The sickness continued with unabated violence for more than an hour after the stomach had been evidently completely emptied, and was accompanied with other internal derangement and severe cramps both in the stomach and the extremities. I at once sent to my house for a portable bath I happened to have hired for my own wife’s use, and on its arrival, placed Mrs. Anderton in it at a temperature of 98°, having previously added three quarters of a pound of mustard. While waiting for the bath, I administered thirty drops of laudanum in a wine-glassful of hot brandy-and-water, but without, in any degree, checking the symptoms before mentioned, which continued almost incessantly. They were accompanied also by violent pains and great swelling of the “epigastrium.” A fresh dose of opium was equally unsuccessful, nor was any amelioration of symptoms produced by the exhibition of prussic acid and creosote. On removing the patient from the warm bath, I had her carefully placed in bed, shortly after which she began to perspire profusely, but without any relief to the other symptoms.

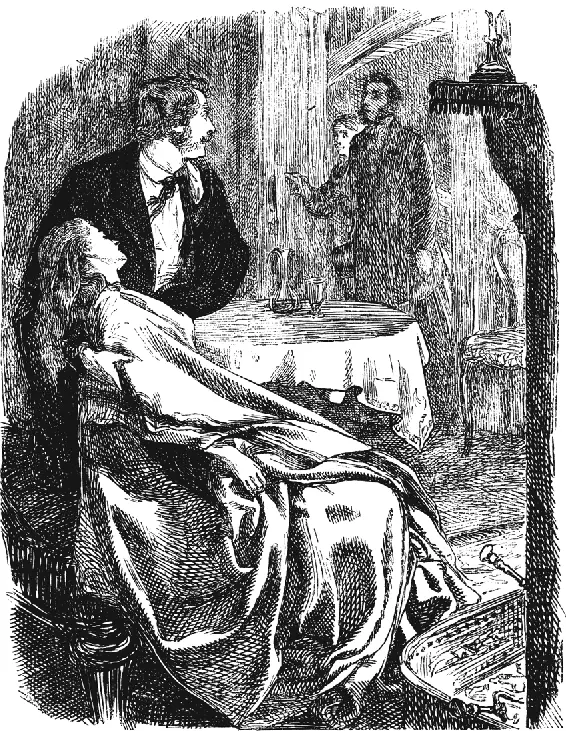

‘On arriving at the house I found Mr. Anderton supporting his wife in his arms…Mrs. Anderton was on the couch in her dressing-room, partially undressed, but with two or three blankets thrown over her, as she seemed shivering with the cold.’

[The narrative here recommences.]

‘I now began to fear that some deleterious substance had been swallowed, more especially as the patient had, up to the very moment of her seizure, been in unusually good health. I therefore made careful examinations with the view to detecting the presence of arsenic; and instituted, by the aid of Mr. Anderton, the strictest enquiries as to whether there was in the house any preparation containing this or any other irritant poison. Nothing of the kind could, however, be found, nor were such tests, as I was at the time in a position to apply, able to detect anything of the kind to which my suspicions were directed. Deliberate poisoning proved, moreover, on consideration, entirely out of the question, as there could be no doubt of Mr. Anderton’s devoted attachment to his wife, and the people of the house were entire strangers to her. Moreover, the length of time since any food had been taken was almost conclusive against such a supposition. Mrs. Anderton had dined at six o’clock, and between that hour and midnight, when the attack came on, had eaten nothing but a biscuit and part of a glass of sherry-and-water, the remainder of which was in the glass upon the dressing-room table when I arrived. Since then I have removed portions of all the matters tested, as well as the remaining wine-and-water, and have had them thoroughly examined by a scientific chemist, but equally without result. I am compelled, therefore, to believe that the symptoms arose from some natural, though undiscovered cause. Possibly from a sudden chill in coming from the heated rooms into the night air, though this seems hardly compatible with the fact that she never complained of cold during the long drive home, and that she was seated comfortably in her dressing-room, making her customary entries in her journal, when the attack came on. Another very suspicious circumstance was that, afterwards mentioned by her, of a strong metallic taste in the mouth, a symptom sometimes occasioned, and in conjunction likewise with the others noticed in her case, by the exhibition of excessive doses of antimony in the form of emetic tartar. This medicine, however, had never been prescribed for her, nor was there any possibility of her having had access to any in mistake. At Mr. Anderton’s request, however, I exhibited the remedies used in such a case, as port wine, infusion of oakbark, &c., but with as little effect as the other medicines. Indeed, the remedies of whatever kind were precluded from exercising their full action by the extreme irritability of the stomach, by which they were rejected almost as soon as swallowed. This being the case, I abandoned any further attempt at the exhibition of the heavy doses I had hitherto employed, or indeed of drugs of any kind, and confined myself, until the irritation of the “epigastrium” should have been in some measure allayed, to a treatment I have occasionally found successful in somewhat similar cases; the administration, that is to say, of simple soda-water in repeated doses of a teaspoonful at a time. I have often found this to remain with good effect upon the stomach when everything else was at once rejected, nor was I disappointed in the present case. About an hour after commencing this treatment, the first violence of the symptoms began to subside, and by the next afternoon the case had resolved itself into an ordinary one of severe “gastro-enteritis,” which I then proceeded to treat in the regular manner. After quite as short a period as I could possibly have expected, this also was subdued, leaving the patient, however, in a state of great prostration, and subject to night-perspirations of the most lowering character. I now began to throw in tonics, and to resort, though very cautiously, to more invigorating diet. Under this treatment she continued steadily to improve, though the perspirations still continued, and her constitution cannot be said to have at all recovered the severe shock it had sustained by the month of April 1855, when they left Dover, by my recommendation, for change of air.

1 comment