The director’s viewpoint is therefore especially valuable. Shakespeare’s plasticity is wonderfully revealed when we hear directors of highly successful productions answering the same questions in very different ways. For this play, it is also especially interesting to hear the voice of those who have been inside the part of Shylock: we accordingly also include interviews with two actors who created the role to high acclaim.

FOUR CENTURIES OF THE MERCHANT: AN OVERVIEW

The performance history of The Merchant of Venice has been dominated by the figure of Shylock: no small feat for a character who appears in fewer scenes than almost any other named character and whose role is dwarfed in size by that of Portia. Nevertheless, tradition has it that Richard Burbage, leading player of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, originated the role of Shylock. Quite how the character of the Jewish moneylender was received on stage at the time has been the subject of much debate and controversy. The actor-manager William Poel, in his Elizabethan-practices production of 1898 at St. George’s Hall in London, played the character in the red wig and beard, traditionally associated with Judas Iscariot, on the assumption that Shakespeare merely made use of an available stock type in order that the vice of greed may “be laughed at and defeated, not primarily because he is a Jew, but because he is a curmudgeon.”1

While more recent history makes the idea of the Jew as stock villain uncomfortable for modern audiences, it must be remembered that, at the time of original performance, the Jewish people had been officially excluded from England for three hundred years and would not be readmitted until 1655. The play’s original performances can therefore be seen in a context of folk legend and caricature, as had been recently perpetuated by Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, with its explicitly Machiavellian villain Barabas epitomizing the fashionable type of the cunning Jew. Barabas was one of the great tragedian Edward Alleyn’s leading roles, and may have provided the incentive for Burbage, the other leading actor of the day, to take a more complex spin on the stock Jewish figure. As recently as 2006, New York’s Theater for a New Audience played the two in repertory together, drawing out the links and influences between the plays.

The play includes a part for William Kempe, the company clown, as Lancelet Gobbo (the name interestingly referencing an earlier Kempe role, Launce of The Two Gentlemen of Verona) and, in Portia, his greatest challenge for a boy actor so far. Portia’s role, comprising almost a quarter of the play’s entire text, required tremendous skill and range from the young actor, and laid down the groundwork for the great breeches-clad heroines of the mature comedies, Viola and Rosalind.

The play was played twice at court in February 1605, suggesting a popularity that had kept the play in the company repertory for the best part of a decade, but after this there is no record of the play being performed again in the seventeenth century. The play’s history in the eighteenth century began, as with many of Shakespeare’s works, as an adaptation, George Granville’s The Jew of Venice (1701). While the title ostensibly shifts the focus from Antonio to Shylock, the company’s leading actor, Thomas Betterton, took the role of Bassanio. Shylock, on the other hand, was played by Thomas Doggett, an actor best known for low comedy. The adapted play emphasized moral ideals: Shylock was a simple comic villain, Bassanio a heroic and romantic lover.

It was not until 1741 that Shakespeare’s text was restored by Charles Macklin at Drury Lane. Macklin, like Doggett before him, was best known for his comic roles, but he deliberately set out to create a more serious interpretation of Shylock. John Doran, for example, notes that in the trial scene “Shylock was natural, calmly confident, and so terribly malignant, that when he whetted his knife … a shudder went round the house.”2 This Shylock posed a genuine threat that the earlier comic villains did not, and thus began the process of reimagining The Merchant of Venice as more than a straightforward comedy. Macklin performed Shylock until 1789 and redefined the role—and the play—for subsequent generations. To Alexander Pope is attributed the pithy tribute “This is the Jew that Shakespeare drew.”3

With the notable exception of David Garrick, most of the major actor-managers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries attempted Shylock, with varying degrees of success. In 1814, at the age of twenty-seven, the then-unknown Edmund Kean made his mark at Drury Lane in which he responded to the tradition laid down by Macklin with a new reading of Shylock. Toby Lelyveld tells us “he was willing to see in Shylock what no one but Shakespeare had seen—the tragedy of a man.”4 Heavily influenced by Garrick’s acting style, Kean’s performance took the Romantic preoccupation with individual passion and applied it to Shylock, allowing audiences to experience sympathy and pity for the antagonist, as William Hazlitt noted in the Morning Chronicle: “Our sympathies are much oftener with him than with his enemies.”5

Henry Irving’s production ran for over a thousand performances from 1879 to 1905 in London and America, and its influence is still felt. Irving’s Shylock was a direct descendant of Macklin and Kean’s, consolidating and emphasizing the role as that of a tragic hero. The Spectator noted that “here is a man whom none can despise, who can raise emotions both of pity and of fear, and make us Christians thrill with a retrospective sense of shame.”6 The use of “us Christians” is revealing of audience responses to the play until this point: audiences expected to identify themselves with the Venetian Christians, and in opposition to the Jewish villain. Where Kean had begun to experiment with sympathy for the “other,” Irving forced his audiences to take sides with Shylock and be outraged by his treatment.

Irving’s production was additionally noted for the spectacle of its set, which followed the celebrated example of Charles Kean’s 1858 staging by including a full-sized Venetian bridge and canal along which the masquers floated in a gondola. The historical locations of The Merchant of Venice have long held a deep fascination for directors and designers, and attempts to re-create elements of Venice have recurred throughout the play’s performance history: even the production at Shakespeare’s Globe in 2007 featured a miniature Bridge of Sighs extending into the yard. This fascination with the city reached its apogee in Michael Radford’s 2005 film (see below).

Irving’s Portia was Ellen Terry, the latest in a long line of prestigious Portias including Kitty Clive (1741), Sarah Siddons (1786), and Ellen Tree (1858, opposite her husband, Kean). However, the longstanding focus on Shylock had had the negative impact of restricting the opportunities available to even the better actresses. Act 5 was often cut during the nineteenth century in order to focus on Shylock’s tragedy, along with the scenes featuring Morocco and Aragon, while much of the Bassanio and Portia plot was mercilessly pruned. Irving himself, in order to present the play as unambiguous tragedy, often replaced Act 5 with Iolanthe, a one-act vehicle for Terry which allowed her to finish the evening’s entertainment without distracting from Shylock’s tragedy.

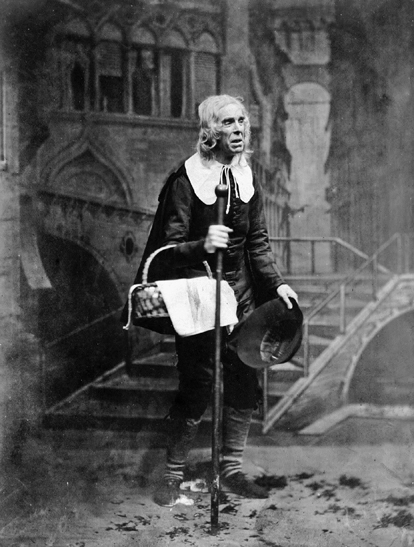

1. Old Gobbo in Charles Kean’s 1858 production, with stage set representing the real Venice.

Despite this, Terry’s Portia set a precedent for imagining the heroine as independent and self-determining. Where Portia had usually been played as entirely subject to the fate dictated by her father, Terry gave reviewers the impression that she would take matters into her own hands if the man she loved failed to choose correctly.

1 comment