That was where the man had rested the lapstone—a peculiarity only found in cobblers.

All this impressed me very much. He was continually before me—his sharp, piercing eyes, eagle nose, and striking features. There he would sit in in his chair with fingers together—he was very dextrous with his hands—and just look at the man or woman before him. He was most kind and painstaking with the students—a real good friend—and when I took my degree and went to Africa the remarkable individuality and discriminating tact of my old master made a deep and lasting impression on me, though I had not the faintest idea that it would one day lead me to forsake medicine for story-writing.

“That it did lead Dr. Doyle ‘to forsake medicine for story-writing,’ and with what result, every one knows. And as Mr. Sherlock Holmes has now become a household word and almost a public institution, the publishers of ‘A Study in Scarlet’ hope that the following paper, in which some particulars of Dr. Doyle’s early education and training, and of the circumstances which led him to form the habit of making careful observations, will prove of interest to his many readers. Their cordial thanks are due to Dr. Doyle, Dr. Bell, and to the editor and proprietors of The Bookman for courteously consenting to the reproduction of the paper.” (Dr. Bell’s paper is reproduced as an Appendix to this tale.)

A Study in Scarlet.

(London: Ward Lock & Co., 1888)

PART

I

I

(Being a reprint from the reminiscences of John H.2 Watson, M.D., late of the Army Medical Department3)4

CHAPTER

I

MR. SHERLOCK HOLMES

IN THE YEAR 1878 I took my degree of Doctor of Medicine5 of the University of London,6 and proceeded to Netley7 to go through the course prescribed for surgeons in the Army.8 Having completed my studies there, I was duly attached to the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers9 as Assistant Surgeon. The regiment was stationed in India at the time, and before I could join it, the second Afghan war10 had broken out. On landing at Bombay, I learned that my corps had advanced through the passes, and was already deep in the enemy’s country. I followed, however, with many other officers who were in the same situation as myself, and succeeded in reaching Candahar11 in safety, where I found my regiment, and at once entered upon my new duties.

The campaign brought honours and promotion to many, but for me it had nothing but misfortune and disaster. I was removed from my brigade and attached to the Berkshires,12 with whom I served at the fatal battle of Maiwand.13 There I was struck on the shoulder14 by a Jezail15 bullet, which shattered the bone and grazed the subclavian artery. I should have fallen into the hands of the murderous Ghazis16 had it not been for the devotion and courage shown by Murray,17 my orderly, who threw me across a pack-horse, and succeeded in bringing me safely to the British lines.

Worn with pain, and weak from the prolonged hardships which I had undergone, I was removed, with a great train of wounded sufferers, to the base hospital at Peshawur. Here I rallied, and had already improved so far as to be able to walk about the wards, and even to bask a little upon the verandah, when I was struck down by enteric fever,18 that curse of our Indian possessions. For months my life was despaired of, and when at last I came to myself and became convalescent, I was so weak and emaciated that a medical board determined that not a day should be lost in sending me back to England. I was despatched, accordingly, in the troopship Orontes, and landed a month later on Portsmouth jetty, with my health irretrievably ruined, but with permission from a paternal government to spend the next nine months in attempting to improve it.

“I should have fallen into the hands of the murderous ghazis had it not been for the devotion and courage shown by Murray, my orderly.”

Richard Gutschmidt, Späte Rache (Stuttgart: Robert Lutz Verlag, 1902)

I had neither kith nor kin in England,19 and was therefore as free as air—or as free as an income of eleven shillings and sixpence20 a day will permit a man to be. Under such circumstances, I naturally gravitated to London, that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained. There I stayed for some time at a private hotel21 in the Strand,22 leading a comfortless, meaningless existence, and spending such money as I had, considerably more freely than I ought. So alarming did the state of my finances become, that I soon realized that I must either leave the metropolis and rusticate somewhere in the country, or that I must make a complete alteration in my style of living.23 Choosing the latter alternative, I began by making up my mind to leave the hotel, and to take up my quarters in some less pretentious and less expensive domicile.

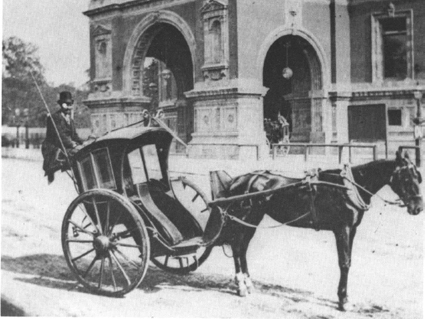

On the very day that I had come to this conclusion,24 I was standing at the Criterion Bar,25 when someone tapped me on the shoulder, and turning round I recognized young Stamford,26 who had been a dresser27 under me at Bart’s.28 The sight of a friendly face in the great wilderness of London is a pleasant thing indeed to a lonely man. In old days Stamford had never been a particular crony of mine, but now I hailed him with enthusiasm, and he, in his turn, appeared to be delighted to see me. In the exuberance of my joy, I asked him to lunch with me at the Holborn,29 and we started off together in a hansom.

Criterion Bar, interior (ca. 1881).

A hansom cab outside the Albert Hall (1900).

Victorian and Edwardian London

“Whatever have you been doing with yourself, Watson?” he asked in undisguised wonder, as we rattled through the crowded London streets. “You are as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut.”30

I gave him a short sketch of my adventures, and had hardly concluded it by the time that we reached our destination.

“Poor devil!” he said, commiseratingly, after he had listened to my misfortunes. “What are you up to now?”

“Looking for lodgings,” I answered. “Trying to solve the problem as to whether it is possible to get comfortable rooms at a reasonable price.”

“That’s a strange thing,” remarked my companion; “you are the second man to-day that has used that expression to me.”

“And who was the first?” I asked.

“A fellow who is working at the chemical laboratory up at the hospital. He was bemoaning himself this morning because he could not get someone to go halves with him in some nice rooms which he had found, and which were too much for his purse.”

“By Jove!” I cried, “if he really wants someone to share the rooms and the expense, I am the very man for him. I should prefer having a partner to being alone.”

Young Stamford looked rather strangely at me over his wine-glass.31 “You don’t know Sherlock Holmes yet,” he said; “perhaps you would not care for him as a constant companion.”

“Why, what is there against him?”

“Oh, I didn’t say there was anything against him.

1 comment