The Last Days of Mankind

The Last Days of Mankind

The Last Days of Mankind

KARL KRAUS

THE COMPLETE TEXT

TRANSLATED BY FRED BRIDGHAM AND EDWARD TIMMS

WITH A GLOSSARY AND INDEX

The Margellos World Republic of Letters is dedicated to making literary works from around the globe available in English through translation. It brings to the English-speaking world the work of leading poets, novelists, essayists, philosophers, and playwrights from Europe, Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East to stimulate international discourse and creative exchange.

The translation of this book was supported by the Austrian Federal Chancellery—Division for the Arts.

Originally published as Die letzten Tage der Menschheit. Translated 2015 by Fred Bridgham and Edward Timms. English translation, introduction, and afterword copyright © 2015 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office).

Set in Electra type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America.

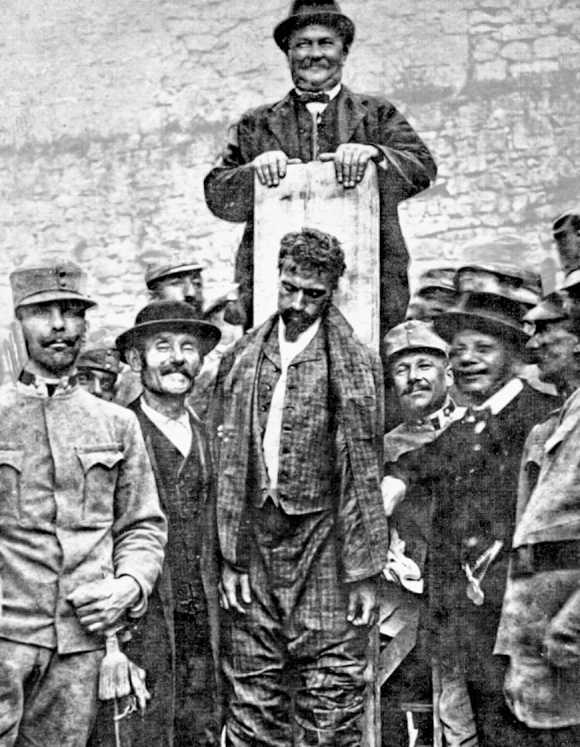

Frontispiece: The execution of Cesare Battisti, 12 July 1916

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015939015

ISBN 978-0-300-20767-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

CONTENTS

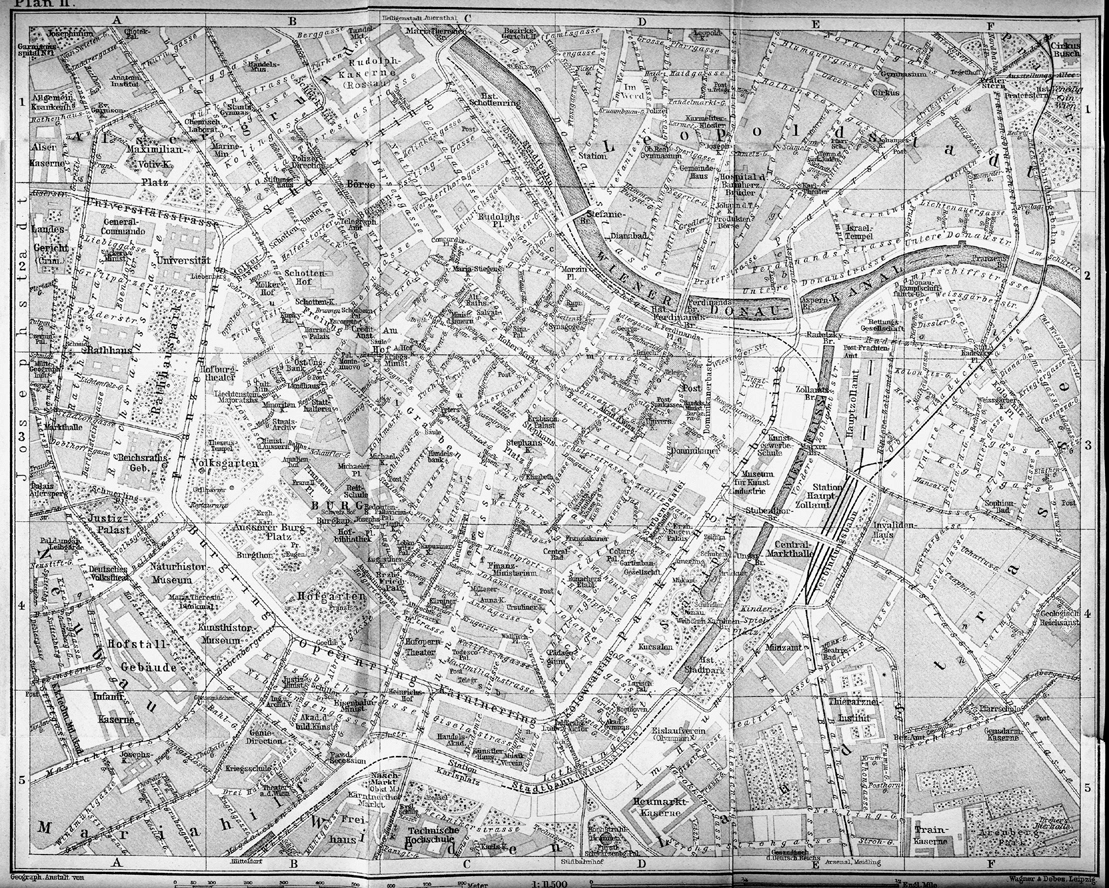

Plan of Vienna City Centre, 1905

Introduction: Falsehood in Wartime, by Edward Timms and Fred Bridgham

Preface, by Karl Kraus

Dramatis Personae

Prologue

Act I

Act II

Act III

Act IV

Act V

Epilogue: The Final Night

Translators’ Afterword and Acknowledgments

Glossary and Index

Map of European Battle Zones of the First World War

Plan of Vienna City Centre, 1905

INTRODUCTION: FALSEHOOD IN WARTIME

Edward Timms and Fred Bridgham

The early twentieth century was the great age of the newspaper press, as mass literacy endowed the printed word with unprecedented power. Newspaper production was revolutionized by rotary presses and linotype compositing machines, while modern roads and railways, together with the telephone, telegraph, and teleprinter, were transforming communications. In Western Europe and North America democratic institutions, social reforms, and scientific discoveries seemed to be laying the foundations for a new era in the history of mankind. But it was also a period of intense imperial rivalries, backed by highly trained forces and sophisticated armaments industries. Given the precarious international situation, it was possible at moments of crisis for journalists to tip the balance between peace and war. Liberal papers such as the Manchester Guardian (edited by C. P. Scott) and the New York Times (under Adolph Ochs) may have been committed to the peaceful resolution of conflicts, but wars were good for newspaper sales. Moreover, wealthy proprietors like Hearst and Northcliffe, Hugenberg and Benedikt, were imperialists capable of pressurizing governments into declarations of war.

Almost alone in the period before the First World War, the Viennese satirist Karl Kraus saw the press as an apocalyptic threat. In his magazine Die Fackel (The Torch), founded in April 1899, he would reprint prize examples of newspaper propaganda and expose their falsification of reality.1 His witty diatribes attracted a large readership, and with a print run of over 10,000 copies the magazine proved viable without having to rely on commercial advertising. To protect his independence Kraus created his own imprint, Verlag Die Fackel, which published book editions of his writings.

Where the editorials of the leading Austrian daily, the Neue Freie Presse, were celebrating the advances of German culture and the triumphs of European civilization, Kraus would expose the realities of conflict and suffering. He had a gift for dissecting the cliché-ridden language of his contemporaries. Sonorous metaphors like “standing shoulder to shoulder” evolved into satirical leitmotifs, culminating in his indictment of the anachronistic ideals that sustained the Central Powers during the First World War. His own style, by contrast, was enlivened by an aphoristic wit and moral fervour that left his readers uncertain whether to laugh or cry.

The apocalyptic tone of Kraus’s bleakest visions appeared to leave little hope for mankind. Borrowing from the Bible in a prophetic essay entitled “Apocalypse”, published in October 1908, he identified Kaiser Wilhelm II as an “apocalyptic horseman” with the power to destroy the peace of the earth.2 Moreover, the dangers arising from autocratic power were intensified by a technology that was running out of control: “ultimately, mankind lies dead beside the machines it has created, incapable of putting them to constructive use because so much intelligence has been expended on inventing them” (F 261–62, 1–5). This foreshadows the critique of mechanized warfare in Die Fackel of 1914–18, but it would be wrong to see Kraus’s satire as exclusively negative. It drew on a conception of human dignity shaped by the moral vision of Kant and the cultural ideals of Goethe. The satire of Die Fackel, which Kraus wrote single-handed from 1912 onwards, combined analyses of impending disaster with the advocacy of a better world.

Kraus was born on 28 April 1874 as the son of a prosperous Jewish paper manufacturer. Growing up in Vienna, he had to contend with the pressures of a deeply conservative and stridently anti-Semitic environment.

1 comment