At that time he also designed a collection of wallpapers based upon the pictures for Katzenbach and Warren of New York.

Bilignin

Par Belley

Ain

My dear Clement Hurd,

I am awfully pleased about the wall paper, once we did very good wall paper of the pigeons on the grass and we have it in two rooms in Paris and it would be lovely to have another with the World is Round, and the rugs, the window sounds perfectly ravishing and everybody has been so xcited about the ad in the New Yorker, that they all send me a copy, I cannot tell you how pleased I am about it all, and your business arrangements are perfectly satisfactory. It may be that we will come over in the early spring, nothing of course is certain but it is possible and it will then be a very great pleasure our meeting, it would be fun too if they filmed us, it would be fun and lucrative and most xciting, we are living peacefully here in the country, and I am working a lot, so once more to the pleasure of meeting either there or here, always

Gtde St

Of course we were very excited at the prospect of meeting Gertrude Stein, but by 1940 the war had already begun in Europe, and with the attack on Pearl Harbor and the entrance of the United States into the conflict, our hopes were dashed. Neither the Scotts, John McCullough, nor my husband and I were ever to meet the famous expatriate.

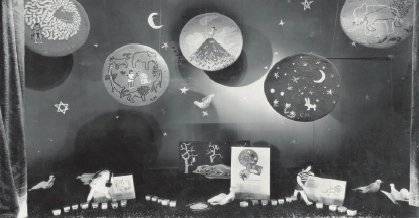

Clement Hurd’s rugs displayed at W. & J. Sloane, New York, 1939.

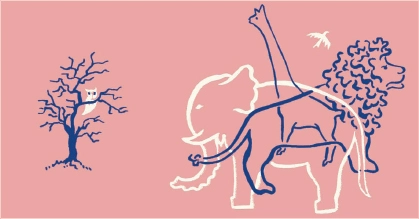

A fragment of the wallpaper designed by Clement Hurd for Katzenbach and Warren, New York, 1940.

Two other letters from Gertrude Stein rounded out the exchange between her and Clement Hurd.

Bilignin

Par Belley

Ain

My dear Hurd,

You will be pleased that the first child who has told me about our book is a little French boy six years old the son of a captain in the Army and our proprietor, I gave them the book not thinking as none of them read English that it would be anything but a souvenir. But I saw little Francis and much xcited he said to me tell me more about Rose and the mountain and Willy and the Lion, I said how did you know about them it would seem that he was mad about the illustrations and a friend who read English came in and told him the stories, and he adores the book, he says he would like another one by us about not wild animals mts., but about poplar trees and birds and rabbits and deer and gazelle and if we wanted to a wild boar, a big one or a little one I asked him, a medium sized one he said. And when I told him that there was wall paper to be of it his eyes just grew large and round, do send me a bit of it so that I can see what it looks like, it looks as if it would be a double happy New Year to you and Mrs. Hurd now and always

Gtde St

[Postmarked Ain]

My dear Clement Hurd,

I have just received the samples of the wall paper and we are all delighted with them we took them over to Beau[?] where Rose lives and the family were enchanted, I am not sure I do not like the blue one best but then when I say that I look at the other and am not sure, if they do a room of it and with the rugs you have a photograph of it do send it to me. How are the rugs selling, I have heard nothing about the Christmas sale, have you, and now have you heard of the new children’s book that I am doing, I might say have done, because it is pretty nearly finished, it is a book about Alphabets and birthdays, a lot of little stories to illustrate it and I want it sombre and xciting, the way Gustave Doré’s illustrations were to me when I was a child, I suggested that the book be done in black and gold gold paper and black print or the other way, but perhaps you could think of a combination of colors that would be more sombre and xciting, all this of course, if McCullough likes the book and if you are to do the illustrations, I do not mind if you make it even a little frightening, well anyway I will be sending the ms. along in about ten days now and I hope you will like it

Always

Gtde St

THEIR delightful correspondence now resides in the Beinecke Library at Yale University. Throughout these letters from Bilignin, Gertrude Stein showed herself to be a most sensitive and appreciative person whose writing style in a letter has the intimacy and immediacy of conversation.

It was Stein’s reputation for unintelligibility that caused an outcry of disbelief when in the spring of 1939 Young Scott Books announced that it would publish a children’s book by her. Some commentators sharpened their stilettos and attacked with the skepticism they held in reserve for such a production. “The book will have a social will have a social will have a social aspect in as much as it is being published by William R. Scott,” stuttered one, digging at both author and publisher. Another, attempting cleverness, burbled “Gertrude Stein is writing is writing is writing a new Gertrude Stein a new book is writing is writing Gertrude a new a new a new. . . .” In a short piece entitled “Stein Song” the New York Post stuffily editorialized that “Gertrude Stein has written a story for children called The World Is Round. However, the book may be expected to prove the world is square, since she is the same Gertrude Stein who wrote Four Saints in Three Acts.”

When the book appeared in the fall of 1939, the negative reviews minced no words. “Far, far better,” wrote Dorothy Killgallen, “if you have a child, to let him read Nick Carter, William Saroyan, the Wizard of Oz, Tommy Manville’s Diary, or the menu at Lindy’s—anything but such literary baby-talk.”

Actually, most reviewers were charmed by both the writing and the illustrations. Catherine MacKenzie in the New York Times cautiously stated that the familiar style and rhythm of Gertrude Stein were easily accessible to little children, who “if they are not laughed or ridiculed out of it, have a grand time with the sound of words.”

In the New York Herald Tribune, May Lamberton Becker, one of the most discerning reviewers of children’s books, objected only to the pink color of the paper. Recounting a story of some twenty adults who read the book aloud to each other, she concluded: “It was an afternoon of the sort of happiness that cleanses the mind—a child’s happiness.” Refusing to take potshots at Stein by quoting nonsensical lines, she added, “You cannot judge it by extracts any more than you can judge a movie by stills.”

In an article in the New York Times Book Review of November 12, 1939, Ellen Lewis Buell seriously attempted to analyze why the book was so successful: “For a skeptic who never quite finished the first paragraph of Tender Buttons, it is a pleasant duty to report that Miss Stein seems to have found her audience, possibly a larger one than usual, certainly a more appreciative one. As to just why, it would take an expert in the subconscious and a corps of child psychologists fully to determine. Not the intoxication of words which ‘keep tumbling into rhyme,’ as one little girl neatly described it; not the irresistible rhythm of such songs as ‘Bring me bread, bring me butter,’ and ‘Round is around,’ nor the fun which flashes out when least expected, can fully explain its success. Perhaps it is because, in addition to these virtues, Miss Stein has caught within this architectural structure of words which rhyme and rhyme again the essence of certain moods of childhood: the first exploration of one’s own personality, the feeling of a lostness in a world of night skies and mountain peaks, sudden unreasoning emotions and impulses, the preoccupation with vagrant impressions of little things filtering through the mind.

“It is meant to be read aloud, a little at a time, and the adult who does so will find himself saying ‘I remember thinking like this,’ and succumbing to the seductive quality of phrases, which will make it probably the most quotable book of the season. For children, apparently, there is a real fascination in the moods of Rose, pondering over the phenomenon of self—‘would she have been Rose if her name had not been rose’; and in Willie, so sure of his own individuality, and in the lion, which was not blue, who wanders in and out of the chapters with a blithe disregard for the proper chronology. The response to it is as various as it is individual. One child says bluntly, ‘It’s cuckoo crazy’; a six-year-old boy has listened to it a score of times, and one little girl says, ‘I like it because when you start thinking about it you never get anywhere. It just keeps going along.’

“It is printed in blue ink, because that was Rose’s favorite color, on fiercely pink paper, as toothsome-looking as ten-cent store candy. It is hard on the eyes, but to children it is beautiful, and certainly Clement Hurd’s drawings, which translate something of Rose’s own feeling of the vastness of space and infinity into beautifully contrived decorations, are delightful.”

The World Is Round was published in an edition of 3,000 copies, of which one hundred were specially bound and presented in a slipcase and were signed by the author and illustrator. The regular edition was priced at $2.50 and the special copies were $5.00. Bill Scott recognized the potential of having a best seller in The World Is Round, and hired a PR man to handle publicity. Hundreds of review copies were sent out, one to almost every newspaper that had a book column. Notices appeared in newspapers all across America.

1 comment