In conversation with Ophelia, he shifts from light talk in verse to a passionate prose denunciation of women (3.1.103), though the shift to prose here is perhaps also intended to suggest the possibility of madness. (Consult Brian Vickers, The Artistry of Shakespeare’s Prose [1968].)

Poetry: Drama in rhyme in England goes back to the Middle Ages, but by Shakespeare’s day rhyme no longer dominated poetic drama; a finer medium, blank verse (strictly speaking, unrhymed lines of ten syllables, with the stress on every second syllable) had been adopted. But before looking at unrhymed poetry, a few things should be said about the chief uses of rhyme in Shakespeare’s plays. (1) A couplet (a pair of rhyming lines) is sometimes used to convey emotional heightening at the end of a blank verse speech; (2) characters sometimes speak a couplet as they leave the stage, suggesting closure; (3) except in the latest plays, scenes fairly often conclude with a couplet, and sometimes, as in Richard II, 2.1.145-46, the entrance of a new character within a scene is preceded by a couplet, which wraps up the earlier portion of that scene; (4) speeches of two characters occasionally are linked by rhyme, most notably in Romeo and Juliet, 1.5.95-108, where the lovers speak a sonnet between them; elsewhere a taunting reply occasionally rhymes with the previous speaker’s last line; (5) speeches with sententious or gnomic remarks are sometimes in rhyme, as in the duke’s speech in Othello (1.3.199-206); (6) speeches of sardonic mockery are sometimes in rhyme—for example, Iago’s speech on women in Othello (2.1.146-58)—and they sometimes conclude with an emphatic couplet, as in Bolingbroke’s speech on comforting words in Richard II (1.3.301-2); (7) some characters are associated with rhyme, such as the fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream; (8) in the early plays, especially The Comedy of Errors and The Taming of the Shrew, comic scenes that in later plays would be in prose are in jingling rhymes; (9) prologues, choruses, plays-within-the-play, inscriptions, vows, epilogues, and so on are often in rhyme, and the songs in the plays are rhymed.

Neither prose nor rhyme immediately comes to mind when we first think of Shakespeare’s medium: It is blank verse, unrhymed iambic pentameter. (In a mechanically exact line there are five iambic feet. An iambic foot consists of two syllables, the second accented, as in away; five feet make a pentameter line. Thus, a strict line of iambic pentameter contains ten syllables, the even syllables being stressed more heavily than the odd syllables. Fortunately, Shakespeare usually varies the line somewhat.) The first speech in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, spoken by Duke Theseus to his betrothed, is an example of blank verse:

Now, fair Hippolyta, our nuptial hour

Draws on apace. Four happy days bring in

Another moon; but, O, methinks, how slow

This old moon wanes! She lingers my desires,

Like to a stepdame, or a dowager,

Long withering out a young man’s revenue.

(1.1.1—6)

As this passage shows, Shakespeare’s blank verse is not mechanically unvarying. Though the predominant foot is the iamb (as in apace or desires), there are numerous variations. In the first line the stress can be placed on “fair,” as the regular metrical pattern suggests, but it is likely that “Now” gets almost as much emphasis; probably in the second line “Draws” is more heavily emphasized than “on,” giving us a trochee (a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one); and in the fourth line each word in the phrase “This old moon wanes” is probably stressed fairly heavily, conveying by two spondees (two feet, each of two stresses) the oppressive tedium that Theseus feels.

In Shakespeare’s early plays much of the blank verse is end-stopped (that is, it has a heavy pause at the end of each line), but he later developed the ability to write iambic pentameter verse paragraphs (rather than lines) that give the illusion of speech. His chief techniques are (1) enjambing, i.e., running the thought beyond the single line, as in the first three lines of the speech just quoted; (2) occasionally replacing an iamb with another foot; (3) varying the position of the chief pause (the caesura) within a line; (4) adding an occasional unstressed syllable at the end of a line, traditionally called a feminine ending; (5) and beginning or ending a speech with a half line.

Shakespeare’s mature blank verse has much of the rhythmic flexibility of his prose; both the language, though richly figurative and sometimes dense, and the syntax seem natural. It is also often highly appropriate to a particular character. Consider, for instance, this speech from Hamlet, in which Claudius, King of Denmark (“the Dane”), speaks to Laertes:

And now, Laertes, what’s the news with you?

You told us of some suit. What is‘t, Laertes?

You cannot speak of reason to the Dane

And lose your voice. What wouldst thou beg, Laertes,

That shall not be my offer, not thy asking?

(1.2.42-46)

Notice the short sentences and the repetition of the name “Laertes,” to whom the speech is addressed. Notice, too, the shift from the royal “us” in the second line to the more intimate “my” in the last line, and from “you” in the first three lines to the more intimate “thou” and “thy” in the last two lines. Claudius knows how to ingratiate himself with Laertes.

For a second example of the flexibility of Shakespeare’s blank verse, consider a passage from Macbeth. Distressed by the doctor’s inability to cure Lady Macbeth and by the imminent battle, Macbeth addresses some of his remarks to the doctor and others to the servant who is arming him. The entire speech, with its pauses, interruptions, and irresolution (in “Pull’t off, I say,” Macbeth orders the servant to remove the armor that the servant has been putting on him), catches Macbeth’s disintegration. (In the first line, physic means “medicine,” and in the fourth and fifth lines, cast the water means “analyze the urine.”)

Throw physic to the dogs, I’ll none of it.

Come, put mine armor on. Give me my staff.

Seyton, send out.—Doctor, the thanes fly from me.—

Come, sir, dispatch. If thou couldst, doctor, cast

The water of my land, find her disease

And purge it to a sound and pristine health,

I would applaud thee to the very echo,

That should applaud again.—Pull’t off, I say.—

What rhubarb, senna, or what purgative drug,

Would scour these English hence? Hear‘st thou of them?

(5.3.47-56)

Blank verse, then, can be much more than unrhymed iambic pentameter, and even within a single play Shakespeare’s blank verse often consists of several styles, depending on the speaker and on the speaker’s emotion at the moment.

The Play Text as a Collaboration

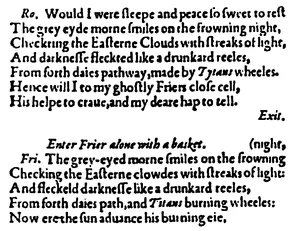

Shakespeare’s fellow dramatist Ben Jonson reported that the actors said of Shakespeare, “In his writing, whatsoever he penned, he never blotted out line,” i.e., never crossed out material and revised his work while composing. None of Shakespeare’s plays survives in manuscript (with the possible exception of a scene in Sir Thomas More), so we cannot fully evaluate the comment, but in a few instances the published work clearly shows that he revised his manuscript. Consider the following passage (shown here in facsimile) from the best early text of Romeo and Juliet, the Second Quarto (1599):

Romeo rather elaborately tells us that the sun at dawn is dispelling the night (morning is smiling, the eastern clouds are checked with light, and the sun’s chariot—Titan’s wheels—advances), and he will seek out his spiritual father, the Friar. He exits and, oddly, the Friar enters and says pretty much the same thing about the sun. Both speakers say that “the gray-eyed morn smiles on the frowning night,” but there are small differences, perhaps having more to do with the business of printing the book than with the author’s composition: For Romeo’s “checkring,” “fleckted,” and “pathway,” we get the Friar’s “checking,” “fleckeld,” and “path.” (Notice, by the way, the inconsistency in Elizabethan spelling: Romeo’s “clouds” become the Friar’s “clowdes.”)

Both versions must have been in the printer’s copy, and it seems safe to assume that both were in Shakespeare’s manuscript. He must have written one version—let’s say he first wrote Romeo’s closing lines for this scene—and then he decided, no, it’s better to give this lyrical passage to the Friar, as the opening of a new scene, but he neglected to delete the first version. Editors must make a choice, and they may feel that the reasonable thing to do is to print the text as Shakespeare intended it.

1 comment