The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

Like a King I Dined Attended by my Servants.

The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

Daniel Defoe

With Illustrations by

John Williamson

1873 Press

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United States by 1873 Press, New York.

1873 Press and colophon are trademarks of Barnes & Noble, Inc.

Book Design by Ericka O'Rourke, Elm Design

www.elmdesign.com

ISBN 0-594-05343-9

Contents

Chapter I

My birth and parentage—At nineteen years of age I determine to go to sea—Dissuaded by my parents—Elope with a schoolfellow, and go on board ship—A storm arises, during which I am dreadfully frightened—Ship founders—Myself and crew saved by a boat from another vessel, and landed near Yarmouth—Meet my companion's father there, who advises me never to go to sea more, but all in vain

Chapter II

Make a trading voyage to Guinea very successfully—Death of my captain—Sail another trip with his mate—The vengeance of Providence for disobedience to parents now overtakes me—Taken by a Sallee rover and all sold as slaves—My master frequently sends me a-fishing, which suggests an idea of escape—Make my escape in an open boat, with a Moresco boy

Chapter III

Make for the southward, in hope of meeting with some European vessel—See savages along shore—Shoot a large leopard—Am taken up by a merchantman—Arrive at the Brazils, and buy a settlement there—Cannot be quiet, but sail on a voyage of adventure to Guinea—Ship strikes on a sand-bank in unknown land—All lost but myself, who am driven ashore, half-dead

Chapter IV

Appearance of the wreck and country next day—Swim on board of the ship, and, by means of a contrivance, get a quantity of stores on shore—Shoot a bird, but it turns out perfect carrion—Moralize upon my situation—The ship blown off land, and totally lost—Set out in search of a proper place for a habitation—See numbers of goats—Melancholy reflections

Chapter V

I begin to keep a journal—Christen my desert island the Island of Despair—Fall upon various schemes to make tools, baskets, etc., and begin to build my house—At a great loss of an evening for candle, but fall upon an expedient to supply the want—Strange discovery of corn—A terrible earthquake and storm

Chapter VI

Observe the ship driven farther aground by the late storm—Procure a vast quantity of necessaries from the wreck—Catch a large turtle—I fall ill of a fever and ague—Terrible dream, and serious reflections thereupon—Find a bible in one of the seamen's chests thrown ashore, the reading whereof gives me great comfort

Chapter VII

I begin to take a survey of my island—Discover plenty of tobacco, grapes, lemons and sugar-canes, wild, but no human inhabitants—Resolve to lay up a store of these articles, to furnish me against the wet season—My cat, which I supposed lost, returns with kittens—I regulate my diet, and shut myself up for the wet season—Sow my grain, which comes to nothing; but I discover and remedy my error—Take account of the course of the weather

Chapter VIII

Make a second tour through the island—Catch a young parrot, which I afterwards teach to speak—My mode of sleeping at night—Find the other side of the island much more pleasant than mine, and covered with turtle and sea-fowl—Catch a young kid which I tame—Return to my old habitation—Great plague with my harvest

Chapter IX

I attempt to mould earthen-ware, and succeed—Description of my mode of baking—Begin to make a boat—After it is finished, am unable to get it down to the water—Serious reflections—My ink and biscuit exhausted, and clothes in a bad state—Contrive to make a dress of skins

Chapter X

I succeed in getting a canoe afloat, and set out on a voyage in the sixth year of my reign, or captivity—Blown out to sea—Reach the shore with great difficulty—Fall asleep, and am awakened by a voice calling my name—Devise various schemes to tame goats, and at last succeed

Chapter XI

Description of my figure—Also of my dwelling and enclosures—Dreadful alarm on seeing the print of a man's foot on the shore—Reflections—Take every possible measure of precaution

Chapter XII

I observe a canoe out at sea—Find on the shore the remnant of a feast of cannibals—Horror of mind thereon—Double arm myself—Terribly alarmed by a goat—Discover a singular cave or grotto, of which I form my magazine—My fears on account of the savages begin to subside

Chapter XIII

Description of my situation in the twenty-third year of my residence—Discover nine naked savages round a fire on my side of the island—My horror on beholding the dismal work they were about—I determine on the destruction of the next party, at all risks—A ship lost off the island—Go on board the wreck, which I discern to be Spanish—Procure a great variety of articles from the vessel

Chapter XIV

Reflections—An extraordinary dream—Discover five canoes of savages on shore—Observe from my station two miserable wretches dragged out of their boats to be devoured—One of them makes his escape, and runs directly towards me, pursued by two others—I take measures so as to destroy his pursuers, and save his life—Christen him by the name of Friday, and he becomes a faithful and excellent servant

Chapter XV

I am at great pains to instruct Friday respecting my abhorrence of the cannibal practices of the savages—He is amazed at the effects of the gun, and considers it an intelligent being—Begins to talk English tolerably—A dialogue—I instruct him in the knowledge of religion, and find him very apt—He describes to me some white men who had come to his country, and still lived there

Chapter XVI

I determine to go over to the continent—Friday and I construct a boat equal to carry twenty men—His dexterity in managing her—Friday brings intelligence of three canoes of savages on shore—Resolve to go down upon them—Friday and I fire upon the wretches, and save the life of a poor Spaniard—List of the killed and wounded—Discover a poor Indian bound in one of the canoes, who turns out to be Friday's father

Chapter XVII

I learn from the Spaniard that there were sixteen more of his countrymen among the savages—The Spaniard and Friday's father, well-armed, sail on a mission to the Continent—I discover an English ship lying at anchor off the island—Her boat comes on shore with three prisoners—The crew straggle into the woods, their boat being aground—Discover myself to the prisoners, who prove to be the captain and mate of the vessel, and a passenger—Secure the mutineers

Chapter XVIII

The ship makes signals for her boat—On receiving no answer, she sends another boat on shore—Methods by which we secure this boat's crew, and recover the ship

Chapter XIX

I make inquiries about my family—I receive a present of money—I go over to Lisbon with Friday—I find my trustees dead, but as my partner in the Brazils has acted honestly, the estate is increased in value, and yields comfortable returns—Returning overland to England, Friday has an adventure with a bear—We are attacked by wolves—I take to myself a wife—Some years after I visit my property in the Brazils

List of Illustrations

Like a King I Dined Attended by my Servants

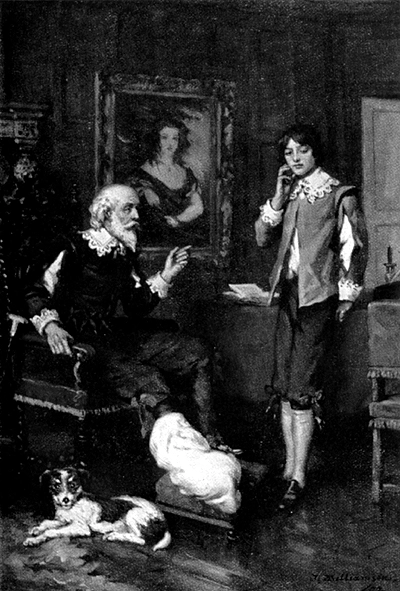

My Father Gave me Serious and Excellent Counsel

With this Cargo I Put to Sea

I Gathered a Great Heap of Grapes in One Place and a Great Parcel of Limes and Lemons in Another

They were Dancing Round the Fire

Friday's Rescue from the Cannibals

There Happened a Fierce Engagement between the Spaniard and one of the Savages

The Mutineers Calling to their Mates

The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

Chapter I

I WAS born, in the year 1632, in the city of York, of a good family, though not of that country, my father being a foreigner of Bremen, who settled first at Hull. He got a good estate by merchandise, and, leaving off his trade, lived afterwards at York, from whence he had married my mother, whose relations were named Robinson, a very good family in that country, and from whom I was called Robinson Kreutznaer; but, by the usual corruption of words in England, we are now called—nay, we call ourselves, and write our name—Crusoe; and so my companions always called me.

I had two elder brothers, one of which was a lieutenant-colonel to an English regiment of foot in Flanders, formerly commanded by the famous Colonel Lockhart, and was killed at the battle near Dunkirk against the Spaniards; what became of my second brother, I never knew, any more than my father or mother did know what was become of me.

Being the third son of the family, and not bred to any trade, my head began to be filled very early with rambling thoughts. My father, who was very ancient, had given me a competent share of learning, as far as house educators and a country free school generally go, and designed me for the law; but I would be satisfied with nothing but going to sea; and my inclination to this led me so strongly against the will—nay, the commands—of my father, and against all the entreaties and persuasions of my mother and other friends, that there seemed to be something fatal in that propension of nature, tending directly to the life of misery which was to befall me.

My Father Gave Me Serious and Excellent Counsel.

My father, a wise and grave man, gave me serious and excellent counsel against what he foresaw was my design. He called me one morning into his chamber, where he was confined by the gout, and expostulated very warmly with me upon this subject. He asked me what reasons, more than a mere wandering inclination, I had for leaving my father's house and my native country, where I might be well introduced, and had a prospect of raising my fortune by application and industry, with a life of ease and pleasure. He told me it was only men of desperate fortunes on one hand, or of aspiring superior fortunes on the other, who went abroad upon adventures, to rise by enterprise, and make themselves famous in undertakings of a nature out of the common road; that these things were all either too far above me, or too far below me; that mine was the middle state, or what it might be called the upper station of low life, which he had found, by long experience, was the best state in the world—the most suited to human happiness, not exposed to the miseries and hardships, the labour and sufferings, of the mechanic part of mankind, and not embarrassed with the pride, luxury, ambition, and envy, of the upper part of mankind. He told me, I might judge of the happiness of this state, by this one thing, namely, that this was the state of life which all other people envied; that kings have frequently lamented the miserable consequences of being born to great things, and wished they had been placed in the middle of the two extremes, between the mean and the great; that the wise man gave his testimony to this, as the just standard of true felicity, when he prayed to have neither poverty nor riches.

He bade me observe it, and I should always find, that the calamities of life were shared among the upper and lower part of mankind; but that the middle station had the fewest disasters, and was not exposed to so many vicissitudes as the higher or lower part of mankind; nay, they were not subjected to so many distempers and uneasiness, either of body or mind, as those were who, by vicious living, luxury, and extravagances, on one hand, or by hard labour, want of necessaries, and mean or insufficient diet, on the other hand, bring distempers upon themselves by the natural consequences of their way of living; that the middle station of life was calculated for all kind of virtues, and all kind of enjoyments; that peace and plenty were the handmaids of a middle fortune; that temperance, moderation, quietness, health, society, all agreeable diversions, and all desirable pleasures, were the blessings attending the middle station of life; that this way men went silently and smoothly through the world, and comfortably out of it; not embarrassed with the labours of the hands or of the head; not sold to a life of slavery for daily bread, or harassed with perplexed circumstances, which rob the soul of peace and the body of rest; not enraged with the passion of envy, or the secret burning lust of ambition for great things—but in easy circumstances, sliding gently through the world, and sensibly tasting the sweets of living without the bitter; feeling that they are happy, and learning, by every day's experience, to know it more sensibly.

After this he pressed me earnestly, and in the most affectionate manner, not to play the young man, or to precipitate myself into miseries, which nature, and the station of life I was born in, seemed to have provided against—that I was under no necessity of seeking my bread—that he would do well for me, and endeavour to enter me fairly into the station of life which he had been just recommending to me; and that, if I was not very easy and happy in the world, it must be my mere fate, or fault, that must hinder it; and that he should have nothing to answer for, having thus discharged his duty, in warning me against measures which he knew would be to my hurt. In a word, that as he would do very kind things for me, if I would stay and settle at home as he directed, so he would not have so much hand in my misfortunes as to give me any encouragement to go away—and, to close all, he told me, I had my elder brother for my example, to whom he had used the same earnest persuasions to keep him from going into the Low Country wars, but could not prevail, his young desires prompting him to run into the army, where he was killed—and though he said he would not cease to pray for me, yet he would venture to say to me, that if I did take this foolish step, God would not bless me—and I would have leisure hereafter to reflect upon having neglected his counsel, when there might be none to assist in my recovery.

I observed, in this last part of his discourse, which was truly prophetic, though I suppose my father did not know it to be so himself—I say, I observed the tears run down his face very plentifully, especially when he spoke of my brother who was killed; and that when he spoke of my having leisure to repent, and none to assist me, he was so moved, that he broke off the discourse, and told me, his heart was so full he could say no more to me.

I was sincerely afflicted with this discourse—as, indeed, who could be otherwise?—and I resolved not to think of going abroad any more, but to settle at home according to my father's desire. But, alas! a few days wore it all off; and, in short, to prevent any of my father's further importunities, in a few weeks after, I resolved to run quite away from him. However, I did not act so hastily neither, as the first heat of my resolution prompted, but I took my mother at a time when I thought her a little pleasanter than ordinary, and told her, that my thoughts were so entirely bent upon seeing the world, that I should never settle to any thing with resolution enough to go through with it, and my father had better give me his consent, than force me to go without it—that I was now eighteen years old, which was too late to go apprentice to a trade, or clerk to an attorney—that I was sure, if I did, I should never serve out my time, but I should certainly run away from my master before my time was out, and go to sea—and if she would speak to my father to let me go one voyage abroad, if I came home again, and did not like it, I would go no more, and I would promise, by a double diligence, to recover the time I had lost.

This put my mother into a great passion; she told me she knew it would be to no purpose to speak to my father upon any such subject—that he knew too well what was my interest, to give his consent to any such thing so much for my hurt—and that she wondered how I could think of any such thing, after the discourse I had had with my father, and such kind and tender expressions as she knew my father had used to me—and that, in short, if I would ruin myself, there was no help for me; but I might depend I should never have their consent to it—that, for her part, she would not have so much hand in my destruction—and I should never have it to say, that my mother was willing when my father was not.

Though my mother refused to move it to my father, yet I heard afterwards, that she reported all the discourse to him; and that my father, after shewing a great concern at it, said to her, with a sigh, "That boy might be happy if he would stay at home; but if he goes abroad, he will be the most miserable wretch that ever was born—I can give no consent to it."

It was not till almost a year after this that I broke loose, though in the meantime I continued obstinately deaf to all proposals of settling to business, and frequently expostulating with my father and mother about their being so positively determined against what they knew my inclinations prompted me to. But being one day at Hull, whither I went casually, and without any purpose of making an elopement that time—but, I say, being there, and one of my companions being going by sea to London, in his father's ship, and prompting me to go with him, with the common allurement of a sea-faring man, that it should cost me nothing for my passage, I consulted neither father nor mother any more, nor so much as sent them word of it; but leaving them to hear of it as they might, without asking God's blessing or my father's, without any consideration of circumstances or consequences, and, in an ill hour, God knows, on the 1st of September 1651, I went on board a ship bound for London. Never any young adventurer's misfortunes, I believe, began sooner, or continued longer, than mine. The ship was no sooner got out of the Humber, but the wind began to blow, and the sea to rise in a most frightful manner; and as I had never been at sea before, I was most inexpressibly sick in body, and terrified in mind. I began now seriously to reflect upon what I had done, and how justly I was overtaken by the judgment of Heaven for my wicked leaving my father's house, and abandoning my duty; all the good counsel of my parents, my father's tears and my mother's entreaties, came now fresh into my mind; and my conscience, which was not yet come to the pitch of hardness to which it has been since, reproached me with the contempt of advice, and the breach of my duty to God and my father.

All this while the storm increased, and the sea went very high, though nothing like what I have seen many times since—no, nor what I saw a few days after; but it was enough to affect me then, who was but a young sailor, and had never known anything of the matter. I expected every wave would have swallowed us up, and that every time the ship fell down, as I thought it did, in the trough or hollow of the sea, we should never rise more. In this agony of mind, I made many vows and resolutions, that if it would please God to spare my life in this one voyage, if ever I got once my foot upon dry land again, I would go directly home to my father, and never set it into a ship again while I lived; but I would take his advice, and never run myself into such miseries as these any more. Now I saw plainly the goodness of his observations about the middle station of life, how easy, how comfortable, he had lived all his days, and never had been exposed to tempests at sea, nor trouble on shore; and, in short, I resolved that I would, like a true repenting prodigal, go home to my father.

These wise and sober thoughts continued all the while the storm continued, and indeed some time after; but the next day the wind was abated, and the sea calmer, and I began to be a little inured to it. However, I was very grave for all that day, being also a little sea-sick still; but towards night the weather cleared up, the wind was quite over, and a charming fine evening followed; the sun went down perfectly clear, and rose so the next morning; and having little or no wind, and a smooth sea, the sun shining upon it, the sight was, as I thought, the most delightful that ever I saw.

I had slept well in the night, and was now no more sea-sick, but very cheerful—looking with wonder upon the sea, that was so rough and terrible the day before, and could be so calm and so pleasant in so little a time after; and now, lest my good resolutions should continue, my companion, who had indeed enticed me away, comes to me. "Well, Bob," says he, clapping me upon the shoulder, "how do you do after it? I warrant you were frightened, weren't you, last night, when it blew but a capful of wind?" "A capful d'ye call it?" said I, "'twas a terrible storm." "A storm, you fool you!" replies he, "do you call that a storm? why it was nothing at all; give us but a good ship and sea-room, and we think nothing of such a squall of wind as that; but you're but a fresh-water sailor, Bob; come, let us make a bowl of punch, and we'll forget all that: d'ye see what charming weather 'tis now?" To make short this sad part of my story, we went the way of all sailors; the punch was made, and I was made half drunk with it, and in that one night's wickedness I drowned all my repentance, all my reflections upon my past conduct, all my resolutions for the future. In a word, as the sea was returned to its smoothness of surface, and settled calmness, by the abatement of that storm, so, the hurry of my thoughts being over, my fears and apprehensions of being swallowed up by the sea being forgotten, and the current of my former desires returned, I entirely forgot the vows and promises that I made in my distress. I found, indeed, some intervals of reflection; and the serious thoughts did, as it were, endeavour to return again sometimes; but I shook them off, and roused myself from them, as it were from a distemper; and, applying myself to drinking and company, soon mastered the return of those fits (for so I called them); and I had, in five or six days, got a complete victory over my conscience, as any young fellow that resolved not to be troubled with it could desire. But I was to have another trial for it still; and Providence, as in such cases generally it does, resolved to leave me entirely without excuse; for if I would not take this for a deliverance, the next was to be such an one, as the worst and most hardened wretch among us would confess both the danger and the mercy.

The sixth day of our being at sea, we came into Yarmouth roads; the wind having been contrary and the weather calm, we had made but little way since the storm. Here we were obliged to come to an anchor, and here we lay, the wind continuing contrary, namely, at south-west, for seven or eight days; during which time, a great many ships from Newcastle came into the same roads, as the common harbour where the ships might wait for a wind for the river.

We had not, however, rid here so long, but we should have tided it up the river, but that the wind blew too fresh; and after we had lain four or five days, blew very hard. However, the roads being reckoned as good as a harbour, the anchorage good, and our ground-tackle very strong, our men were unconcerned, and not in the least apprehensive of danger, but spent the time in rest and mirth, after the manner of the sea; but the eighth day in the morning, the wind increased, and we had all hands at work to strike our topmasts, and make every thing snug and close, that the ship might ride as easy as possible. By noon, the sea went very high indeed, and our ship rid forecastle in, shipped several seas, and we thought once or twice our anchor had come home; upon which our master ordered out the sheet anchor; so that we rode with two anchors a-head, and the cables veered out to the better end.

By this time, it blew a terrible storm indeed; and now, I began to see terror and amazement in the faces even of the seamen themselves. The master, though vigilant in the business of preserving the ship, yet as he went in and out of his cabin by me, I could hear him, softly to himself, say several times, "Lord be merciful to us! we shall be all lost—we shall be all undone!" and the like. During these first hurries, I was stupid, lying still in my cabin, which was in the steerage, and cannot describe my temper. I could ill resume the first penitence which I had so apparently trampled upon, and hardened myself against; I thought the bitterness of death had been past; and that this would be nothing, too, like the first. But when the master himself came by me, as I said just now, and said we should be all lost, I was dreadfully frighted: I got up out of my cabin and looked out; but such a dismal sight I never saw: the sea went mountains high, and broke upon us every three or four minutes; when I could look about, I could see nothing but distress round us. Two ships that rid near us, we found, had cut their masts by the board, being deep laden; and our men cried out, that a ship, which rid about a mile a-head of us, was foundered.

1 comment