The vast reach of the lake and this double mountain view go far to make Burlington a supremely beautiful town. I know of it only so much as I learned in an hour’s stroll, after my arrival. The lower portion by the lake-side is savagely raw and shabby, but as it ascends the long hill, which it partly covers, it gradually becomes the most truly charming, I fancy, of New England country towns. I followed a long street which leaves the hotel, crosses a rough, shallow ravine, which seems to divide it from the ugly poorness of the commercial quarter, and ascends a stately, shaded, residential avenue to no less a pinnacle of dignity than the University of Vermont. The university is a plain red building, with a cupola of beaten tin, shining like the dome of a Greek church, modestly embowered in scholastic shade—shade as modest as the number of its last batch of graduates, which I wouldn’t for the world repeat. It faces a small enclosed and planted common; the whole spot is full of civic greenness and stillness and sweetness. It pleased me deeply, considering what it was; it reminded me the least bit in the world of a sort of primitive development of an English cathedral close. On the summit of the hill, where it leaves the town, you embrace the whole circling presence of the distant mountains; you see Mount Mansfield looking over lake and land at Mount Marcy. Equally with the view, though—I had been having views all day—I enjoyed, as I passed again along the avenue, the pleasant, solid American homes, with their blooming breadth of garden, sacred with peace and summer and twilight. I say “solid” with intent; the most of them seemed to have been tested and ripened by time. One of them there was—but of it I shall say nothing. I reserve it for its proper immortality in the first chapter of the great American novel. It perhaps added a touch to my light impression of the old and the graceful that, as I wandered back to my hotel in the dusk, I heard repeatedly, as the homefaring laborers passed me in couples, the sound of a tongue of other than Yankee inflections. It was Canadian French.

NEWPORT

September 5, 1870

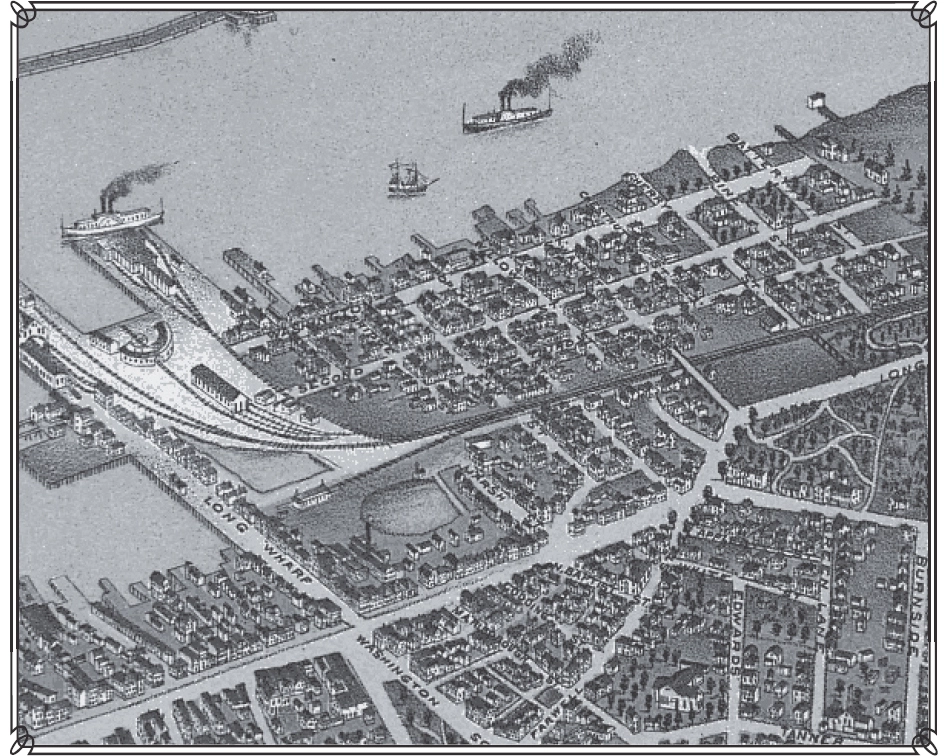

The Point, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1878.

THE SEASON AT NEWPORT HAS AN OBSTINATE LIFE. September has fairly begun, but as yet there is small visible diminution in the steady stream—the splendid, stupid stream—of carriages which rolls in the afternoon along the Avenue. There is, I think, a far more intimate fondness between Newport and its frequenters than that which in most American watering-places consecrates the somewhat mechanical relation between the visitors and the visited. This relation here is for the most part slightly sentimental. I am very far from professing a cynical contempt for the gaieties and vanities of Newport life: they are, as a spectacle, extremely amusing; they are full of a certain warmth of social color which charms alike the eye and the fancy; they are worth observing, if only to conclude against them; they possess at least the dignity of all extreme and emphatic expressions of a social tendency; but they are not so far from “was uns alle bändigt, das Gemeine” that I do not seem to overhear at times the still, small voice of this tender sense of the sweet, superior beauty of the local influences that surround them, pleading gently in their favor to the fastidious critic. I feel almost warranted in saying that here this exquisite natural background has sunk less in relative value and suffered less from the encroachments of pleasure-seeking man than the scenic properties of any other great watering-place. For this, perhaps, we may thank rather the modest, incorruptible integrity of the Newport landscape than any very intelligent forbearance on the part of the summer colony. The beauty of this landscape is so subtle, so essential, so humble, so much a thing of character and impression, so little a thing of feature and pretension, that it cunningly eludes the grasp of the destroyer or the reformer, and triumphs in impalpable purity even when it seems to condescend. I have sometimes wondered in sternly rational moods why it is that Newport is so loved of the votaries of idleness and pleasure. Its resources are few in number. It is emphatically circumscribed. It has few drives, few walks, little variety of scenery. Its charms and its interest are confined to a narrow circle. It has of course the unlimited ocean, but seafaring idlers are of necessity the fortunate few. Last evening, it seemed to me, as I drove along the Avenue, that my wonderment was quenched for ever.

1 comment