Thinking there must be someone left in the building, the firemen let him go.

Bounding through the flames and smoke, the dog soon reappeared with another bundle in his teeth. The crowd gathered around in silence to take a closer look. Then smiles gradually spread over all the faces.

For the old fire-dog was carrying a big rag doll.

TWO MERCHANTS

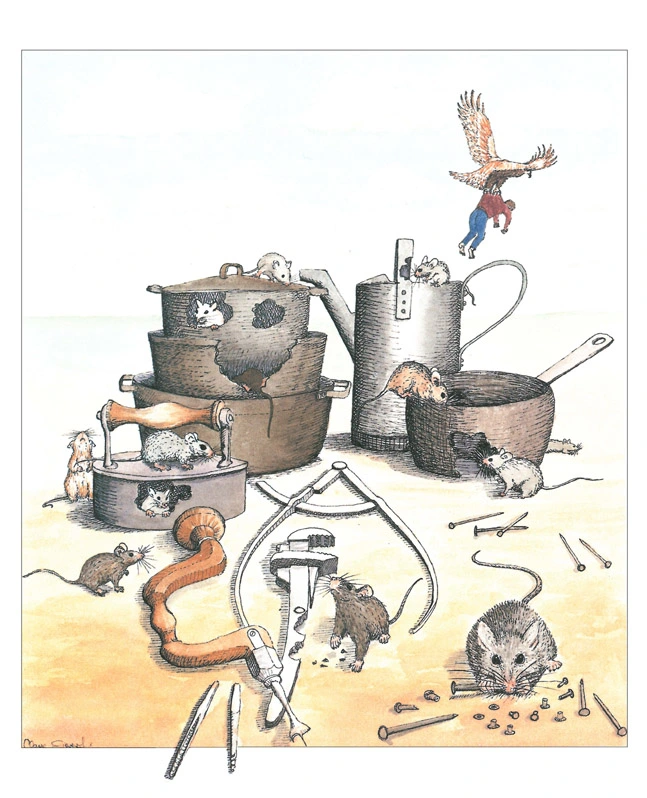

A poor merchant once went on his travels, leaving all his iron merchandise with a rich merchant for safekeeping. When he returned, he went to the wealthy merchant and asked for his ironwares back.

But the wealthy merchant had already sold them and now had to make his excuses.

“I’m sorry to say that your iron is all gone.”

“What happened?”

“It’s like this: I stored your wares in my barn, and the mice came and ate them. They finished off the whole lot. I myself saw them nibbling at it. Go and see if you don’t believe me.”

The poor merchant did not bother to argue. He simply said:

“What is there to see? I believe you. I know mice are always eating iron.”

And the poor merchant went off.

Once outside, he saw the rich merchant’s son playing in the yard, and he persuaded the boy to come along with him.

Next day the wealthy merchant met the poor man and told him of his misfortune. His son had disappeared. Had he not seen or heard anything?

To which the poor merchant said, “Now that you ask, I did see something. I was just leaving your house yesterday when a hawk flew down and snatched up your son.”

The wealthy merchant flew into a rage, crying, “How dare you make fun of me. Everybody knows hawks don’t carry off children.”

Tut I’m not making fun of you,” said the poor man. “Why should a hawk not carry off a boy, when mice can eat a hundred pounds of iron?”

At that the wealthy merchant understood.

“Mice did not eat your iron,” he said. “I sold it and will pay you double.”

“In that case, a hawk did not carry off your son,” replied the other. “I’ll bring him back at once.”

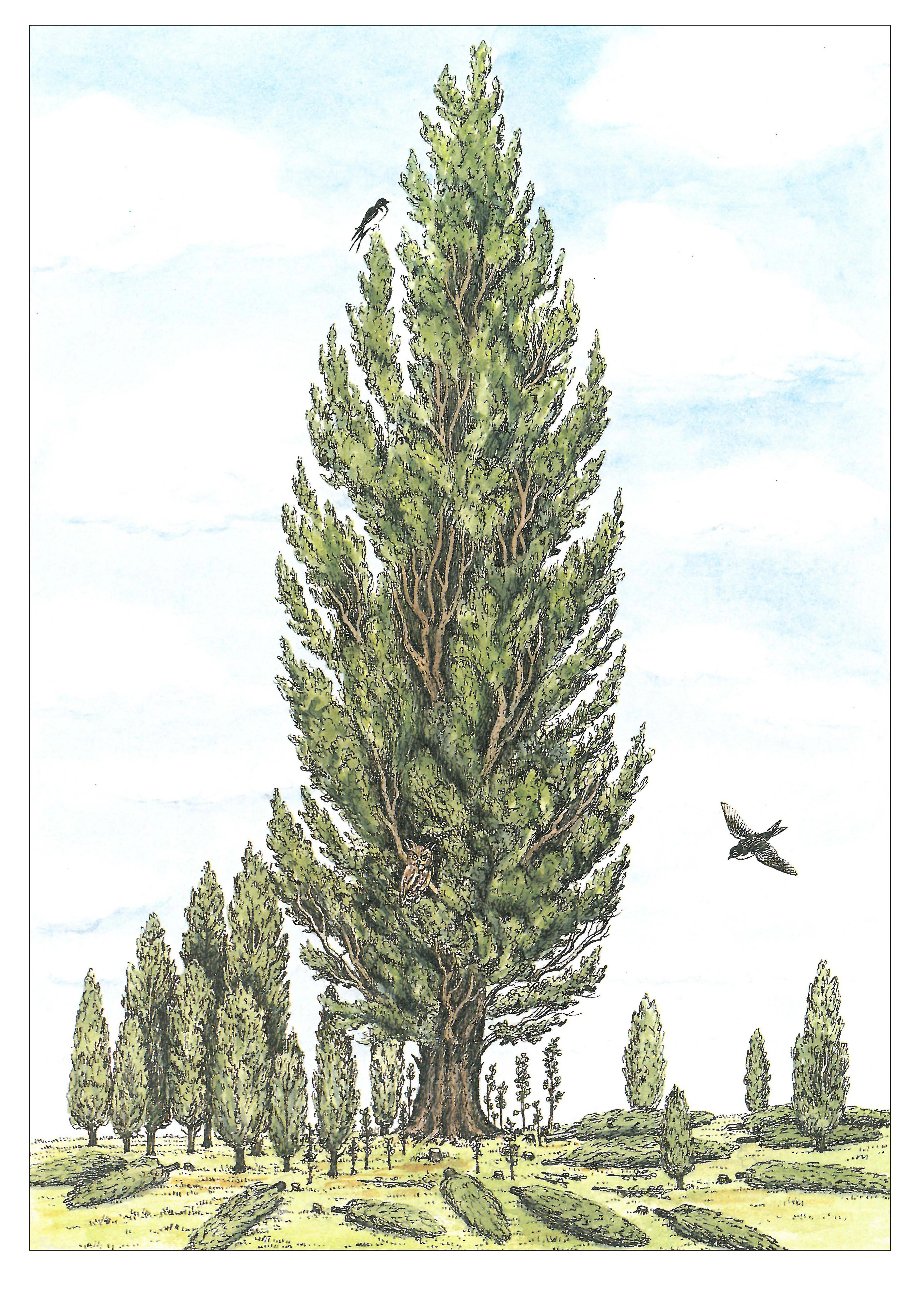

THE OLD POPLAR

For five years our garden was neglected. Then I hired some workers with axes and spades and we went to work in the garden. We cut down and hewed out deadwood and brambles and the odd bush and tree. The poplar and bird-cherry were the worst culprits in being overgrown and stunting other trees. The poplar comes up from the roots, so you simply cannot cut it down, you have to grub out the roots.

Beyond the lake stood a huge poplar, two armfuls in girth. Around it was a glade all overgrown with poplar shoots. I gave the order to cut them down. I wanted the place to be lighter, neater, and most of all, I wanted to make life easier for the old poplar, for I thought all those young trees were coming from it and drawing the sap out of it.

As we were cutting down those young saplings, now and again I had a pang of conscience as we dug out their sap-rich roots. It took four of us to pull up one half-hewn sapling; It was hanging on to its life for all it was worth and did not want to die. And I thought to myself, “They evidently need to live if they cling on to life so firmly.”

But we had to cut them down, so I did. Only subsequently, when it was too late, did I realize we should not have destroyed them.

I had thought that the shoots drew sap from the old poplar, but it turned out to be the other way around. Once I had cut them down the old poplar began to die. When leaves began to appear I noticed that half its boughs were bare, and that summer it withered altogether. It had been dying for some time and, knowing its end was near, had transferred life to its shoots.

That is why they grew so quickly. In wanting to make life easier for it I had killed all its children.

HOW MANY GEESE

MAKE SIX?

A poor peasant once went to the squire to ask for food.

1 comment