The Riddle of the Sands

Contents

Preface to the original edition

List of Illustrations

Case Notes

Preface to the original edition

A WORD about the origin and authorship of this book.

In October last (1902), my friend ‘Carruthers’ visited me in my chambers, and, under a provisional pledge of secrecy, told me frankly the whole of the adventure described in these pages. Till then I had only known as much as the rest of his friends, namely, that he had recently undergone experiences during a yachting cruise with a certain Mr ‘Davies’ which had left a deep mark on his character and habits.

At the end of his narrative – which, from its bearing on studies and speculations of my own, as well as from its intrinsic interest and racy delivery, made a very deep impression on me – he added that the important facts discovered in the course of the cruise had without a moment’s delay been communicated to the proper authorities, who, after some dignified incredulity, due in part, perhaps, to the pitiful inadequacy of their own secret service, had, he believed, made use of them, to avert a great national danger. I say ‘he believed,’ for though it was beyond question that the danger was averted for the time, it was doubtful whether they had stirred a foot to combat it, the secret discovered being of such a nature that mere suspicion of it on this side was likely to destroy its efficacy.

There, however that may be, the matter rested for a while, as, for personal reasons which will be manifest to the reader, he and Mr ‘Davies’ expressly wished it to rest.

But political tendencies were driving them to reconsider their decision. These showed with disastrous plainness that the information wrung with such peril and labour from the German Government and transmitted so promptly to our own had

had none but the most transitory effect, if any, on our policy. On the contrary, some poisonous influence, whose origin still baffles all but a very few, was persistently at work to drive back our diplomacy into paths which even without this clarion warning they would be wise on principle to shun. As a drastic cure for what had come to be nothing less than a national disease, the two friends now had a mind to make their story public; and it was about this that ‘Carruthers’ wished for my advice. The great drawback was that an Englishman, bearing an honoured name, was disgracefully implicated, and that unless infinite delicacy were used, innocent persons, and, especially, a young lady, would suffer pain and indignity, if his identity were known. Indeed troublesome rumours, containing a grain of truth and a mass of falsehood, were already afloat.

After weighing both sides of the question, I gave my vote emphatically for publication. The personal drawbacks could, I thought, with tact be neutralized; while, from the public point of view, the case was just one of those which unhappily occur with increasing frequency nowadays, when matters that properly should be confined to the seclusion of the statesman’s study must perforce be removed from it and submitted to the common sense of the country at large: a common sense which all thoughtful observers know to be growing, while statesmanship is declining. Conspicuous proofs of this, the most striking feature in the growth of modern democracy, abound in our recent history.

Publication was agreed upon, and the next point was the form it should take. ‘Carruthers,’ with the concurrence of Mr ‘Davies,’ was for a bald exposition of the essential facts, stripped of their warm human envelope. I was strongly against this course, firstly, because it would aggravate instead of allaying the rumours that were current; secondly, because in such a form the narrative would not carry conviction, and would thus defeat its own end. The persons and the events are indissolubly connected; to evade, abridge, suppress,

would be to convey to the reader the idea of a concocted hoax. Indeed, I took bolder ground still, urging that the story should be made as explicit and circumstantial as possible, frankly and honestly for the purpose of entertaining and so attracting a wide circle of readers. Even anonymity was undesirable. Nevertheless certain precautions were imperatively needed.

To cut the matter short, they asked for my assistance and received it at once. It was arranged that I should edit the book; that ‘Carruthers’ should give me his diary and recount to me in fuller detail and from his own point of view all the phases of the ‘quest,’ as they used to call it; that Mr ‘Davies’ should meet me with his charts and maps and do the same, and that the whole story should be written, as from the mouth of the former, with its humours and errors, its light and its dark side, just as it happened; with the following few limitations. The year it belongs to is disguised; the names of persons are throughout fictitious, and at my instance certain slight liberties have been taken to conceal the identity of the English characters.

Remember, also, that these persons are living now in the midst of us, and if you find one topic touched on with a light and hesitating pen, do not blame the Editor, who, whether they are known or not, would rather say too little than say a word that might savour of impertinence.

E. C.

March 1903

List of Illustrations

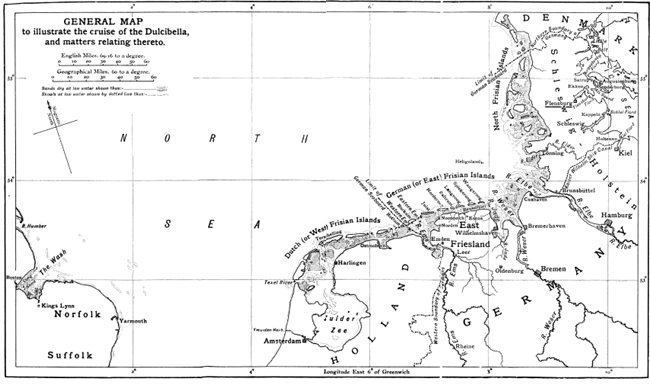

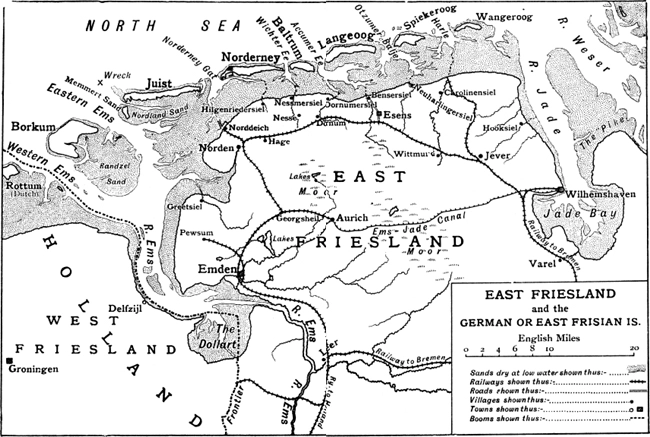

Map A

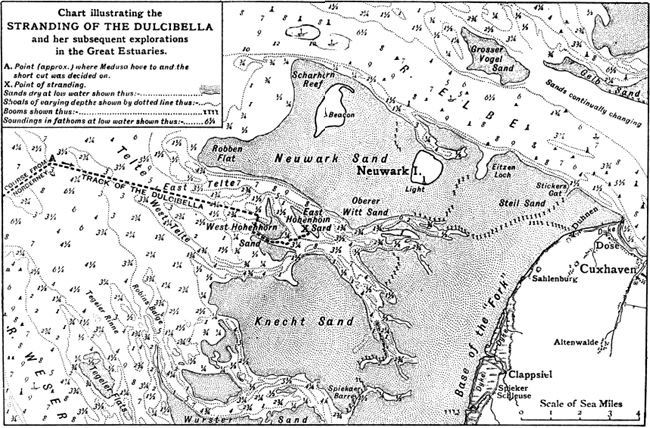

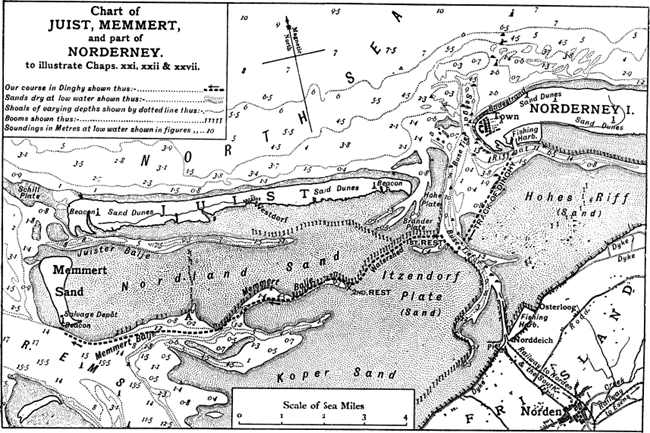

Chart A

Map B

Chart B

The charts shown on pages xiv-xv and xviii-xix are reproductions, on a slightly reduced scale, and omitting some confusing and irrelevant details, of British and German Admiralty Charts.

Chapter 1

The Letter

I HAVE read of men who, when forced by their calling to live for long periods in utter solitude – save for a few black faces – have made it a rule to dress regularly for dinner in order to maintain their self-respect and prevent a relapse into barbarism. It was in some such spirit, with an added touch of self-consciousness, that, at seven o’clock in the evening of September 23 in a recent year, I was making my evening toilet in my chambers in Pall Mall. I thought the date and the place justified the parallel: to my advantage even; for the obscure Burmese administrator might well be a man of blunted sensibilities and coarse fibre, and at least he is alone with nature, while I – well, a young man of condition and fashion, who knows the right people, belongs to the right clubs, has a safe, possibly a brilliant future in the Foreign Office, may be excused for a sense of complacent martyrdom, when, with his keen appreciation of the social calendar, he is doomed to the outer solitude of London in September. I say ‘martyrdom,’ but in fact the case was infinitely worse. For to feel oneself a martyr, as everybody knows, is a pleasurable thing, and the true tragedy of my position was that I had passed that stage. I had enjoyed what sweets it had to offer in ever dwindling degree since the middle of August, when ties were still fresh and sympathy abundant. I had been conscious that I was missed at Morven Lodge party. Lady Ashleigh herself had said so in the kindest possible manner, when she wrote to acknowledge the letter in which I explained, with an effectively

austere reserve of language, that circumstances compelled me to remain at my office. ‘We know how busy you must be just now,’ she wrote, ‘and I do hope you won’t overwork: we shall all miss you very much.’ Friend after friend ‘got away’ to sport and fresh air with promises to write and chaffing condolences, and, as each deserted the sinking ship, I took a grim delight in my misery, positively almost enjoying the first week or two after my world had been finally dissipated to the four bracing winds of heaven. I began to take a spurious interest in the remaining five millions, and wrote several clever letters in a vein of cheap satire, indirectly suggesting the pathos of my position, but indicating that I was broadminded enough to find intellectual entertainment in the scenes, persons, and habits of London in the dead season. I even did rational things at the instigation of others. For, though I should have liked total isolation best, I of course found that there was a sediment of unfortunates like myself who, unlike me, viewed the situation in a most prosaic light.

1 comment