It is from these that I speak. Every man’s position is in fact too simple to be described. I have sworn no oath. I have no designs on society, or nature, or God. I am simply what I am, or I begin to be that. I live in the present. I only remember the past, and anticipate the future. I love to live. I love reform better than its modes. There is no history of how bad became better. I believe something, and there is nothing else but that. I know that I am. I know that another is who knows more than I, who takes interest in me, whose creature, and yet whose kindred, in one sense, am I. I know that the enterprise is worthy. I know that things work well. I have heard no bad news.”

The man who wrote thus might be pardoned for exaggeration, for mysticism, for sharpness of speech, though these were a thousandfold more and worse than are to be found anywhere in Thoreau’s books. To call him a prig, or an idler, or a shirk, is not to damage him. No doubt he had his imperfections. No doubt, too, they were of a kind to be easily turned to ridicule. All virtue is attended by its shadow. Thoreau knew this, not only as a general truth, but as a truth specially applicable to himself. His independence, his individuality, were not without an obverse side. “I am perhaps more willful than others,” he wrote in his diary. “I sometimes seem to myself to owe all my little success, all for which men commend me, to my vices.” But he was not for that reason to be deterred from following his own path. What other path should he follow? It was foolish for him to live in a hut in the woods, men said,—as if they knew the difference between folly and wisdom! But meanwhile he lived there, and wrote his book; and though it is early yet to talk of American classics, or even, perhaps, of American literature, it is beginning to be evident that Time, the ultimate critic, has taken Thoreau’s part, and is very unlikely to forget him in the day of final award.

BRADFORD TORREY.

I

Economy

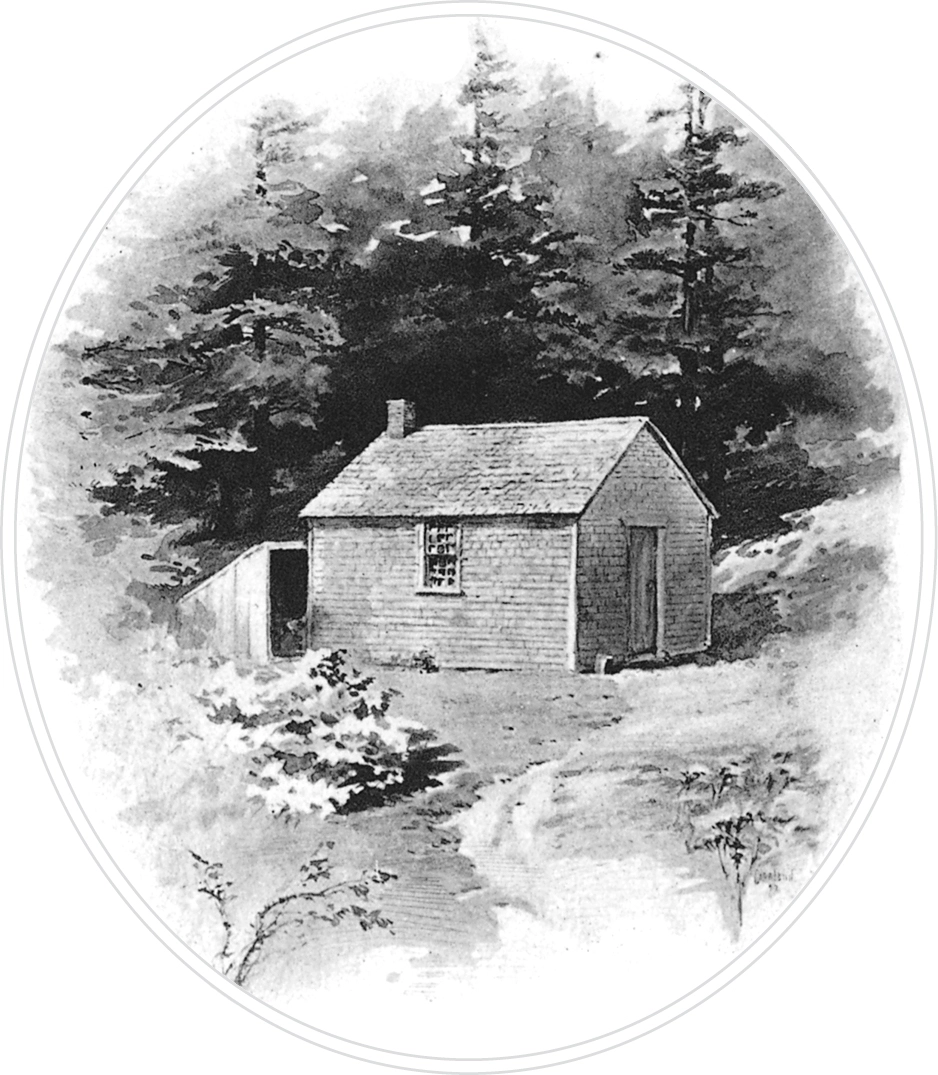

W hen I wrote the following pages, or rather the bulk of them, I lived alone, in the woods, a mile from any neighbor, in a house which I had built myself, on the shore of Walden Pond, in Concord, Massachusetts, and earned my living by the labor of my hands only. I lived there two years and two months. At present I am a sojourner in civilized life again.

I should not obtrude my affairs so much on the notice of my readers if very particular inquiries had not been made by my townsmen concerning my mode of life, which some would call impertinent, though they do not appear to me at all impertinent, but, considering the circumstances, very natural and pertinent. Some have asked what I got to eat; if I did not feel lonesome; if I was not afraid; and the like. Others have been curious to learn what portion of my income I devoted to charitable purposes; and some, who have large families, how many poor children I maintained. I will therefore ask those of my readers who feel no particular interest in me to pardon me if I undertake to answer some of these questions in this book.

1 comment