It hurt him to see so much poverty and ignorance among the children in the countryside. But he also knew how miserable the lives of the children in the towns were. His heart ached at the sound of the factory whistles at dawn and dusk from the mill beyond the village. He once visited that mill and wrote in his diary:

I visited a stocking mill and learned what the whistles mean. At five o’ clock in the morning a boy takes his stand beside a machine and stays there till eight. At eight he drinks tea and then stands till midday; and at one he begins again and stands till four; then he works through from half past four to eight in the evening. Every day, seven days a week. That’s what the whistles mean we hear in our beds.

He wondered how such children had time to live, children whom whistles set in motion at five in the morning and stopped at eight in the evening. When would they learn, read books, have time to play?

Tolstoy’s school was the first in Russia for village children. But when he came to seek school books that were easy to read and interesting he was disappointed. What few children’s books existed were dull and more likely to put out the spark of interest than kindle it.

So the great writer, known throughout the world for his famous books, sat down to write stories for children that were easy to read and interesting, that would teach right from wrong, good from bad. Even though his great works took up much of his time and energy, he always found time for the children.

The stories he wrote were not only for the village children around Clear Glades. They were intended for all girls and boys who wish to open up their hearts to truth and beauty.

TRANSLATORS NOTE

The stories are taken from Tolstoy’s Azbuka (Primer) which consisted of four “Russian Reading Books,” four “Slav Reading Books,” a section on teaching reading, handwriting, and arithmetic, and guidance for teachers. Although the Primer was not published until 1872, it was based on notebooks Tolstoy had kept from his first teaching experience at his school for peasant children at Yasnaya Polyana (Clear Glades) from 1849 and at other schools he founded for peasant children in the Tula Province.

The stories vary widely: some are based on Aesop’s fables, others on Russian and foreign folk tales, some on nature studies, and others on the work of children themselves. As an example of the latter, the “Young Boy’s Stories” all come from the storytelling of peasant children whom Tolstoy encouraged to read and write “in their own words.“

What distinguishes all the stories in the Primer from children’s stories current in Russian schools at that time is that they are largely free from the heavy moralistic homilies and religious preaching that Tolstoy abhorred. Moreover, they are written in a simple language style “for a new audience,” as Tolstoy put it, “that has to be counted in many thousands, even millions“

The present versions are taken from Novaya azbuka (New Primer) and the four Russkie knigi dlya chteniya (Russian Reading Books) edited by Tolstoy for the 1875 edition. They are contained in L. N. Tolstoy Sobranie sochineniy v 14 tomkakh, torn desyaty (Collected Works in 14 Vol-u mes, vol 10), Moscow, 1952.

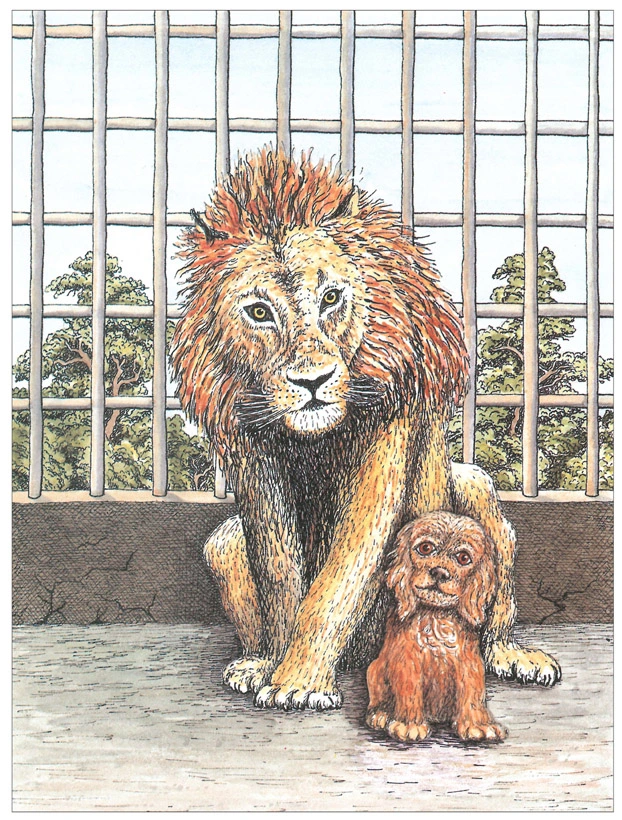

THE LION AND THE PUPPY

There was once a zoo in London that took stray cats and dogs to feed its wild animals. One time, a visitor to the zoo picked up a puppy from the street and took it along with him. Handing it over at the gate, he watched the keeper throw the hapless puppy into the lion’s cage.

Poor little dog.

Tail between its legs, it squeezed itself into the corner of the cage as the lion came closer and closer.

Suddenly the lion stopped and began to sniff his victim. Tickled by the lion’s whiskers, the puppy rolled over and wagged its tail playfully At that, the lion prodded it uncertainly with his paw, pushing it to and fro over the floor of his cage.

To the lion’s surprise, the little dog nimbly jumped up and stood on its hind legs, begging.

Puzzled, the lion stared at the dog, shifting his massive head slowly from side to side, not knowing what to make of this funny little animal.

But he let it be.

At feeding time, when the keeper tossed meat into the cage, the lion tore off a piece for the puppy And at sunset, as the lion lay down to sleep, the puppy lay alongside him, resting its tiny head on the lion’s great paws.

From that day on the lion and the puppy lived together in the same cage: the lion sharing his food, never harming his companion, sleeping alongside and, now and then, playing with it.

Then, one day, a fine gentleman visited the zoo and straightaway recognized his long-lost pet. The keeper was informed and, of course, would willingly have handed it over had not the lion raged and roared every time he approached the puppy in the end he gave up and the gentleman had to go home empty-handed.

So the lion and the puppy stayed together; thus it continued for a whole year, until one day the little dog fell sick. And in a short space of time it died.

What a change came over the lion! All the while he licked and sniffed his friend, prodding it with his paw. At last, realizing it was indeed dead, the lion sprang up, his mane quivering with rage. He stalked about the cage, swinging his tail fiercely He flung himself against the iron bars and tore at the wooden floorboards.

All day long he roared in his anguish until finally he sank down beside his dead companion. And he was quiet.

But when the keeper tried to remove the dead puppy, the lion growled menacingly and would not let him near. After a while, the keeper had an idea. Thinking a new puppy would make the lion forget his grief, he thrust another dog between the bars.

But the lion ignored the puppy.

Then, gently, he put his paws about his cold little friend and lay grieving for a full five days.

And on the sixth day the lion died.

LITTLE COTTONTOP

There was once an old man and old woman. One day the old man went off to the fields to plow, while the old woman stayed home to make pancakes.

1 comment