama’s failure is Larry Slade, much against O’Neill’s palpable intentions, which were to move his surrogate from contemplation to action. Slade ought to end poised on the threshold of a religious meditation on the vanity of life in a world from which God is absent. But his final speech, expressing a reaction to Parritt’s suicide, is the weakest in the play:

LARRY

In a whisper of horrified pity.

Poor devil!

A long-forgotten faith returns to him for a moment and he mumbles.

God rest his soul in peace.

He opens his eyes—with a bitter self-derision.

Ah, the damned pity—the wrong kind, as Hickey said! Be God, there’s no hope! I’ll never be a success in the grandstand—or anywhere else! Life is too much for me! I’ll be a weak fool looking with pity at the two sides of everything till the day I die! With an intense bitter sincerity.

May that day come soon!

He pauses startledly, surprised at himself—then with a sardonic grin. Be God, I’m the only real convert to death Hickey made here. From the bottom of my coward’s heart I mean that now!

The momentary return of Catholicism is at variance with the despair of the death-drive here, and Slade does not understand that he has not been converted to any sense of death, at all. His only strength would be in emulating Hickey’s tragic awareness between right and right, but of course without following Hickey into violence: “I’ll be a weak fool looking with pity at the two sides of everything till the day I die!” That vision of the two sides, with compassion, is the only hope worthy of the dignity of any kind of tragic conception. O’Neill ended by exemplifying Yeats’s great apothegm: he could embody the truth, but he could not know it.

Characters

HARRY HOPE,

proprietor of a saloon and rooming house*

ED MOSHER,

Hope’s brother-in-law, one-time circus man*

PAT MCGLOIN,

one-time Police Lieutenant*

WILLIE OBAN, a Harvard Law School alumnus*

JOE MOTT, one-time proprietor of a Negro gambling house

PIET WETJOEN (“THE GENERAL”),

one-time leader of a Boer commando*

CECIL LEWIS (“THE CAPTAIN”),

one-time Captain of British infantry*

JAMES CAMERON (“JIMMY TOMORROW”),

one-time Boer War correspondent*

HUGO KALMAR,

one-time editor of Anarchist periodicals

LARRY SLADE,

one-time Syndicalist-Anarchist*

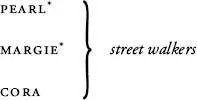

ROCKY PIOGGI, night bartender*

DON PARRITT*

CHUCK MORELLO,

day bartender*

THEODORE HICKMAN (HICKEY), a hardware salesman

MORAN

LIEB

* Roomers at Harry Hope’s.

Scenes

ACT ONE

Back room and a section of the bar at Harry Hope’s—early morning in summer, 1912.

ACT TWO

Back room, around midnight of the same day.

ACT THREE

Bar and a section of the back room—morning of the following day.

ACT FOUR

Same as Act One. Back room and a section of the bar—around 1:30 A.M. of the next day.

Harry HOPE’s is a Raines-Law hotel of the period, a cheap ginmill of the five-cent whiskey, last-resort variety situated on the downtown West Side of New York. The building, owned by Hope, is a narrow five-story structure of the tenement type, the second floor a flat occupied by the proprietor. The renting of rooms on the upper floors, under the Raines-Law loopholes, makes the establishment legally a hotel and gives it the privilege of serving liquor in the back room of the bar after closing hours and on Sundays, provided a meal is served with the booze, thus making a back room legally a hotel restaurant. This food provision was generally circumvented by putting a property sandwich in the middle of each table, an old desiccated ruin of dust-laden bread and mummified ham or cheese which only the drunkest yokel from the sticks ever regarded as anything but a noisome table decoration. But at Harry Hope’s, Hope being a former minor Tammanyite and still possessing friends, this food technicality is ignored as irrelevant, except during the fleeting alarms of reform agitation. Even HOPE’s back room is not a separate room, but simply the rear of the barroom divided from the bar by drawing a dirty black curtain across the room.

Act One

SCENE

The back room and a section of the bar of HARRY HOPE’S

saloon on an early morning in summer, 1912. The right wall of the back room is a dirty black curtain which separates it from the bar. At rear, this curtain is drawn back from the wall so the bartender can get in and out. The back room is crammed with round tables and chairs placed so close together that it is a difficult squeeze to pass between them. In the middle of the rear wall is a door opening on a hallway. In the left corner, built out into the room, is the toilet with a sign “This is it” on the door. Against the middle of the left wall is a nickel-in-the-slot phonograph. Two windows, so glazed with grime one cannot see through them, are in the left wall, looking out on a backyard. The walls and ceiling once were white, but it was a long time ago, and they are now so splotched, peeled, stained and dusty that their color can best be described as dirty. The floor, with iron spittoons placed here and there, is covered with sawdust. Lighting comes from single wall brackets, two at left and two at rear.

There are three rows of tables, from front to back.

1 comment