$2.87 in 1878, or about £29 (U.S. $45) in today’s purchasing power. Eleven shillings and sixpence would have been barely enough to support Watson in London, where lodgings at a boardinghouse might have cost 7s. per day, although less expensive locations might have run as little as 30s. to 40s. per week. Several scholars suggest that Watson may have been receiving support from his family during this time, although his father and brother had little enough later (see The Sign of Four, text accompanying note 32).

21 Baedeker, in 1896, lists numerous “quiet and comfortable” hotels in the streets leading from the Strand to the Thames. For example, the Arundel Hotel, at No. 19 Arundel St., on the Embankment, charged from 6s. per day for “room, attendance, and breakfast,” with dinner an additional 3s.

22 So named because it originally skirted the bank of the river Thames, the Strand was the great artery of traffic between the City and the West End. It contained many newspaper offices and theatres and has Canonical associations as the home of “Simpson’s” restaurant, a favourite of Holmes (“The Dying Detective” and “The Illustrious Client”), and the namesake of the Strand Magazine, headquartered near the corner of the Strand and Southampton Street, as fancifully depicted on its cover.

23 John Ball expresses the view that Arthur Conan Doyle and Watson met at this time, for both were in similar circumstances, seeking gainful employment as doctors. Whether they met in the offices of a physician’s supplier, at a lecture, or at a library, “a friendship and a collaboration was formed which was to enrich the world. For, great as was the association between Dr. Watson and Sherlock Holmes, of nearly equal importance to posterity was the second collaboration between Dr. Watson and the other physician who was also destined for immortal fame, Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle.”

24 The novelist and Sherlockian scholar Christopher Morley, founder of the Baker Street Irregulars, in an unpublished letter to Edgar Smith, then editor of the Baker Street Journal, proposes January 1, 1881, as the day of Watson’s fateful decision—“a day when Watson would naturally be making resolutions for a more frugal life.” The holiday also explains, suggests Morley, why the laboratory to which Stamford led Watson was all but deserted.

25 The Criterion, more formally the American Bar at the Criterion, near Piccadilly Circus, was an establishment that Michael Harrison deems (in The London of Sherlock Holmes) “one of London’s then more expensive bars.” It was also, according to James E. Holroyd, a gathering place for horse-racing aficionados—thus, a likely haunt for Watson, whom Holmes, in “Shoscombe Old Place,” affectionately referred to as his “Handy Guide to the Turf.” Today the Bar is gone, but the Criterion Brasserie has returned to its former architectural glory, and a plaque at the Brasserie commemorates the meeting of Stamford and Watson.

26 J. N. Williamson, in “The Sad Case of Young Stamford,” argues that “young Stamford” had criminal tendencies known to Holmes, which explains why Stamford declined the opportunity to room with Holmes. Young Stamford is the same person, according to Williamson, as Archie Stamford, the forger mentioned in passing in “The Solitary Cyclist.” This same young man, in Williamson’s theory, pops up again as “Archie,” an associate of the villainous John Clay in “The Red-Headed League.” Williamson posits that he was captured and apparently turned to lawful means of employment; Holmes sends to “Stamford” in the Strand text of The Hound of the Baskervilles to obtain an Ordnance map (although the latter is demonstrably a slip of the pen for “Stanford’s,” the well-known map establishment). Taking an altogether different tack is H.E.B. Curjel, who, in “Young Doctor Stamford of Barts,” postulates that Stamford is a member of the teaching staff in the anatomy department of Barts—whereas Cal Wood, in “Stamford: A Closer Look,” takes the somewhat far-fetched view that Stamford was Holmes’s roommate.

27 A surgeon’s assistant.

28 St. Bartholomew’s Hospital Medical College, known popularly as “Barts” or “Bart’s,” was founded in 1123 by—legend has it—Rahere, a jester at Henry I’s court. Having taken ill in Rome, Rahere prayed on the banks of the Tiber, on the island of St. Bartholomew, that he might recover in time to die on his native soil. St. Bartholomew appeared to him in a vision, commanding him to return to London and build a church and hospital in his name. By 1896, the hospital had grown to 678 beds, treating some 6,500 in-patients and 16,000 out-patients annually. Among the instructors at its famous medical school (which was opened in 1843) was William Harvey (1578–1657), who both determined the role of the heart in the circulation of blood and demonstrated how blood flowed in a continuous cycle.

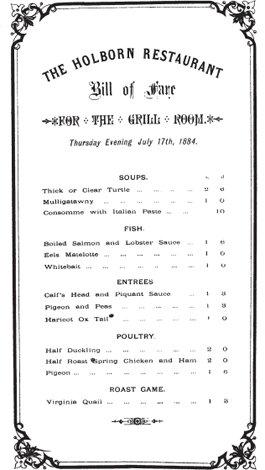

29 An 1880 advertisement for the Holborn Restaurant described it as “one of the sights and one of the comforts of London,” combining the “attractions of the chief Parisian establishments with the quiet and order essential to English custom.” William H. Gill, in “Some Notable Sherlockian Buildings,” takes a less benign view, describing the restaurant architecturally as “Victorian classicism at its worst.”

The Holborn was known as a favoured establishment of the Prince of Wales, which may well have impressed the young Watson and Stamford. Lieut. Col. Newnham-Davis captured something of the Holborn’s scale in his Dinners and Diners: Where and How to Dine in London (1899), in which he and his dining companion “wanted something a little more elaborate than a grill-room would give us, and more amusing company than we were likely to find at the smaller dining places we knew of.” During dinner in “the many-coloured marble hall, with its marble staircase springing from either side,” Newnham-Davis and his companion listen to “a good band, but much too loud” and dine on beef and brussels sprouts, chicken and ham; when they refuse dessert, the waiter expresses concern “that something must be the matter with us, for most people at the Holborn eat their dinner steadily through.” Chapter 16 of the same book recounts Newnham-Davis’s dining experience at the American Bar at the Criterion, a “very good place for an undress dinner.”

Holborn Restaurant (ca. 1900).

Menu from the Holborn Restaurant, 1884.

30 Ian McQueen expresses doubt that Watson’s tan, if in fact acquired, would have survived his journey from Afghanistan to London.

1 comment