The Lincoln Letter

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR CHRIS

I could have dedicated all my books to her.

And in some way, I have.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

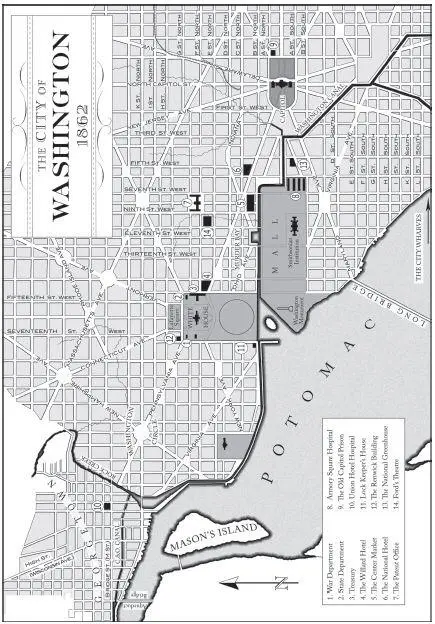

Map of the City of Washington, 1862

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Acknowledgments

Books by William Martin

Copyright

PROLOGUE

April 1865

On the last day of his life, Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter.

If he was angry, anger did not reveal itself in his handwriting, which was typically clean and open. If he was euphoric, and those who observed him that day attested later that he was, euphoria did not express itself either.

The letter lacked the poetry of his best speeches and demonstrated none of the cold and relentless logic of his political writing.

It was as simple, direct, and blunt as a cannonball:

Dear Lieutenant Hutchinson,

It comes to my attention that you are still alive. This means that you may still be in possession of something that I believe fell into your hands in the telegraph office three years ago. It would be best if you returned it, considering its potential to alter opinions regarding the difficulties just ended and those that lie ahead. If you do, a presidential pardon will be considered.

A. Lincoln.

Lincoln did not inform his secretary about the letter.

It was unlikely that he wanted questions regarding correspondence with an officer who had served not only in the field but also in the War Department telegraph office, before coming into significant personal difficulty.

It would also have appeared strange that Lincoln did not address the letter to Lieutenant Hutchinson. He sent it instead to Corporal Jeremiah Murphy at the Armory Square Hospital on Seventh Street.

But even a president had his secrets.

Lincoln sealed the letter and slipped it into a pile of outgoing correspondence, some to be mailed, some to be hand delivered around the city.

It was just after eight when his wife appeared in the doorway to his office. She was wearing a white dress with black stripes and a bonnet adorned with pink silk flowers. She had always favored flowers. But she had worn them less and less in the last four years. No woman who had lost a son and two half brothers, no woman who had watched her husband grow old under history’s heaviest burden, would be inclined to wear anything but black. Still, flowers and dress did nothing to soften her voice. “Mr. Lincoln, would you have us be late?”

He said, “Tonight, we shall laugh.”

Then he called for his carriage, and they went to the theater.

ONE

Friday Night

Peter Fallon received a copy of that letter as an attachment to an e-mail on the third Friday night of September.

He would not have read it, except that it came from Diana Wilmington, an assistant professor at the George Washington University and author of a controversial new book, The Racism and Resolve of Abraham Lincoln. The book had gotten her onto television, radio, magazine covers, and made her one of the most recognizable African American scholars in the country. Peter had also dated her when she was an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts.

“I’ve been thinking of you,” she wrote. “I still read the Boston gossip pages. (How could I not, after the gossip we inspired?) So that bit about you and Evangeline caught my eye. Not getting married but still having a reception … genius.”

Yes, thought Peter. Genius. The hall had been rented and the champagne was cold. It was a great party. As for the decision not to get married … he was not so sure.

He took a sip of wine and kept reading:

“I really liked Evangeline. I thought she was good for you.”

True. Peter couldn’t remember which of them first said, “If it works don’t fix it.” But now, Evangeline was prepping a new project in New York, and Peter was guest-curating a new exhibit in Boston.

“However,” Diana went on, “I’m not writing about your love life. I’d like you to take a look at this attachment.”

Peter clicked to the scanned image of a letter. He glanced first at the header, printed in an Old English typeface: “Executive Mansion.” Beneath it was the word “Washington,” the date April 14, 1865, and to the side, the word “Private” handwritten and circled. Then Peter’s eye dropped to the signature, to the clear and characteristic cursive that was the Holy Grail of autograph collectors everywhere: A.

1 comment