In summer he taught the children croquet on his lawn, and rigged up a small gym in the bam. He took them on nature rambles through the woods and down to the river to swim. And when the winter snows and ice came, there was no end to the games the children played: speeding downhill on great sleds, snowballing, tumbling in the snow — with the Count himself in the thick of them! They cleared the snow from the big lake to make a skating rink; they held races there, but few could beat Tolstoy, who was an excellent skater.

At Christmastime he decorated a big fir tree inside his house and held a party for all the children on his estate. Of course, the thin ragged village children had never had such a party in their lives.

In those days children’s lives were hard. As soon as they were strong enough — about the age of ten — they had to drive a wooden plow and toil in the fields from dawn to dusk. Childhood ended early in Russia at that time; peasant families were but serfs, slaves to the lords.

Yet here was a lord, Count Tolstoy, who was opening the doors of his house, with its polished wooden floors, lofty ceilings, and bright windows, to the village children. It all seemed a fairy tale.

But it was real enough. And so was their teacher’s love for them. Throughout his long life Tolstoy loved children. It hurt him to see so much poverty and ignorance among the children in the countryside. But he also knew how miserable the lives of the children in the towns were. His heart ached at the sound of the factory whistles at dawn and dusk from the mill beyond the village. He once visited that mill and wrote in his diary:

I visited a stocking mill and learned what the whistles mean. At five o’ clock in the morning a boy takes his stand beside a machine and stays there till eight. At eight he drinks tea and then stands till midday; and at one he begins again and stands till four; then he works through from half past four to eight in the evening. Every day, seven days a week. That’s what the whistles mean we hear in our beds.

He wondered how such children had time to live, children whom whistles set in motion at five in the morning and stopped at eight in the evening. When would they learn, read books, have time to play?

Tolstoy’s school was the first in Russia for village children. But when he came to seek school books that were easy to read and interesting he was disappointed. What few children’s books existed were dull and more likely to put out the spark of interest than kindle it.

So the great writer, known throughout the world for his famous books, sat down to write stories for children that were easy to read and interesting, that would teach right from wrong, good from bad. Even though his great works took up much of his time and energy, he always found time for the children.

The stories he wrote were not only for the village children around Clear Glades. They were intended for all girls and boys who wish to open up their hearts to truth and beauty.

TRANSLATORS NOTE

The stories are taken from Tolstoy’s Azbuka (Primer) which consisted of four “Russian Reading Books,” four “Slav Reading Books,” a section on teaching reading, handwriting, and arithmetic, and guidance for teachers. Although the Primer was not published until 1872, it was based on notebooks Tolstoy had kept from his first teaching experience at his school for peasant children at Yasnaya Polyana (Clear Glades) from 1849 and at other schools he founded for peasant children in the Tula Province.

The stories vary widely: some are based on Aesop’s fables, others on Russian and foreign folk tales, some on nature studies, and others on the work of children themselves. As an example of the latter, the “Young Boy’s Stories” all come from the storytelling of peasant children whom Tolstoy encouraged to read and write “in their own words.“

What distinguishes all the stories in the Primer from children’s stories current in Russian schools at that time is that they are largely free from the heavy moralistic homilies and religious preaching that Tolstoy abhorred. Moreover, they are written in a simple language style “for a new audience,” as Tolstoy put it, “that has to be counted in many thousands, even millions“

The present versions are taken from Novaya azbuka (New Primer) and the four Russkie knigi dlya chteniya (Russian Reading Books) edited by Tolstoy for the 1875 edition. They are contained in L. N. Tolstoy Sobranie sochineniy v 14 tomkakh, torn desyaty (Collected Works in 14 Vol-u mes, vol 10), Moscow, 1952.

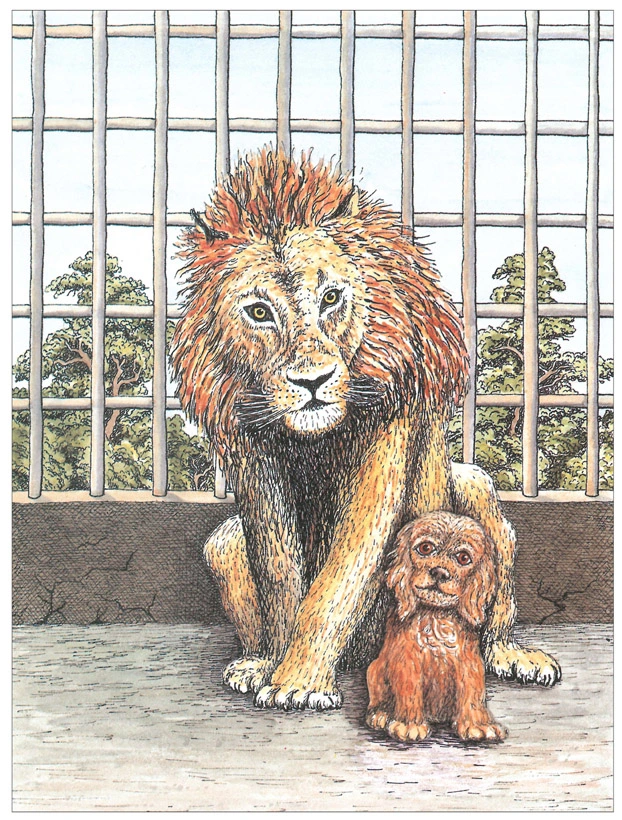

THE LION AND THE PUPPY

There was once a zoo in London that took stray cats and dogs to feed its wild animals. One time, a visitor to the zoo picked up a puppy from the street and took it along with him. Handing it over at the gate, he watched the keeper throw the hapless puppy into the lion’s cage.

Poor little dog.

Tail between its legs, it squeezed itself into the corner of the cage as the lion came closer and closer.

Suddenly the lion stopped and began to sniff his victim.

1 comment