M. Young, Byron’s first mentor, in a long,

thoughtful review in the Sunday Times, placed Byron in the tradition of his

namesake: “the last and finest fruit of the insolent

humanism of the eighteenth century.”

But by now all humanism was under threat, and Byron had flung himself into

a clamorous crusade against Fascism. The outbreak of war found him employed in

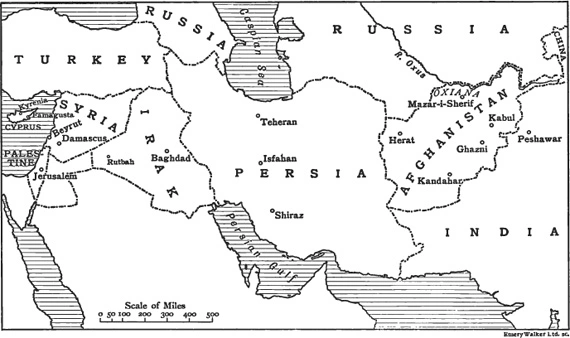

propaganda by the BBC, and in February 1941, under cover of journalism, he set sail for

Alexandria on an espionage mission to observe Russian activity in northeast Iran. He was

thirty-five. Three days out to sea, somewhere beyond Scotland’s Cape Wrath,

his boat was torpedoed and sunk, and Byron presumed drowned, leaving behind bitter

speculation on all that he might have done.

Colin Thubron

ENTRIES

PART I

Venice

s.s. “Italia”

CYPRUS

Kyrenia

Nicosia

Famagusta

Larnaca

s.s. “Martha Washington”

PALESTINE

Jerusalem

SYRIA

Damascus

Beyrut

Damascus

IRAK

Baghdad

PART II

PERSIA

Kirmanshah

Teheran

Gulhek

Teheran

Zinjan

Tabriz

Maragha

Tasr Kand

Saoma

Kala Julk

Ak Bulagh

Zinjan

PART III

Teheran

Ayn Varzan

Shahrud

Nishapur

Meshed

AFGHANISTAN

Herat

Karokh

Kala Nao

Laman

Karokh

Herat

PERSIA

Meshed

Teheran

PART IV

Teheran

Kum

Delijan

Isfahan

Abadeh

Shiraz

Kavar

Firuzabad

Ibrahimabad

Shiraz

Kazerun

Persepolis

Abadeh

Isfahan

Yezd

Bahramabad

Kirman

Mahun

Yezd

Isfahan

Teheran

Sultaniya

Teheran

PART V

Shahi

Asterabad

Gumbad-i-Kabus

Bandar shah

Samnan

Damghan

Abbasabad

Meshed

Kariz

AFGHANISTAN

Herat

Moghor

Bala Murghab

Maimena

Andkhoi

Mazar-i-Sherif

Kunduz

Khanabad

Bamian

Shibar

Charikar

Kabul

INDIA

Peshawar

The Frontier Mail

s.s. “Maloja”

ENGLAND

Savernake

PART I

PART I

Venice, August 20th, 1933.—Here as a joy-hog: a pleasant change after that pension on the Giudecca two years ago. We went to the Lido this morning, and the Doge’s Palace looked more beautiful from a speed-boat than it ever did from a gondola. The bathing, on a calm day, must be the worst in Europe: water like hot saliva, cigar-ends floating into one’s mouth, and shoals of jelly-fish.

Lifar came to dinner. Bertie mentioned that all whales have syphilis.

Venice, August 21st.—After inspecting two palaces, the Labiena, containing Tiepolo’s fresco of Cleopatra’s Banquet, and the Pappadopoli, a stifling labyrinth of plush and royal photographs, we took sanctuary from culture in Harry’s Bar. There was an ominous chatter, a quick-fire of greetings: the English are arriving.

In the evening we went back to Harry’s Bar, where our host regaled us with a drink compounded of champagne and cherry brandy. “To have the right effect,” said Harry confidentially, “it must be the worst cherry brandy.” It was.

Before this my acquaintance with our host was limited to the hunting field. He looked unfamiliar in a green beach vest and white mess jacket.

Venice, August 22nd.—In a gondola to San Rocco, where Tintoretto’s Crucifixion took away my breath; I had forgotten it. The old visitors’ book with Lenin’s name in it had been removed. At the Lido there was a breeze; the sea was rough, cool, and free from refuse.

We motored out to tea at Malcontenta, by the new road over the lagoons beside the railway. Nine years ago Landsberg found Malcontenta, though celebrated in every book on Palladio, at the point of ruin, doorless and windowless, a granary of indeterminate farm-produce. He has made it a habitable dwelling. The proportions of the great hall and state rooms are a mathematical paean. Another man would have filled them with so-called Italian furniture, antique-dealers’ rubbish, gilt. Landsberg has had the furniture made of plain wood in the local village. Nothing is “period” except the candles, which are necessary in the absence of electricity.

Outside, people argue over the sides and affect to deplore the back. The front asks no opinion. It is a precedent, a criterion. You can analyse it—nothing could be more lucid; but you cannot question it. I stood with Diane on the lawn below the portico, as the glow before dusk defined for one moment more clearly every stage of the design. Europe could have bid me no fonder farewell than this triumphant affirmation of the European intellect. “It’s a mistake to leave civilisation”, said Diane, knowing she proved the point by existing. I was lost in gloom.

Inside, the candles were lit and Lifar danced. We drove back through a rainstorm, and I went to bed with an alarm clock.

S.s.

1 comment