Their Finest Hour Read Online

| Moral of the Work |

In War: Resolution

In Defeat: Defiance

In Victory: Magnanimity

In Peace: Good Will

| Theme of the Volume |

How the British people

held the fort

ALONE

till those who

hitherto had been half blind

were half ready

|

Book One

The Fall of France

| 1 |

The Beginning and the End — The Magnitude of Britain’s Work for the Common Cause — Divisions in Contact with the Enemy Throughout the War — The Roll of Honour — The Share of the Royal Navy — British and American Discharge of Air Bombs — American Aid in Munitions Magnifies Our War Effort — Formation of the New Cabinet — Conservative Loyalty to Mr. Chamberlain — The Leadership of the House of Commons — Heresy-hunting Quelled in Due Course — My Letter to Mr. Chamberlain of May 11 — A Peculiar Experience — Forming a Government in the Heat of Battle — New Colleagues: Clement Attlee, Arthur Greenwood, Archibald Sinclair, Ernest Bevin, Max Beaverbrook — A Small War Cabinet — Stages in the Formation of the Government, May 10 to May 16 — A Digression on Power — Realities and Appearances in the New War Direction — Alterations in the Responsibilities of the Service Ministers — War Direction Concentrated in Very Few Hands — My Personal Methods — The Written Word — Sir Edward Bridges — My Relations with the Chiefs of the Staff Committee — General Ismay — Kindness and Confidence Shown by the War Cabinet — The Office of Minister of Defence — Its Staff: Ismay, Hollis, Jacob — No Change for Five Years — Stability of Chiefs of Staff Committee — No Changes from 1941 till 1945 Except One by Death — Intimate Personal Association of Politicians and Soldiers at the Summit — The Personal Correspondence — My Relations with President Roosevelt — My Message to the President of May 15 — “Blood, Toil, Tears, and Sweat.”

NOW AT LAST the slowly gathered, long-pent-up fury of the storm broke upon us. Four or five millions of men met each other in the first shock of the most merciless of all the wars of which record has been kept. Within a week the front in France, behind which we had been accustomed to dwell through the long years of the former war and the opening phase of this, was to be irretrievably broken. Within three weeks the long-famed French Army was to collapse in rout and ruin, and the British Army to be hurled into the sea with all its equipment lost. Within six weeks we were to find ourselves alone, almost disarmed, with triumphant Germany and Italy at our throats, with the whole of Europe in Hitler’s power, and Japan glowering on the other side of the globe. It was amid these facts and looming prospects that I entered upon my duties as Prime Minister and Minister of Defence and addressed myself to the first task of forming a Government of all parties to conduct His Majesty’s business at home and abroad by whatever means might be deemed best suited to the national interest.

Five years later almost to a day it was possible to take a more favourable view of our circumstances. Italy was conquered and Mussolini slain. The mighty German Army surrendered unconditionally. Hitler had committed suicide. In addition to the immense captures by General Eisenhower, nearly three million German soldiers were taken prisoners in twenty-four hours by Field Marshal Alexander in Italy and Field Marshal Montgomery in Germany. France was liberated, rallied and revived. Hand in hand with our allies, the two mightiest empires in the world, we advanced to the swift annihilation of Japanese resistance. The contrast was certainly remarkable. The road across these five years was long, hard, and perilous. Those who perished upon it did not give their lives in vain. Those who marched forward to the end will always be proud to have trodden it with honour.

* * * * *

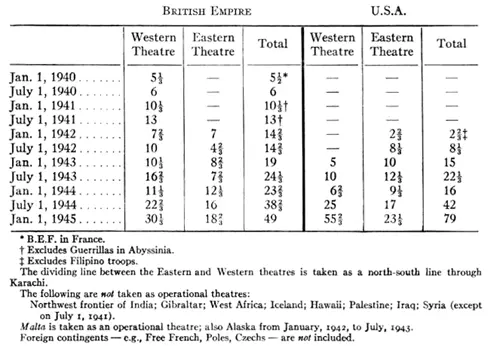

LAND FORCES IN FIGHTING CONTACT WITH THE ENEMY

“EQUIVALENT DIVISIONS”

In giving an account of my stewardship and in telling the tale of the famous National Coalition Government, it is my first duty to make plain the scale and force of the contribution which Great Britain and her Empire, whom danger only united more tensely, made to what eventually became the common cause of so many states and nations. I do this with no desire to make invidious comparisons or rouse purposeless rivalries with our greatest ally, the United States, to whom we owe immeasurable and enduring gratitude. But it is to the combined interest of the English-speaking world that the magnitude of the British war-making effort should be known and realised. I have therefore had a table made which I print on this page, which covers the whole period of the war. This shows that up till July, 1944, Britain and her Empire had a substantially larger number of divisions in contact with the enemy than the United States. This general figure includes not only the European and African spheres, but also all the war in Asia against Japan. Up till the arrival in Normandy in the autumn of 1944 of the great mass of the American Army, we had always the right to speak at least as an equal and usually as the predominant partner in every theatre of war except the Pacific and Australasian; and this remains also true, up to the time mentioned, of the aggregation of all divisions in all theatres for any given month. From July, 1944, the fighting front of the United States, as represented by divisions in contact with the enemy, became increasingly predominant, and so continued, mounting and triumphant, till the final victory ten months later.

Another comparison which I have made shows that the British and Empire sacrifice in loss of life was even greater than that of our valiant ally. The British total dead, and missing, presumed dead, of the armed forces, amounted to 303,240, to which should be added over 109,000 from the Dominions, India, and the colonies, a total of over 412,240. This figure does not include 60,500 civilians killed in the air raids on the United Kingdom, nor the losses of our merchant navy and fishermen, which amounted to about 30,000. Against this figure the United States mourn the deaths in the Army and Air Force, the Navy, Marines, and Coastguard, of 322,188.* I cite these sombre rolls of honour in the confident faith that the equal comradeship sanctified by so much precious blood will continue to command the reverence and inspire the conduct of the English-speaking world.

On the seas the United States naturally bore almost the entire weight of the war in the Pacific, and the decisive battles which they fought near Midway Island, at Guadalcanal, and in the Coral Sea in 1942 gained for them the whole initiative in that vast ocean domain, and opened to them the assault of all the Japanese conquests, and eventually of Japan herself. The American Navy could not at the same time carry the main burden in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

1 comment