The merchant was not some ordinary grocer from whom the people bought clothes or spices – no! Nor did he keep company with the poor, common residents of his street. Day in and day out, he sat in his large study with the tall cabinets and long shelves and did his accounts and calculations. For his trade extended far across the seas to far-flung, distant lands. At intervals – perhaps once or twice per year – he had to leave his house for an extended period, when his business affairs summoned him far away. At these times, the girl stayed home by herself and took care of the household. One day the merchant-lord stood, once again, before the girl to tell her that he was leaving home for some time. ‘I don’t know when I will return,’ he said. ‘Take care of the house as you have before – but’, he interrupted himself, ‘I see you are old enough now; during my absence you can do as you please in the house. Here, take the keys.’ The girl, who up until this point had stood silently in front of him, gazing wide-eyed at the strange, colourful flowers that were embroidered onto the lord-merchant’s clothes, looked up and took the keys. Suddenly the merchant-lord looked at her with intent. Then he spoke in a stern tone of voice: ‘You know very well that you may use the keys only for the rooms in which you see to the household chores. Never let yourself be tempted to ascend to the upper floor. Do you understand?’ Timidly the girl assented. Then the merchant bowed down, kissed her, looked at her once more with a penetrating gaze, went down the stairs and left the house. The front door slammed shut behind him with a bang. The girl was still standing by the stairs in a daze, gazing at the large bundle of ancient keys that she held in her hand.

—

Translated by Sebastian Truskolaski.

Fragment written c. 1906–12; unpublished in Benjamin’s lifetime. Gesammelte Schriften VII, 635–6.

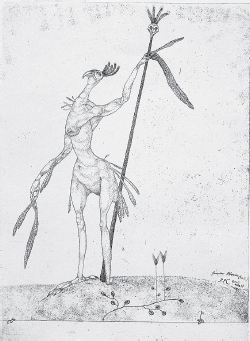

Aged Phoenix (Invention 9) (Greiser Phönix [Invention 9]), 1905.

ONLY FOR GROWN–UPS. NERVOUS TYPES – BEWARE!

Above the landscape hung such storm clouds as cause that specific fear of storms among young people known to physicians under a Latin name. It was a gently apprehensive mountain scenery. The path was steep and tiresome; the air was very hot and high temperatures prevailed. A mature man — greyed by the passing of the years – and an adolescent moved as inaudible points through the silence. They carried an empty stretcher. From time to time the gaze of the younger man fell upon the stretcher and his eyes would fill with tears. It was not long before a doleful song streamed forth from his mouth, reverberating from the mountain with a thousand sobs. ‘Red of the morning, red of the morning lights the path to an early death.’1 In the distance, bloody bolts of lightning tinged the sky. Suddenly the singing broke off and was followed by a faint groan. ‘Permit me for a moment’, the young man said to the elder one. He rested the stretcher on the ground, sat down, closed his eyes and folded his hands.

At the peak of the landscape we find him again. A ruin stood there, overgrown by the green of nature.

1 comment