The boy was frightened and would have fled had not his master pulled him after the bear.

Old Bruno bellowed even more fearfully and lumbered off into the trees. Clearly, it was foolhardy to pursue him into the depths of the forest where they might encounter more bears or even wolves. But the master had an idea.

“Put on the goat’s mask and bang your drum,” he told the boy

At the same time he shouted gruffly to the bear, just as he did when he was showing him off, “Dance, Bruno, dance!”

All of a sudden the bear stopped in his tracks, stood up on his hind legs, and began to twirl around slowly. In the meantime, his wily master crept closer, shouting and calling, “Dance, Bruno, dance!”

His assistant all the while clowned before the bear, beating the drum and singing. When the master was quite near, he lunged forward to grab the chain. The bear saw the ruse too late, roared helplessly, and tried to escape. But the master clung on tightly.

And that was how Old Bruno came to be recaptured. Once again he was led round the fairs and inns, forever twirling, clowning, and dancing in his chains.

For people’s amusement.

MASHA AND THE MUSHROOMS

Two little sisters were walking home from gathering mushrooms when they came to a railway track. Thinking no train was near, they climbed over a rail and were crossing the line when, from out of nowhere, a great locomotive whistled shrilly.

The two little girls were scared out of their wits. As the bigger girl held back, her little sister dashed forward to the middle of the track.

“Masha, Masha!” cried her sister. “Go on, go on. Cross the track quickly.”

But the train made such a clattering as it approached that Masha did not hear; she thought she was being called back. And as she turned, the poor girl stumbled and fell, scattering the mushrooms from her basket all over the railway track.

In a panic, the girl tried quickly to gather them up.

The train was now quite near. Its driver hollered and pulled the whistle for all he was worth, and in the meantime Masha’s sister was screaming frantically to her:

“Leave the mushrooms! Oh, let them be!“

Through the din, however, the little girl heard only “the mushrooms” and, thinking her sister had said to pick them up, she was crawling along the track on hands and knees, picking up her scattered mushrooms.

The train was now bearing down on hen . . . There was nothing anyone could do. And, with one despairing whistle, the great monster was upon her.

Masha’s sister could not bear to look: she hid her head in her hands in horror. Ashen-faced, the train’s passengers stared dumbly from the windows, while the guard peered back along the track to see what had become of the poor girl.

There she was, face pressed to the ground, lying motionless between the rails. And then, as the train rumbled on its way, she suddenly lifted her head, picked up the rest of her mushrooms, and ran off, unharmed, to her sister.

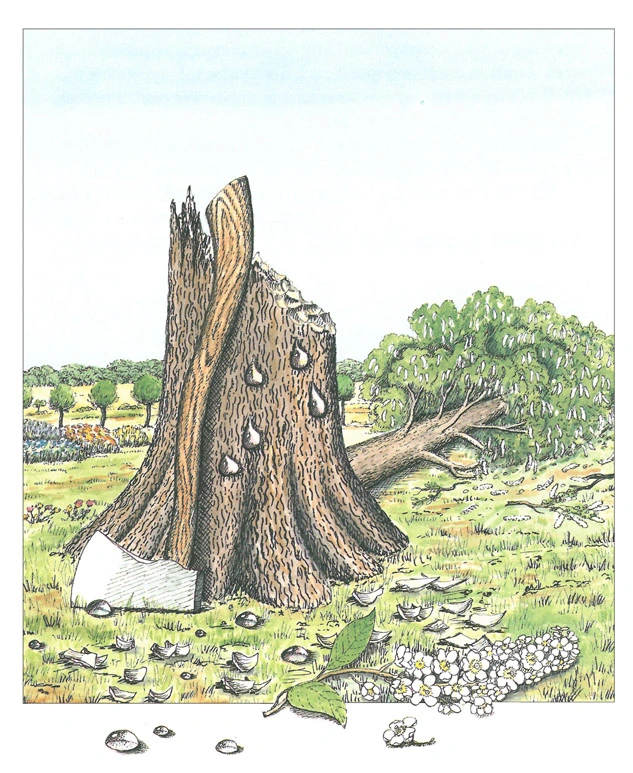

DEATH OF A BIRD-CHERRY TREE

A bird-cherry had grown wild beside the path to the nut grove and was blocking out the sunlight from our young hazel trees. For a long time I pondered over it: Should I or should I not cut down the tree?

It seemed a shame to kill such a beautiful thing.

The bird-cherry was more of a tree than a bush, some three feet in girth and twelve feet high, all gnarled and forked, and graced with a white sweet-scented blossom whose fragrance wafted even as far as the house.

I would surely have let it live had not one of my woodmen begun the job one morning. No doubt I had told him sometime earlier to grub out all the bird-cherry

When I came on the scene his axe had already bitten a good foot out of the trunk; and the sap was squealing its complaint at each blow of the axe.

“Oh, well, perhaps it’s all for the good,” I sighed, taking up an axe and lending a hand.

With the chips flying about and the sweet smell of freshly hewn wood in my nostrils, all my doubts about the bird-cherry vanished. My mind was now set on felling the tree. And when we laid aside our axes and put our shoulders to the tree, trying to push it over, I felt a sense of triumph course through my veins. We heaved hard: the leaves trembled, showering us with dewdrops and little white bouquets of petals.

And then an unnerving sound came from inside the very soul of that tree. It was as if someone was screaming in unbearable pain, a tearing, wrenching, long drawn-out scream.

Gripped by a mixture of fear and sorrow, we hastily gave a last heave and, with a heartrending, sobbing sigh, the tree shuddered and fell.

After the first crash, the branches and blossoms lay trembling for a while, then lay still. For several moments, the woodman and I stood silent, unable to speak. Then, in the awkward hush, my companion muttered:

“Whew, she don’t die easy, Sir!“

A lump in my throat blocked my words, and I turned quickly to make my way back to the house. I did not dare glance back.

LITTLE PHILIP WHO WANTED

TO GO TO SCHOOL

Philip was too young to go to school’ But when, at the end of the summer holidays, the older children went off to school, Philip got ready to go too.

His mother was surprised.

“Where are you going, Philip?”

“To school”

“But you’re still too young,” she said with a smile.

His playmates were all in school Father had gone off early that morning to work. And now mother had gone out shopping.

1 comment