Greece eventually joined the war on the side of the Allies in July 1917.

The Ottoman Empire

In November 1914, the British sent a force to protect the Suez Canal in Egypt from Turkish troops based in Turkish-controlled Palestine. In late-January and February 1915, as expected, the Turks tried to seize the canal and again in July 1916, but both assaults were easily repulsed.

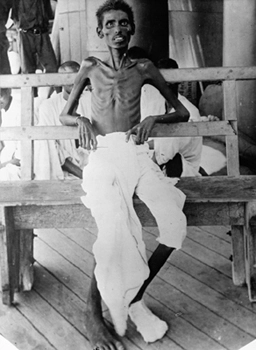

Another British force, consisting mainly of Indian troops, occupied Basra in Turkish-Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) in November 1914 to secure its oil wells. From there, with a hold on Turkish territory, it made sense to extend its gains and capture Baghdad, which would, according to Asquith, ‘maintain the authority of our flag in the East’. In August 1915, a force led by General Charles Townsend pushed forward under 43° C heat and, along the way, occupied the town of Kut-el-Amara. Urged to advance onto Baghdad, Townsend did but, meeting a determined Turkish counter-attack, was forced back to Kut where his men came under siege. With supplies running low and the situation desperate, attempts were made to rescue Townsend but these failed, with a loss of 23,000 lives. After 147 days of siege, starving and unable to hold out, Townsend surrendered on 29 April 1916. His 13,000 men, one third of whom were Indian, were marched off to captivity, where up to 70 per cent were to die of malnutrition.

Indian soldier shortly after the Siege of Kut, 1916

In December 1916, the British, under General Stanley Maude, made a fresh attempt to capture Baghdad. Maude recaptured Kut and on 11 March 1917, beat the Turks out of Baghdad. ‘Our armies,’ proclaimed Maude to the citizens of Baghdad, ‘do not come into your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators.’

In January 1917, British troops marched towards Jerusalem, determined to oust Turkey from Palestine. Along the way, the British tried twice to take Gaza and twice failed. The third attempt, in November, led by General Sir Edmund Allenby, was successful, leading to the capture of Jerusalem on 11 December 1917. In January 1916, in a secret agreement known as the Sykes–Picot Agreement (after its authors), the British and French agreed the partition of Palestine and Mesopotamia, at that point still under the rule of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. At the same time, the British were offering bits of Turkey to the Russians, Italians, and the Arabs. The Arabs, accordingly, played their part in the British campaign. Led by the enigmatic T. E. Lawrence, they continuously disrupted Turkish communications through sabotage and guerrilla tactics. On realizing the British had conflicting plans for Palestine, the Arabs felt betrayed, even more so with the Balfour Declaration of November 1917. Britain’s foreign secretary, Arthur Balfour, proposed a permanent settlement for Jews within Palestine. The stipulation that ‘nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine’ did nothing to allay Arab concerns.

Verdun

In Germany, Falkenhayn decided that Germany’s ‘arch enemy’ was not France, but Britain. But to destroy Britain’s will, Germany had first to defeat France. In a ‘Christmas memorandum’ to the Kaiser, Falkenhayn proposed an offensive that would compel the French to ‘throw in every man they have. If they do so,’ he continued, ‘the forces of France will bleed to death’. The place to do this, Falkenhayn declared, would be Verdun.

An ancient town, Verdun was surrounded by a string of sixty interlocked and reinforced forts. On 21 February 1916, 1,200 German guns lined over only eight miles pounded the city which, despite intelligence warning of the impending attack, remained poorly defended. Verdun, symbolically significant to the French, was deemed not so important by the upper echelon of France’s military. Joffre was slow to respond until the exasperated French prime minister, Aristide Briand, paid a night-time visit to Joffre, waking him from his slumber and insisting that he take the situation more seriously: ‘You may not think losing Verdun a defeat but everyone else will.’

Sent by Joffre, Henri-Philippe Pétain organized a stern defence of the city and managed to protect the only road open to the French. Every day, while under continuous fire, 2,000 lorries made a return trip along the 45-mile Voie Sacrée (‘Sacred Way’) bringing in vital supplies and reinforcements to be fed into the furnace that had become Verdun. Serving under Pétain was General Robert Nivelle who famously promised that ‘on ne passe pas’ (they shall not pass), a quote often attributed to Pétain.

1 comment