You feel here not more a man, perhaps, but more a passive gentleman and worldling. How sensible they ought to be, the denizens of these pleasant places, of their peculiar felicity and distinction! How it should purify their tempers and refine their intellects! How delicate, how wise, how discriminating they should become! What excellent manners and fancies their situation should generate! How it should purge them of vulgarity! Happy villeggianti of Newport!

NIAGARA

September 28, 1871

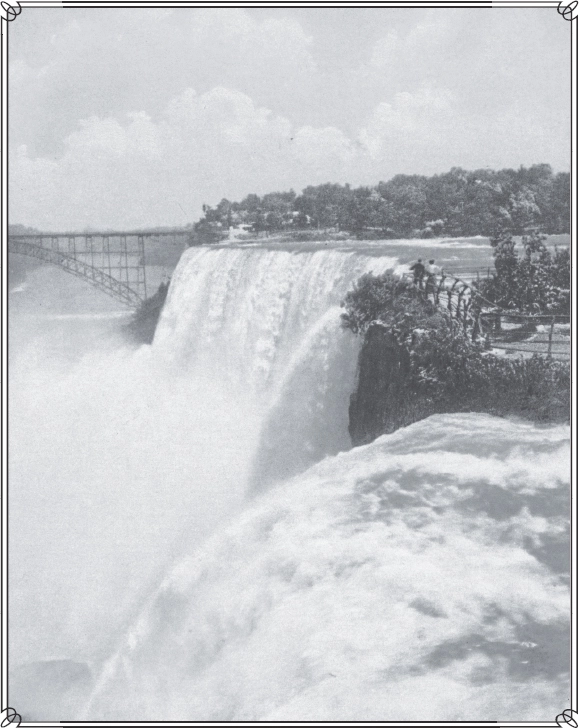

American Falls from Goat Island, Niagara, New York.

I.

My journey hitherward by a morning’s sail from Toronto across Lake Ontario, seemed to me, as regards a certain dull vacuity in this episode of travel, a kind of calculated preparation for the uproar of Niagara—a pause or hush on the threshold of a great sensation; and this, too, in spite of the reverent attention I was mindful to bestow on the first-seen, in my experience, of the great lakes. It has the merit, from the shore, of producing a slight perplexity of vision. It is the sea, and yet just not the sea. The huge expanse, the landless line of the horizon, suggest the ocean; while an indefinable shortness of pulse, a kind of freshwater gentleness of tone, seem to contradict the idea. What meets the eye is on the ocean scale, but you feel somehow that the lake is a thing of smaller spirit. Lake navigation, therefore, seems to me not especially entertaining. The scene tends to offer, as one may say, a sort of marine-effect manqué. It has the blankness and vacancy of the sea without that vast essential swell which, amid the belting brine, so often saves the situation to the eye. I was occupied, as we crossed, in wondering whether this dull reduction of the ocean contained that which could properly be termed “scenery.” At the mouth of the Niagara River, however, after a three hours’ sail, scenery really begins, and very soon crowds upon you in force. The steamer puts into the narrow channel of the stream, and heads upward between high embankments. From this point, I think, you really enter into relations with Niagara. Little by little the elements become a picture, rich with the shadows of coming events. You have a foretaste of the great spectacle of color which you enjoy at the Falls. The even cliffs of red-brown earth are now crusted, now spotted, with autumnal orange and crimson, and laden with this ardent boskage plunge sheer into the deep-dyed green of the river. As you proceed, the river begins to tell its tale—at first in broken syllables of foam and flurry, and then, as it were, in rushing, flashing sentences and passionate interjections. Onwards from Lewiston, where you are transferred from the boat to the train, you see it from the cope of the American cliff, far beneath you, now superbly unnavigable. You have a lively sense of something happening ahead; the river, as a man near me said, has evidently been in a row. The cliffs here are immense; they form genuine vomitoria worthy of the living floods whose exit they protect. This is the first act of the drama of Niagara; for it is, I believe, one of the commonplaces of description that you instinctively harmonize and dramatize it. At the station pertaining to the railway suspension-bridge, you see in mid-air beyond an interval of murky confusion produced by the further bridge, the smoke of the trains, and the thickened atmosphere of the peopled bank, a huge far-flashing sheet which glares through the distance as a monstrous absorbent and irradiant of light. And here, in the interest of the picturesque, let me note that this obstructive bridge tends in a way to enhance the first glimpse of the cataract. Its long black span, falling dead along the shining brow of the Falls, seems shivered and smitten by their fierce effulgence, and trembles across the field of vision like some mighty mote in an excess of light. A moment later, as the train proceeds, you plunge into the village, and the cataract, save as a vague ground-tone to this trivial interlude, is, like so many other goals of aesthetic pilgrimage, temporarily postponed to the hotel.

With this postponement comes, I think, an immediate decline of expectation; for there is every appearance that the spectacle you have come so far to see is to be choked in the horribly vulgar shops and booths and catchpenny artifices which have pushed and elbowed to within the very spray of the Falls, and ply their importunities in shrill competition with its thunder. You see a multitude of hotels and taverns and shops, glaring with white paint, bedizened with placards and advertisements, and decorated by groups of those gentlemen who flourish most rankly on the soil of New York and in the vicinage of hotels; who carry their hands in their pockets, wear their hats always and every way, and, although of a sedentary habit, yet spurn the earth with their heels. A side-glimpse of the Falls, however, calls out one’s philosophy; you reflect that this is but such a sordid foreground as Turner liked to use; you hurry to where the roar grows louder, and, I was going to say, you escape from the village. In fact, however, you don’t escape from it; it is constantly at your elbow, just to the right or the left of the line of contemplation. It would be paying Niagara a poor compliment to say that, practically, she does not hurl off this chaffering by-play from her cope; but as you value the integrity of your impression, you are bound to affirm that it hereby suffers appreciable abatement. You wonder, as you stroll about, whether it is altogether an unrighteous dream that with the slow progress of culture, and the possible or impossible growth of some larger comprehension of beauty and fitness, the public conscience may not tend to ensure to such sovereign phases of nature something of the inviolability and privacy which we are slow to bestow, indeed, upon fame, but which we do not grudge at least to art. We place a great picture, a great statue, in a museum; we erect a great monument in the centre of our largest square, and if we can suppose ourselves nowadays building a cathedral, we should certainly isolate it as much as possible and subject it to no ignoble contact.

1 comment