By trying to hold on till tomorrow we may lose all. By going tonight much may certainly be saved, though much will be lost. Nothing like numbers of effective French troops you mention believed in bridgehead now, and we doubt whether such large numbers remain in area. Situation cannot be fully judged by Admiral Abrial in the fortress, nor by you, nor by us here. We have therefore ordered General Alexander, commanding British sector of bridgehead, to judge, in consultation with Admiral Abrial, whether to try to stay over tomorrow or not. Trust you will agree.

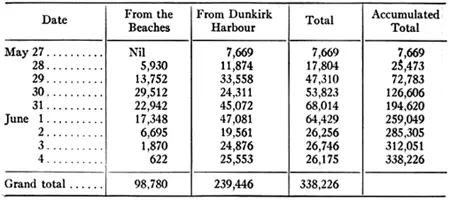

May 31 and June 1 saw the climax though not the end at Dunkirk. On these two days over 132,000 men were safely landed in England, nearly one-third of them having been brought from the beaches in small craft under fierce air attack and shell fire. On June 1 from early dawn onward the enemy bombers made their greatest efforts, often timed when our own fighters had withdrawn to refuel. These attacks took heavy toll of the crowded shipping, which suffered almost as much as in all the previous week. On this single day our losses by air attack, by mines, E-boats, or other misadventure were thirty-one ships sunk and eleven damaged.

The final phase was carried through with much skill and precision. For the first time it became possible to plan ahead instead of being forced to rely on hourly improvisations. At dawn on June 2, about four thousand British with seven antiaircraft guns and twelve anti-tank guns remained with the considerable French forces holding the contracting perimeter of Dunkirk. Evacuation was now possible only in darkness, and Admiral Ramsay determined to make a massed descent on the harbour that night with all his available resources. Besides tugs and small craft, forty-four ships were sent that evening from England, including eleven destroyers and fourteen minesweepers. Forty French and Belgian vessels also participated. Before midnight the British rearguard was embarked.

This was not, however, the end of the Dunkirk story. We had been prepared to carry considerably greater numbers of French that night than had offered themselves. The result was that when our ships, many of them still empty, had to withdraw at dawn, great numbers of French troops, many still in contact with the enemy, remained ashore. One more effort had to be made. Despite the exhaustion of ships’ companies after so many days without rest or respite, the call was answered. On June 4, 26,175 Frenchmen were landed in England, over 21,000 of them in British ships.

BRITISH AND ALLIED TROOPS LANDED IN ENGLAND

Finally, at 2.23 P.M. that day the Admiralty in agreement with the French announced that “Operation Dynamo” was now completed.

* * * * *

Parliament assembled on June 4, and it was my duty to lay the story fully before them both in public and later in secret session. The narrative requires only a few extracts from my speech, which is extant. It was imperative to explain not only to our own people but to the world that our resolve to fight on was based on serious grounds, and was no mere despairing effort. It was also right to lay bare my own reasons for confidence.

We must be very careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations. But there was a victory inside this deliverance, which should be noted. It was gained by the Air Force. Many of our soldiers coming back have not seen the Air Force at work; they saw only the bombers which escaped its protective attack. They underrate its achievements.

1 comment