Early the next morning, May 27, emergency measures were taken to find additional small craft “for a special requirement.” This was no less than the full evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force. It was plain that large numbers of such craft would be required for work on the beaches, in addition to bigger ships which could load in Dunkirk Harbour. On the suggestion of Mr. H. C. Riggs, of the Ministry of Shipping, the various boatyards, from Teddington to Brightlingsea, were searched by Admiralty officers, and yielded upwards of forty serviceable motor-boats or launches, which were assembled at Sheerness on the following day. At the same time lifeboats from liners in the London docks, tugs from the Thames, yachts, fishing-craft, lighters, barges, and pleasure-boats – anything that could be of use along the beaches – were called into service. By the night of the 27th a great tide of small vessels began to flow towards the sea, first to our Channel ports, and thence to the beaches of Dunkirk and the beloved Army.

The Admiralty did not hesitate to give full rein to the spontaneous movement which swept the seafaring population of our south and southeastern shores. Everyone who had a boat of any kind, steam or sail, put out for Dunkirk, and the preparations, fortunately begun a week earlier, were now aided by the brilliant improvisation of volunteers on an amazing scale. The numbers arriving on the 29th were small, but they were the forerunners of nearly four hundred small craft which from the 31st were destined to play a vital part by ferrying from the beaches to the off-lying ships almost a hundred thousand men. In these days I missed the head of my Admiralty map room, Captain Pim, and one or two other familiar faces. They had got hold of a Dutch schuit which in four days brought off eight hundred soldiers. Altogether there came to the rescue of the Army under the ceaseless air bombardment of the enemy about eight hundred and fifty vessels, of which nearly seven hundred were British and the rest Allied.

* * * * *

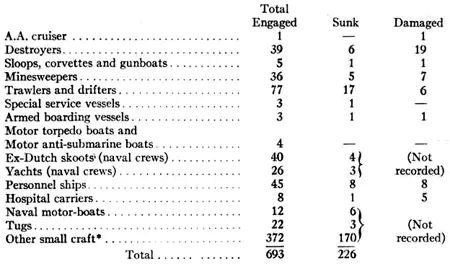

Here is the official list in which ships not engaged in embarking troops are omitted:

BRITISH SHIPS

ALLLIED SHIPS

* * * * *

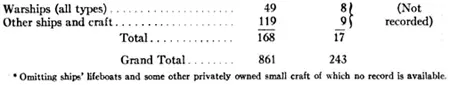

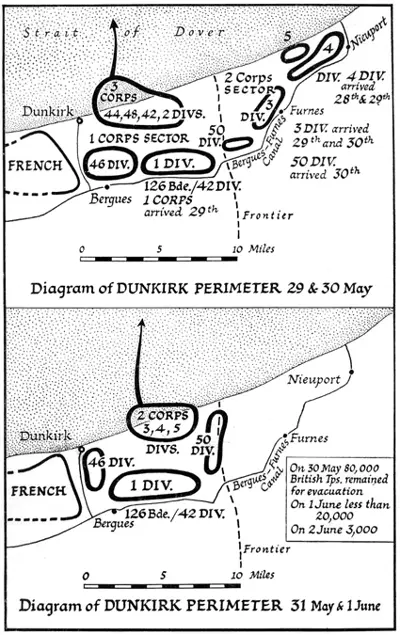

Meanwhile ashore around Dunkirk the occupation of the perimeter was effected with precision. The troops arrived out of chaos and were formed in order along the defences, which even in two days had grown. Those men who were in best shape turned about to form the line. Divisions like the 2d and 5th, which had suffered most, were held in reserve on the beaches and were then embarked early. In the first instance there were to be three corps on the front, but by the 29th, with the French taking a greater share in the defences, two sufficed. The enemy had closely followed the withdrawal, and hard fighting was incessant, especially on the flanks near Nieuport and Bergues. As the evacuation went on, the steady decrease in the number of troops, both British and French, was accompanied by a corresponding contraction of the defence. On the beaches among the sand dunes, for three, four, or five days scores of thousands of men dwelt under unrelenting air attack. Hitler’s belief that the German Air Force would render escape impossible, and that therefore he should keep his armoured formations for the final stroke of the campaign, was a mistaken but not unreasonable view.

Three factors falsified his expectations. First, the incessant air-bombing of the masses of troops along the seashore did them very little harm. The bombs plunged into the soft sand, which muffled their explosions. In the early stages, after a crashing air raid, the troops were astonished to find that hardly anybody had been killed or wounded. Everywhere there had been explosions, but scarcely anyone was the worse. A rocky shore would have produced far more deadly results. Presently the soldiers regarded the air attacks with contempt. They crouched in the sand dunes with composure and growing hope. Before them lay the grey but not unfriendly sea. Beyond, the rescuing ships and – Home.

The second factor which Hitler had not foreseen was the slaughter of his airmen.

1 comment