All the recorded history of England is full of that group of harbours and that little inland sea, and before history began, to strike the island here was to be nearest to Salisbury Plain and to find the cross-roads of all the British communications close at hand; the tracks to the east, to the west, to the Midlands were all equally accessible.

Finally, it must be noted that the deepest invasion of the land made here is made by the submerged valley of Southampton Water, and the continuation of that valley inward is the valley of the Itchen. The inland town to which the port corresponded (just as we found Canterbury corresponding to the Kentish harbours) is Winchester.

Thus it was that Winchester grew to be the most important place in south England. How early we do not know, but certainly deeper than even tradition or popular song can go it gathered round itself the first functions of leadership. It was possessed of a sanctity which it has not wholly lost. It preserves, from its very decay, a full suggestion of its limitless age. Its trees, its plan, and the accent of the spoken language in its streets are old. It maintains the irregularities and accretions in building which are, as it were, the outer shell of antiquity in a city. Its parallels in Europe can hardly show so complete a conservation. Rheims is a great and wealthy town. The Gaulish shrine of 'the Virgin that should bear a Son' still supports from beneath the ground the high altar of Chartres. The sacred well of a forgotten heathendom still supports with its roof the choir of Winchester.[1] But Chartres is alive, the same woman is still worshipped there; the memory of Winchester is held close in a rigidity of frost which keeps intact the very details of the time in which it died. It was yielding to London before the twelfth century closed, and it is still half barbaric, still Norman in its general note. The spires of the true Middle Ages never rose in it. The ogive, though it is present, does not illumine the long low weight of the great church. It is as though the light of the thirteenth century had never shone upon or relieved it.

It belongs to the snow, to winter, and to the bare trees of the cold wherein the rooks still cry 'Cras! cras!' to whatever lingers in the town. So I saw it when I was to begin the journey of which I write in these pages.

To return to the origins. The site of Winchester, I say, before ever our legends arose, had all the characters which kept it vigorous to within seven hundred years of our own time. It was central, it held the key to the only good middle passage the Channel afforded, it was destined to be a capital. From Winchester therefore a road must necessarily have set out to join what had been, even before the rise of Winchester, the old eastern and western road; this old road it would join by a slow approach, and merge with it at last and seek Canterbury as a goal.

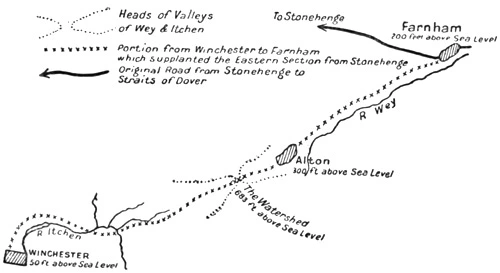

The way by which men leaving Winchester would have made for the Straits may have been, at first, a direct path leading northwards towards the point where the old east-and-west road came nearest to that city. For in the transformation of communication it is always so: we see it in our modern railway lines, and in the lanes that lead from new houses to the highways: the first effort is to find the established road, the 'guide,' as soon as possible.

Later attempts were made at a short cut. Perhaps the second attempt was to go somewhat eastward, towards what the Romans called Calleva, and the Roman road from Winchester to Calleva (or Silchester) may have taken for its basis some such British track. But at any rate, the gradual experience of travel ended in the shortest cut that could be found. The tributary road from Winchester went at last well to the east, and did not join the original track till it reached Farnham.

This short cut, feeder, or tributary which ultimately formed the western end of our Road was driven into a channel which attracted it to Farnham almost as clearly as the chalk hills of which I have spoken pointed out the remainder of the way: for two river valleys, that of the Itchen and that of the Wey led straight to that town and to the beginning of the hill-platform.

GLIMPSES OF THE ITCHEN AWAY BEHIND US

See page 133

It is the universal method of communication between neighbouring centres on either side of a watershed to follow, if they exist, two streams; one leading up to and the other down from the watershed. This method provides food and drink upon the way, it reduces all climbing to the one clamber over the saddle of the ridge, and, if the beginning of the path is struck out by doubtful pioneers, then, as every pioneer in a new country knows, ascending a stream is the best guide to a pass and descending one on the further side is the best guide to open spaces, and to the habitations of men.

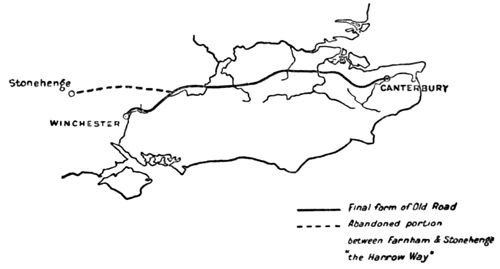

This tributary gradually superseded the western end of the trail, and the Old Road from the west to the east, from the metal mines to the Straits of Dover, had at last Winchester for an origin and Canterbury for a goal. The neglected western end from Farnham to Stonehenge became called 'The Harrow Way,' that is the 'Hoar,' the 'Ancient' way.[2] It fell into disuse, and is now hardly to be recognised at all.

The prehistoric road as we know it went then at last in a great flat curve from Winchester to Canterbury, following the simplest opportunities nature afforded. It went eastward, first up the vale of the Itchen to the watershed, then down the vale of the Wey, and shortly after Farnham struck the range of the North Downs, to which it continued to cling as far as the valley of the Stour, where a short addition led it on to Canterbury.

Its general direction, therefore, when it had settled down into its final form, was something of this sort:—

When Winchester began to affirm itself as the necessary centre of south England—that is of open, rich, populated, and cultivated England—the new tributary road would rapidly grow in importance; and finally, the main traffic from the western hills and from much of the sea also, from Spain, from Brittany, and from western Normandy, probably from all southern Ireland, from the Mendips, the south of Wales, and the Cornish peninsula, would be canalised through Winchester. The road from Winchester to Farnham and so to Canterbury would take an increasing traffic, would become the main artery between the west and the Straits of Dover, and would leave the most permanent memorials of its service.

Winchester and Canterbury being thus each formed by the sea, and each by similar conditions in the action of that sea, the parallel between them can be drawn to a considerable length, and will prove of the greatest value when we come to examine the attitude of the Old Road towards the two cities which it connects. The feature that puzzles us in the approach to Canterbury may be explained by a reference to Winchester. An unsolved problem at the Winchester end may be referred for its solution to Canterbury, and the evidence of the two combined will be sufficient to convince us that the characters they possess in common are due to much more than accident.

Of all the sites which might have achieved some special position after the official machinery of Rome with its arbitrary power of choice had disappeared, these two rose pre-eminent at the very entry to the Dark Ages, and retained that dual pre-eminence until the great transition into the light, the Renaissance of civilisation at the end of the twelfth century and the beginning of the thirteenth.

For six or seven hundred years the two towns were the peculiar centres of English life.

1 comment