This appears as fate and is a communion between body and the order of the world that is present in the story ‘The Lucky Hand’ and that Benjamin returns to again and again. But such a version of things does not send play completely into a mystical realm. And indeed the gambler may misjudge, may make a wrong move, a false play. As Benjamin states, ‘The ideal of the experience formed by shock is the catastrophe. In gambling this becomes very explicit; by persistently raising the stakes, in the hope of retrieving what is lost, the gambler steers toward total ruin.’51 For Benjamin, gambling, as well as fate, has its historical materialist side. One of the striking aspects of nineteenth-century capitalism, as represented in The Arcades Project, is its simultaneous naturalisation and mythologisation of social and historical forces as fate. This took on various forms, such as the language of a seemingly self-propellant rising and tumbling of stocks and shares – a consequence of the misconception (or ignorance) of the value-form, of playing the market, of prophecies of wide-scale destruction. Benjamin quotes from Paul Lafargue’s ‘The Causes of Belief in God’ (1906):

Today’s economic progress in general inclines ever more to transmute capitalist society into a colossal international gambling house, where the bourgeois wins and loses capital as a consequence of events which remain unknown to him … The ‘inscrutable’ is deified in bourgeois society just as it is in a gambling venue … Triumphs and losses, which are the result of causes that are unexpected, in the main indecipherable, and apparently reliant on chance, predispose the bourgeois to adopt the spiritual condition of the gambler … The capitalist, whose prosperity is bound up with stocks and shares, which are dependent on deviations in market value and yield whose causes he does not understand, is a professional gambler. The gambler, nonetheless … is a highly superstitious type. The habitués of gambling hells always possess magic spells to conjure up the Fates. One will mumble a prayer to Saint Anthony of Padua or some other spirit from the heavens; another will lay his bet only if a specific colour has won; while a third clasps a rabbit’s foot in his left hand; and so on. The inscrutable in society shrouds the bourgeois, just as the inscrutable in nature the savage.52

Play and playing, toys and mimicry: these crack open the world. But the impulse of play leads back to the dreamworld, to wishing and longing, to the gambler’s yearning to make the greatest win, and it leads back to the desires that both mitigate and make blind to the catastrophe of economic rule. In ‘Verdant Elements’, Benjamin celebrates the attitude of ‘exaggerated exuberance’ in a children’s learning primer written by Tom Seidmann-Freud. Such an attitude informs all of Benjamin’s works of fiction, be it the wild excesses of the early night-dreams and fantasies, the tall tales of wanderers and adventurers and the absurd reasoning in origin myths and riddles. Benjamin wrote the following of the consummate storyteller Proust: ‘He lay on his bed racked with homesickness, homesick for the world, distorted in the state of similarity, a world in which the true surrealist face of existence breaks through.’53 The same can perhaps be said of him and his own fictions.

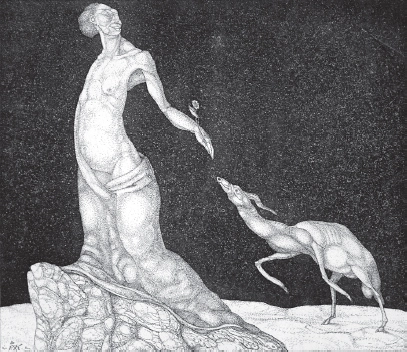

Woman and Beast (Weib und Tier), 1904.

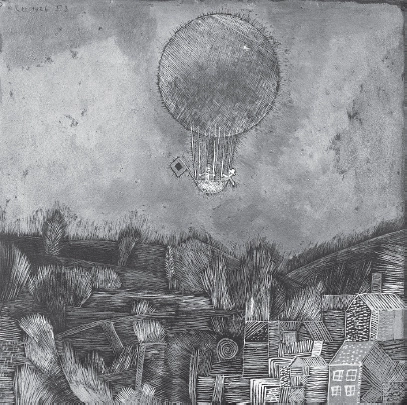

The Balloon (Der Luftballon), 1926.

The sky had spread out a select German summer night between the trees. But as during a rococo rendezvous, the moon emitted a discreet yet bright yellow. Curling blossoms trembled down from the trees into the dark moss like yellow strips of confetti. The gigantic outlines of the great literature pyramid towered in the blue darkness. It was cosily uncanny. And now it lay there. Its peak stood out against the clear sky. Shades of green and white – many colours – glowed delicately within the black mountain. E.T.A. Hoffmann shone from an undulating Baroque boulder that protruded half toppled from the mound. The moon illuminated him. At the bottom yawned a black gate. In the uncontrollable twilight, its pillars appeared like Doric columns, Iliad on the one, Odyssey on the other. A white marble staircase glowed halfway up the pyramid. Upon it moved, quick as a monkey, the silhouette of a thin little man who continually called out ‘Gottsched, Gottsched’ in an unspeakably bright voice … so quiet was his call that it was only audible in this fairy tale silence.

1 comment