That was one of the many ways in which Yeats designed not just individual volumes of poems but his collected poems as a whole. He liked, too, to end poems and sometimes bigger units with questions rather than with answers, as though to instigate the continuation of writing in his next volume. We might call that form of closure really “anticlosure,” since it holds things open rather than shuts them off. Yeats did that for a number of his major lyrics, including “Among School Children” with its dancer and dance, or “Leda and the Swan” with its dilemma about knowledge and power.

Passing over the wonderful Crazy Jane poems, based on an actual old woman called Cracked Mary who lived near Yeats’s tower and Lady Gregory’s Coole Park, I press on to the second ending of the volume, the final poem of the “Words for Music Perhaps” sequence. Entitled “The Delphic Oracle upon Plotinus,” its two five-line stanzas depict the Delphic Oracle’s answer to the question of what happened to the third-century Neoplatonic philosopher Plotinus after his death:

Behold that great Plotinus swim

Buffeted by such seas;

Bland Rhadamanthus beckons him,

But the Golden Race looks dim,

Salt blood blocks his eyes.

Scattered on the level grass

Or winding through the grove

Plato there and Minos pass,

There stately Pythagoras

And all the choir of Love.

Yeats stays close here to the wording of his source, a translation by Stephen MacKenna, himself a friend of Synge, John O’Leary, Maud Gonne, and Yeats himself. It reads in part: “where Minos and Rhadamanthus dwell, great brethren of the golden race of mighty Zeus, where dwells the just Aeacus, and Plato, consecrated power, and stately Pythagoras, and all the choir of Immortal Love.” But Yeats does not show Plotinus actually in the paradise, but only swimming there through the seas of life. The salt blood of life blocks his vision, but the immortals send an intense shaft of light so that he can see the vision even while immersed in the distractions of life. Yeats would later treat the same scene more satirically in the lyric “News for the Delphic Oracle,” from Last Poems, where the “golden race” have become “golden codgers” instead and everybody lies around “sighing” in the Neoplatonic paradise while vitality lives on in the sensual and sexual world of Pan. But here Yeats treats the myth respectfully and admires the struggle of Plotinus to maintain glimpses of the eternal in the seas of transitory nature. Significantly, Yeats includes a date for this poem, 1931, just as he had for “Sun and Stream at Glendalough,” which he dated 1932, as though to stress yet again that the poems in this volume do not appear in chronological order but in a different one.

Yeats had not finished his series of conclusions with “The Delphic Oracle upon Plotinus” but instead bestowed that honor on the final poem of the sequence, “A Woman Young and Old.” “From the ‘Antigone,’” as we have seen, occupies some of the same working manuscript pages as the very first poem of the entire collection, “In Memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Con Markiewicz.” It helps to remember the story of Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone, last of his Oresteia trilogy, in which after Oedipus’ tragic exile from Thebes his sons Eteocles and Polyneices fall into civil war in which both die over the kingship. When the new king, Creon, refuses to bury Polyneices, his sister Antigone does so instead, for which Creon condemns her to death by burial alive in a cave. Yeats’s poem adapts a chorus about Antigone’s forthcoming death. Here is the poem, the last one in the volume. The quatrain structure of its sixteen lines would have come across more regularly had Yeats’s friend and former secretary Ezra Pound not persuaded him to relocate in typescript the original eighth line, “Inhabitant of the soft cheek of a girl,” to the second line, thus disrupting the intended abab rhyme scheme:

Overcome—O bitter sweetness,

Inhabitant of the soft cheek of a girl—

The rich man and his affairs,

The fat flocks and the fields’ fatness,

Mariners, rough harvesters;

Overcome Gods upon Parnassus;

Overcome the Empyrean; hurl

Heaven and Earth out of their places,

That in the same calamity

Brother and brother, friend and friend,

Family and family,

City and city may contend,

By that great glory driven wild.

Pray I will and sing I must,

And yet I weep—Oedipus’ child

Descends into the loveless dust.

In the Greek play, the chorus intends these lines to critique the disruptive power of love to destabilize social, religious, and moral hierarchies, whereas Yeats clearly praises Antigone’s action and approves of it. We may ask, why does Yeats criticize the political commitments of the Gore-Booth sisters at the beginning but praise those of Antigone at the end? After all, they both give their lives to political causes. Surely the answer has something to do with what “Coole and Ballylee, 1931” called “traditional sanctity and loveliness.” Antigone upholds those traditional and cultural values, whereas in Yeats’s view the Gore-Booth sisters betray them. In that way, Antigone stands with Lady Gregory’s devotion to the values of Coole, in contrast to Eva and Con’s abandonment of the similar ones of Lissadell. That becomes especially pertinent when we recall that Antigone’s Greece had just passed through a civil war, as had Coole, Lissadell, and the rest of Ireland only a few years before Yeats wrote his poem. He takes his stand with the concrete and imaginative rather than the abstract and mechanical, and ends the volume with a particular image of a particular young woman.

But not altogether. As so often (think of the poem “Politics” at the end of the Collected Poems), Yeats ends with his own relation as poet to such matters, and with his own compulsion for continued speech. Separated by a space break on the page from the first line of its own quatrain, the concluding three lines (“Pray I will...”) become a tercet on the poet’s situation.

Note the sequencing of the three verbs describing the poet’s action. First, he will pray, in accord with the values of traditional sanctity. Second, he then sings, or continues to be a poet. Yet even while doing so, he weeps at the tragedy of life. This is a different sort of ending from those images in “All Souls’ Night” that conclude the Tower volume. Here, as in “The Circus Animals’ Desertion,” the poet plunges back into the human heart again, where all the ladders start. In a final turn, the poet then leaves us with the image not of himself but of Antigone, as she courageously descends to meet her fate. And that finally is what Yeats gives us, and what The Winding Stair and Other Poems gives us—the impetus to go on and to go forward, in his poetry and in our own lives. It is an ending that defies closure, as Yeats at his best so often does.

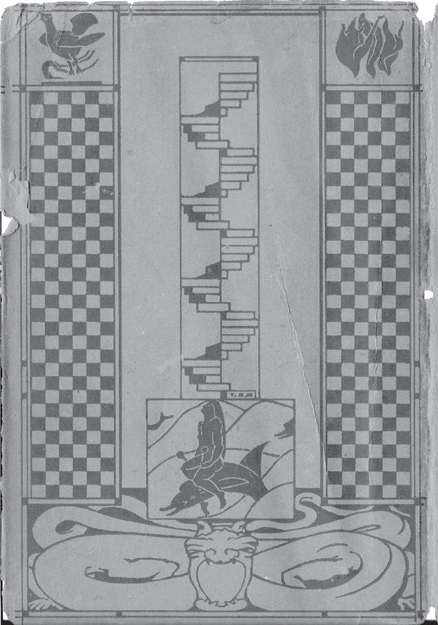

7. Sturge Moore’s Jacket and Cover Design for

The Winding Stair and other Poems.

THE WINDING STAIR AND OTHER POEMS

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA • MADRAS

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO

DALLAS • ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

OF CANADA, LIMITED

TORONTO

NOTES

The French-born artist, musician, and designer Edmund Dulac (1882–1953) met Yeats shortly after moving to London in 1904 and became a lifelong friend. Known particularly for his book illustrations, Dulac contributed both book and theater designs for Yeats’s work, such as the Japanese Noh-influenced Four Plays for Dancers (1921), which included the play At the Hawk’s Well, in which the Irish hero Cuchulain seeks to drink from the water of immortality.

1 comment