On viewing one of these isolated masses, at first one is inclined to believe that it has been suddenly pushed up in a semi-fluid state. At St. Helena, however, I ascertained that some pinnacles, of a nearly similar figure and constitution, had been formed by the injection of melted rock into yielding strata, which thus had formed the moulds for these gigantic obelisks. The whole island is covered with wood; but from the dryness of the climate there is no appearance of luxuriance. Half-way up the mountain some great masses of the columnar rock, shaded by laurel-like trees, and ornamented by others covered with fine pink flowers but without a single leaf, gave a pleasing effect to the nearer parts of the scenery.

BAHIA, OR SAN SALVADOR. BRAZIL, Feb. 29th.—The day has past delightfully. Delight itself, however, is a weak term to express the feelings of a naturalist who, for the first time, has wandered by himself in a Brazilian forest. The elegance of the grasses, the novelty of the parasitical plants, the beauty of the flowers, the glossy green of the foliage, but above all the general luxuriance of the vegetation, filled me with admiration. A most paradoxical mixture of sound and silence pervades the shady parts of the wood. The noise from the insects is so loud, that it may be heard even in a vessel anchored several hundred yards from the shore; yet within the recesses of the forest a universal silence appears to reign. To a person fond of natural

11

history, such a day as this brings with it a deeper pleasure than he can ever hope to experience again. After wandering about for some hours, I returned to the landing-place; but, before reaching it, I was overtaken by a tropical storm. I tried to find shelter under a tree, which was so thick that it would never have been penetrated by common English rain; but here, in a couple of minutes, a little torrent flowed down the trunk. It is to this violence of the rain that we must attribute the verdure at the bottom of the thickest woods: if the showers were like those of a colder clime, the greater part would be absorbed or evaporated before it reached the ground. I will not at present attempt to describe the gaudy scenery of this noble bay, because, in our homeward voyage, we called here a second time, and I shall then have occasion to remark on it.

Along the whole coast of Brazil, for a length of at least 2000 miles, and certainly for a considerable space inland, wherever solid rock occurs, it belongs to a granitic formation. The circumstance of this enormous area being constituted of materials which most geologists believe to have been crystallised when heated under pressure, gives rise to many curious reflections. Was this effect produced beneath the depths of a profound ocean? or did a covering of strata formerly extend over it, which has since been removed? Can we believe that any power, acting for a time short of infinity, could have denuded the granite over so many thousand square leagues?

On a point not far from the city, where a rivulet entered the sea, I observed a fact connected with a subject discussed by Humboldt.1 At the cataracts of the great rivers Orinoco, Nile, and Congo, the syenitic rocks are coated by a black substance, appearing as if they had been polished with plumbago. The layer is of extreme thinness; and on analysis by Berzelius it was found to consist of the oxides of manganese and iron. In the Orinoco it occurs on the rocks periodically washed by the floods, and in those parts alone where the stream is rapid; or, as the Indians say, "the rocks are black where the waters are white." Here the coating is of a rich brown instead of a black colour, and seems to be composed of ferruginous matter alone. Hand specimens fail to give a just idea of these brown burnished stones which glitter in the sun's rays. They occur only within

12

the limits of the tidal waves; and as the rivulet slowly trickles down, the surf must supply the polishing power of the cataracts in the great rivers. In like manner, the rise and fall of the tide probably answer to the periodical inundations; and thus the same effects are produced under apparently different but really similar circumstances. The origin, however, of these coatings of metallic oxides, which seem as if cemented to the rocks, is not understood; and no reason, I believe, can be assigned for their thickness remaining the same.

1. Personal Narrative, vol. v, pt. i, p. 18.

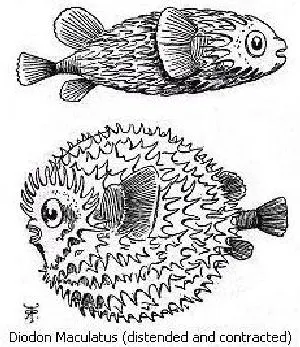

One day I was amused by watching the habits of the Diodon antennatus, which was caught swimming near the shore. This fish, with its flabby skin, is well known to possess the singular power of distending itself into a nearly spherical form. After having been taken out of water for a short time, and then again immersed in it, a considerable quantity both of water and air is absorbed by the mouth, and perhaps likewise by the branchial orifices.

1 comment