Opening on 9 April 1917, a force of British, ANZACs and Canadians managed to regain the ridge. Despite the successes at Vimy Ridge, elsewhere the Germans counter-attacked and the familiar pattern reasserted itself.

A week later, on 16 April, Nivelle launched his main offensive on which he had staked his reputation. The Second Battle of the Aisne was doomed for failure from the start. Nivelle’s carefully laid plans had fallen into German hands who prepared accordingly. The introduction of French tanks had no effect, and French artillery fell on their own infantry. The losses were huge. Nivelle’s promise of a forty-eight hour victory evaporated as the battle continued on for two weeks and petered out in early May. Nivelle, briefly the would-be saviour of France, was sacked and replaced by his former boss, Philippe Pétain, a man who was unusually sympathetic to the plight of his men. It was just as well because within the army were the first murmurs of dissent.

From dissent came mutiny. In May 1917, French soldiers refused to fight anymore. The word spread and thousands deserted. Fortunately for Pétain, his front-line troops remained in place. Behind the lines, men, worn down by war, filthy conditions, and the lack of sufficient medical care, refused to obey orders or return to the front. Painstakingly, Pétain managed to restore order through a combination of the carrot and stick. Ringleaders were arrested, court-marshalled and, in forty-three cases, executed. In the longer term, Pétain doubled a soldier’s length of leave, improved conditions, food and welfare. Most importantly, Pétain promised the French soldier that there would be no more pointless offensives or risks taken, until both the Americans had arrived and tanks were in full supply.

Air and Sea

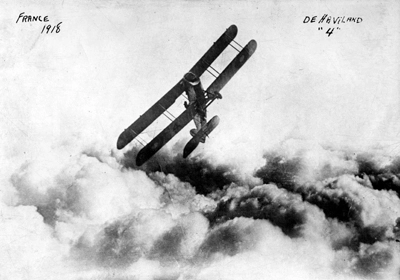

Aircraft developed substantially during the war. They were initially used for observation and reconnaissance, until the French became the first to attach a machine gun to a plane. It was a Dutchman, working for the Germans, Anton Fokker, who provided the solution for firing a machine gun through a propeller. With the development of the fighter plane came the concept of dogfights, and ‘aces’ on all sides achieved celebrity status for their acts of daring, the most renowned being the German, Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. Richthofen, credited with a record eighty kills, was shot down and killed in April 1918.

Bi-plane over France, 1918.

Bomber planes caused damage to major cities such as London, Paris and Cologne. Paris, for example, suffered 266 deaths throughout the war from aerial bombardment, be it aeroplane or zeppelin. In Britain the Royal Flying Corps was an adjunct to both the army and navy, but on 1 April 1918, in recognition of the growing importance of aerial combat, the Royal Air Force was founded.

Damaged German ship after the Battle of Jutland, 1916

On 31 May 1916, the largest sea battle took place – the Battle of Jutland. Chief Admiral of the German High Seas Fleet, Reinhard Scheer, knew full well that Britain boasted the strongest navy, but believed he could lure individual ships into battle and deal with the British fleet one vessel at a time. His grandiose plans however went awry when Britain deciphered the enemy’s communications, discovering exactly what Scheer had in mind. The battle around the Danish waters of Jutland, led by Scheer and his British counterpart, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, proved a cat and mouse affair with no clear victor, although by sheer numbers of ships sunk, the Germans claimed the honours. The clashes of big ships however came to an end. German strategy changed to greater reliance on the submarine. In January 1917, the Germans issued a proclamation that her U-boats would, from thenceforth, attack anything in sight on the east side of the Atlantic, without warning, whether neutral or not. Their idea was to prevent food and supplies reaching Britain.

1 comment