The ›rules‹ are grounded in ›authority‹; and this ›authority‹ – can any one tell us what it means? or can any one suggest any thing that it may not mean? Is it not clear that the ›scholar‹ above referred to, might as readily have deduced from authority a totally false system as a partially true one? To deduce from authority a consistent prosody of the ancient metres would indeed have been within the limits of the barest possibility; and the task has not been accomplished, for the reason that it demands a species of ratiocination altogether out of keeping with the brain of a bookworm. A rigid scrutiny will show that the very few ›rules‹ which have not as many exceptions as examples, are those which have, by accident, their true bases not in authority, but in the omniprevalent laws of syllabification; such, for example, as the rule which declares a vowel before two consonants to be long.

In a word, the gross confusion and antagonism of the scholastic prosody, as well as its marked inapplicability to the reading flow of the rhythms it pretends to illustrate, are attributable, first, to the utter absence of natural principle as a guide in the investigations which have been undertaken by inadequate men; and secondly, to the neglect of the obvious consideration that the ancient poems, which have been the criteria throughout, were the work of men who must have written as loosely, and with as little definitive system, as ourselves.

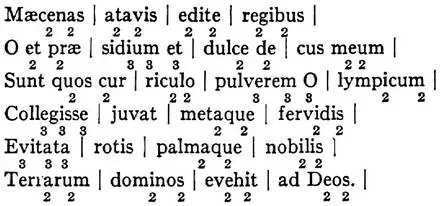

Were Horace alive to-day, he would divide for us his first Ode thus, and ›make great eyes‹ when assured by prosodists that he had no business to make any such division!

Read by this scansion, the flow is preserved; and the more we dwell on the divisions, the more the intended rhythm becomes apparent. Moreover, the feet have all the same time; while, in the scholastic scansion, trochees – admitted trochees – are absurdly employed as equivalents to spondees and dactyls. The books declare, for instance, that Colle, which begins the fourth line, is a trochee, and seem to be gloriously unconscious that to put a trochee in opposition with a longer foot, is to violate the inviolable principle of all music, time.

It will be said, however, by ›some people,‹ that I have no business to make a dactyl out of such obviously long syllables as sunt, quos, cur. Certainly I have no business to do so. I never do so. And Horace should not have done so. But he did. Mr. Bryant and Mr. Longfellow do the same thing every day. And merely because these gentlemen, now and then, forget themselves in this way, it would be hard if some future prosodist should insist upon twisting the »Thanatopsis,« or the »Spanish Student,« into a jumble of trochees, spondees, and dactyls.

It may be said, also, by some other people, that in the word decus, I have succeeded no better than the books, in making the scansional agree with the reading flow; and that decus was not pronounced decus. I reply, that there can be no doubt of the word having been pronounced, in this case, decus. It must be observed, that the Latin inflection, or variation of a word in its terminating syllable, caused the Romans – must have caused them – to pay greater attention to the termination of a word than to its commencement, or than we do to the terminations of our words. The end of the Latin word established that relation of the word with other words which we establish by prepositions or auxiliary verbs. Therefore, it would seem infinitely less odd to them than it does to us, to dwell at any time, for any slight purpose, abnormally, on a terminating syllable. In verse, this license – scarcely a license – would be frequently admitted. These ideas unlock the secret of such lines as the

Litoreis ingens inventa sub ilicibus sus,

and the

Parturiunt montes et nascitur ridiculus mus,

which I quoted, some time ago, while speaking of rhyme.

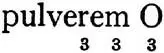

As regards the prosodial elisions, such as that of rem before O, in pulverem Olympicum, it is really difficult to understand how so dismally silly a notion could have entered the brain even of a pedant. Were it demanded of me why the books cut off one vowel before another, I might say: It is, perhaps, because the books think that, since a bad reader is so apt to slide the one vowel into the other at any rate, it is just as well to print them ready-slided. But in the case of the terminating m, which is the most readily pronounced of all consonants (as the infantile mamma will testify), and the most impossible to cheat the ear of by any system of sliding – in the case of the m, I should be driven to reply that, to the best of my belief, the prosodists did the thing, because they had a fancy for doing it, and wished to see how funny it would look after it was done. The thinking reader will perceive that, from the great facility with which em may be enunciated, it is admirably suited to form one of the rapid short syllables in the bastard dactyl ( ); but because the books had no conception of a bastard dactyl, they knocked it on the head at once – by cutting off its tail!

); but because the books had no conception of a bastard dactyl, they knocked it on the head at once – by cutting off its tail!

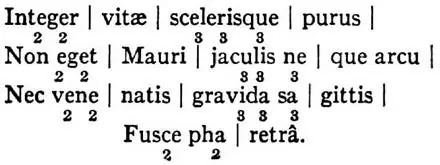

Let me now give a specimen of the true scansion of another Horatian measure – embodying an instance of proper elision.

Here the regular recurrence of the bastard dactyl gives great animation to the rhythm. The e before the a in que arcu, is, almost of sheer necessity, cut off – that is to say, run into the a so as to preserve the spondee. But even this license it would have been better not to take.

Had I space, nothing would afford me greater pleasure than to proceed with the scansion of all the ancient rhythms, and to show how easily, by the help of common-sense, the intended music of each and all can be rendered instantaneously apparent. But I have already overstepped my limits, and must bring this paper to an end.

It will never do, however, to omit all mention of the heroic hexameter.

I began the ›processes‹ by a suggestion of the spondee as the first step toward verse. But the innate monotony of the spondee has caused its disappearance, as the basis of rhythm, from all modern poetry. We may say, indeed, that the French heroic – the most wretchedly monotonous verse in existence – is, to all intents and purposes, spondaic. But it is not designedly spondaic – and if the French were ever to examine it at all, they would no doubt pronounce it iambic. It must be observed that the French language is strangely peculiar in this point – that it is without accentuation, and consequently without verse. The genius of the people, rather than the structure of the tongue, declares that their words are, for the most part, enunciated with a uniform dwelling on each syllable. For example, we say »syllabfication.« A Frenchman would say syl-la-bi-fi-ca-ti-on; dwelling on no one of the syllables with any noticeable particularity.

1 comment