It was clear to me that she had had similar trouble with passages that troubled me. I had been ready to use (and duly acknowledge) any felicitous solutions of hers, but as it turned out, her words regularly drove me to press on and find new solutions of my own.

The first and perhaps greatest problem is the very title of the book. In Italian, “coscienza” means both “conscience” and “consciousness,” and the word recurs often in the body of the novel. De Zoete’s choice of “confessions,” skirting the original word deftly, was inspired but, I felt, finally misleading, placing Zeno Cosini in a line descended from Augustine and Rousseau. (To one of my Catholic background, the word also had a religious, sacramental connotation that I felt was unsuitable.) Then, one day, in an article in The Times Literary Supplement, I read that in the past, the English word “conscience” had also had the meaning of “consciousness.” The article quoted Shakespeare (“conscience doth make cowards of us all”). And I decided that my title would be Zeno’s Conscience.

Translation is often described as a lonely profession. I have never found it so. True, during most of the work, I am alone in my study, facing the blank screen and the printed page. But I also have the pleasure of discussing work and words with others, with colleagues and friends. I began this translation years ago in Italy and completed it at Bard College, where the campus teems with Svevians, always ready to talk about his great novel. At Bard, I must thank my valued colleagues James Ghace, Frederick Hammond, Robert Kelly, William Mullen, Maria Assunta Nicoletti, and Carlo Zei. I am also grateful to my student Jorge Santana for his help, and to my former student Kristina Olson for collaborating on the bibliographical note. In New York, my old friend Riccardo Gori Montanelli (who helped me with some of my first translations, in Charlottesville, Virginia, fifty years ago) came to my assistance with some stock-market terminology, and my editor, LuAnn Walther, and her assistant, John Siciliano, helped with the final stages of the long process of seeing Zeno’s Conscience into print.

William Weaver

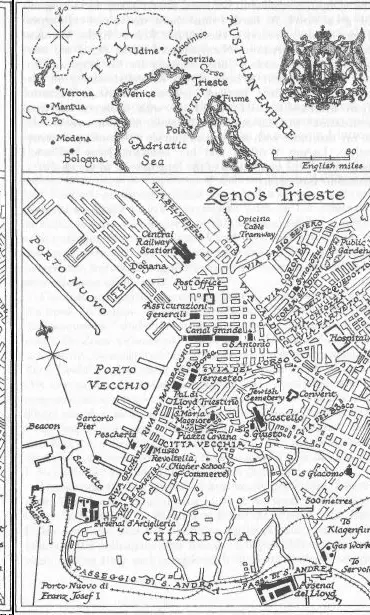

MAP OF ZENO’S TRIESTE

PREFACE

I am the doctor occasionally mentioned in this story, in unflattering terms. Anyone familiar with psychoanalysis knows how to assess the patient’s obvious hostility toward me.

I will not discuss psychoanalysis here, because in the following pages it is discussed more than enough. I must apologize for having suggested my patient write his autobiography; students of psychoanalysis will frown on this new departure. But he was an old man, and I hoped that recalling his past would rejuvenate him, and that the autobiography would serve as a useful prelude to his analysis. Even today my idea still seems a good one to me, for it achieved results far beyond my hopes. The results would have been even greater if the patient had not suspended treatment just when things were going well, denying me the fruit of my long and painstaking analysis of these memories.

I am publishing them in revenge, and I hope he is displeased. I want him to know, however, that I am prepared to share with him the lavish profits I expect to make from this publication, on condition that he resume his treatment. He seemed so curious about himself! If he only knew the countless surprises he might enjoy from discussing the many truths and the many lies he has assembled here!…

Doctor S.

PREAMBLE

review my childhood? More than a half-century stretches between that time and me, but my farsighted eyes could perhaps perceive it if the light still glowing there were not blocked by obstacles of every sort, outright mountain peaks: all my years and some of my hours.

The doctor has urged me not to insist stubbornly on trying to see all that far back. Recent things can also be valuable, and especially fantasies and last night’s dreams. But there should be at least some kind of order, and to help me begin ab ovo, the moment I left the doctor, who is going out of town shortly and will be absent from Trieste for some time, I bought and read a treatise on psychoanalysis, just to make his task easier. It’s not hard to understand, but it’s very boring.

Now, having dined, comfortably lying in my overstuffed lounge chair, I am holding a pencil and a piece of paper. My brow is unfurrowed because I have dismissed all concern from my mind. My thinking seems something separate from me. I can see it. It rises and falls… but that is its only activity. To remind it that it is my thinking and that its duty is to make itself evident, I grasp the pencil. Now my brow does wrinkle, because each word is made up of so many letters and the imperious present looms up and blots out the past.

Yesterday I tried to achieve maximum relaxation. The experiment ended in deepest sleep, and its only effect on me was a great repose and the curious sensation of having seen, during that sleep, something important.

1 comment