In this time they had got some remote Acquaintance with a Victualling-House at the out-skirts of the Town, to whom they called at a Distance to bring some little Things that they wanted, and which they caus’d to be set down at a Distance, and always paid for very honestly.

During this Time, the younger People of the Town came frequently pretty near them, and wou’d stand and look at them, and sometimes talk with them at some Space between; and particularly it was observed, that the first Sabbath Day the poor People kept retir’d, worship’d God together, and were heard to sing Psalms.

These Things and a quiet inoffensive Behaviour, began to get them the good Opinion of the Country, and People began to pity them and speak very well of them; the Consequence of which was, that upon the occasion of a very wet rainy Night, a certain Gentleman who liv’d in the Neighbourhood, sent them a little Cart with twelve Trusses or Bundles of Straw, as well for them to lodge upon, as to cover and thatch their Huts, and to keep them dry: The Minister of a Parish not far off, not knowing of the other, sent them also about two Bushels of Wheat, and half a Bushel of white Peas.

They were very thankful to-be-sure for this Relief, and particularly the Straw was a very great Comfort to them; for tho’ the ingenious Carpenter had made Frames for them to lie in like Troughs, and fill’d them with Leaves of Trees, and such Things as they could get, and had cut all their Tent-cloth out to make them Coverlids, yet they lay damp, and hard, and unwholesome till this Straw came, which was to them like Feather-beds, and, as John said, more welcome than Featherbeds wou’d ha’ been at another time.

This Gentleman and the Minister having thus begun and given an Example of Charity to these Wanderers, others quickly followed, and they receiv’d every Day some Benevolence or other from the People, but chiefly from the Gentlemen who dwelt in the Country round about; some sent them Chairs, Stools, Tables, and such Houshold Things as they gave Notice they wanted; some sent them Blankets, Rugs and Coverlids; some Earthen-ware; and some Kitchin-ware for ordering their Food.

Encourag’d by this good Usage, their Carpenter in a few Days, built them a large Shed or House with Rafters, and a Roof in Form, and an upper Floor in which they lodged warm, for the Weather began to be damp and cold in the beginning of September; But this House being very well Thatch’d, and the Sides and Roof made very thick, kept out the Cold well enough: He made also an earthen Wall at one End, with a Chimney in it; and another of the Company, with a vast deal of Trouble and Pains, made a Funnel to the Chimney to carry out the Smoak.

Here they liv’d very comfortably, tho’ coarsely, till the beginning of September, when they had the bad News to hear, whether true or not, that the Plague, which was very hot at Waltham-Abby on one side, and at Rumford and Brent-Wood on the other side; was also come to Epping, to Woodford, and to most of the Towns upon the Forest, and which, as they said, was brought down among them chiefly by the Higlers* and such People as went to and from London with Provisions.

If this was true, it was an evident Contradiction to that Report which was afterwards spread all over England, but which, as I have said, I cannot confirm of my own Knowledge, namely, That the Market People carrying Provisions to the City, never got the Infection or carry’d it back into the Country; both which I have been assured, has been false.

It might be that they were preserv’d even beyond Expectation, though not to a Miracle, that abundance went and come, and were not touch’d, and that was much for the Encouragement of the poor People of London, who had been compleatly miserable, if the People that brought Provisions to the Markets had not been many times wonderfully preserv’d, or at least more preserv’d than cou’d be reasonably expected.

But now these new Inmates began to be disturb’d more effectually, for the Towns about them were really infected, and they began to be afraid to trust one another so much as to go abroad for such things as they wanted, and this pinch’d them very hard; for now they had little or nothing but what the charitable Gentlemen of the Country supply’d them with: But for their Encouragement it happen’d, that other Gentlemen in the Country who had not sent ’em any thing before, began to hear of them and supply them, and one sent them a large Pig, that is to say a Porker; another two Sheep; and another sent them a Calf: In short, they had Meat enough, and, sometimes had Cheese and Milk, and all such things; They were chiefly put to it for Bread, for when the Gentlemen sent them Corn they had no where to bake it, or to grind it: This made them eat the first two Bushel of Wheat that was sent them in parched Corn, as the Israelites of old did without grinding or making Bread of it.*

At last they found means to carry their Corn to a Windmill near Woodford, where they had it ground; and afterwards the Biscuit Baker made a Hearth so hollow and dry that he cou’d bake Biscuit Cakes tolerably well; and thus they came into a Condition to live without any assistance or supplies from the Towns; and it was well they did, for the Country was soon after fully Infected, and about 120 were said to have died of the Distemper in the Villages near them, which was a terrible thing to them.

On this they call’d a new Council, and now the Towns had no need to be afraid they should settle near them, but on the contrary several Families of the poorer sort of the Inhabitants quitted their Houses, and built Hutts in the Forest after the same manner as they had done: But it was observ’d, that several of these poor People that had so remov’d, had the Sickness even in their Hutts or Booths; the Reason of which was plain, namely, not because they removed into the Air, but because they did not remove time enough, that is to say, not till by openly conversing with the other People their Neighbours, they had the Distemper upon them, or, (as may be said) among them, and so carry’d it about them whither they went: Or, (2.) Because they were not careful enough after they were safely removed out of the Towns, not to come in again and mingle with the diseased People.

But be it which of these it will, when our Travellers began to perceive that the Plague was not only in the Towns, but even in the Tents and Huts on the Forest near them, they began then not only to be afraid, but to think of decamping and removing; for had they stay’d, they wou’d ha’ been in manifest Danger of their Lives.

It is not to be wondered that they were greatly afflicted, as being obliged to quit the Place where they had been so kindly receiv’d, and where they had been treated with so much Humanity and Charity; but Necessity, and the hazard of Life, which they came out so far to preserve, prevail’d with them, and they saw no Remedy. John however thought of a Remedy for their present Misfortune, namely, that he would first acquaint that Gentleman who was their principal Benefactor, with the Distress they were in, and to crave his Assistance and Advice.

The good charitable Gentleman encourag’d them to quit the Place, for fear they should be cut off from any Retreat at all, by the Violence of the Distemper; but whither they should go, that he found very hard to direct them to. At last John ask’d of him, whether he (being a Justice of the Peace) would give them Certificates of Health to other Justices who they might come before, that so whatever might be their Lot they might not be repulsed now they had been also so long from London. This his Worship immediately granted, and gave them proper Letters of Health, and from thence they were at Liberty to travel whither they pleased.

Accordingly they had a full Certificate of Health, intimating, That they had resided in a Village in the County of Essex so long, that being examined and scrutiniz’d sufficiently, and having been retir’d from all Conversation for above 40 Days, without any appearance of Sickness, they were therefore certainly concluded to be Sound Men, and might be safely entertain’d any where, having at last remov’d rather for fear of the Plague, which was come into such a Town, rather than for having any signal of Infection upon them, or upon any belonging to them.

With this Certificate they remov’d, tho’ with great Reluctance; and John inclining not to go far from Home, they mov’d towards the Marshes on the side of Waltham: But here they found a Man, who it seems kept a Weer or Stop upon the River, made to raise the Water for the Barges which go up and down the River, and he Terrified them with dismal Stories of the Sickness having been spread into all the Towns on the River, and near the River, on the side of Middlesex and Hertfordshire; that is to say, into Waltham, Waltham-Cross, Enfield and Ware, and all the Towns on the Road, that they were afraid to go that way; tho’ it seems the Man impos’d upon them, for that the thing was not really true.

However it Terrified them, and they resolved to move cross the Forest towards Rumford and Brent-Wood; but they heard that there were numbers of People fled out of London that way, who lay up and down in the Forest call’d Henalt Forest, reaching near Rumford, and who having no Subsistence of Habitation, not only liv’d oddly, and suffered great Extremities in the Woods and Fields for want of Relief, but were said to be made so desperate by those Extremities, as that they offer’d many Violences to the County, robb’d and plunder’d, and kill’d Cattle, and the like; that others building Hutts and Hovels by the Road-side Begg’d, and that with an Importunity next Door to demanding Relief; so that the County was very uneasy, and had been oblig’d to take some of them up.

This, in the first Place intimated to them, that they would be sure to find the Charity and Kindness of the County, which they had found here where they were before, hardned and shut up against them; and that on the other Hand, they would be question’d where-ever they came, and would be in Danger of Violence from others in like Cases as themselves.

Upon all these Considerations, John, their Captain, in all their Names, went back to their good Friend and Benefactor, who had reliev’d them before, and laying their Case truly before him, humbly ask’d his Advice; and he as kindly advised them to take up their old Quarters again, or if not, to remove but a little further out of the Road, and directed them to a proper Place for them; and as they really wanted some House rather than Huts to shelter them at that time of the Year, it growing on towards Michaelmas, they found an old decay’d House, which had been formerly some Cottage or little Habitation, but was so out of repair as scarce habitable, and by the consent of a Farmer to whose Farm it belong’d, they got leave to make what use of it they could.

The ingenious Joyner and all the rest by his Directions, went to work with it, and in a very few Days made it capable to shelter them all in case of bad Weather, and in which there was an old Chimney, and an old Oven, tho’ both lying in Ruins, yet they made them both fit for Use, and raising Additions, Sheds, and Leantoo’s on every side, they soon made the House capable to hold them all.

They chiefly wanted Boards to make Window-shutters, Floors, Doors, and several other Things; but as the Gentlemen above favour’d them, and the Country was by that Means made easy with them, and above all, that they were known to be all sound and in good health, every Body help’d them with what they could spare.

Here they encamp’d for good and all, and resolv’d to remove no more; they saw plainly how terribly alarm’d that County was every where, at any Body that came from London; and that they should have no admittance any where but with the utmost Difficulty, at least no friendly Reception and Assistance as they had receiv’d here.

Now altho’ they receiv’d great Assistance and Encouragement from the Country Gentlemen and from the People round about them, yet they were put to great Straits, for the Weather grew cold and wet in October and November, and they had not been us’d to so much hardship; so that they got Colds in their Limbs, and Distempers, but never had the Infection: And thus about December they came home to the City again.

I give this Story thus at large, principally to give an Account what became of the great Numbers of People which immediately appear’d in the City as soon as the Sickness abated: For, as I have said, great Numbers of those that were able and had Retreats in the Country, fled to those Retreats; So when it was encreased to such a frightful Extremity as I have related, the midling People who had not Friends, fled to all Parts of the Country where they cou’d get shelter, as well those that had Money to relieve themselves; as those that had not. Those that had Mony always fled farthest, because they were able to subsist themselves; but those who were empty, suffer’d, as I have said, great Hardships, and were often driven by Necessity to relieve their Wants at the Expence of the Country: By that Means the Country was made very uneasie at them, and sometimes took them up, tho’ even then they scarce knew what to do with them, and were always very backward to punish them, but often too they forced them from Place to Place, till they were oblig’d to come back again to London.

I have, since my knowing this Story of John and his Brother, enquir’d and found, that there were a great many of the poor disconsolate People, as above, fled into the Country every way, and some of them got little Sheds, and Barns, and Out-houses to live in, where they cou’d obtain so much Kindness of the Country, and especially where they had any the least satisfactory Account to give of themselves, and particularly that they did not come out of London too late. But others, and that in great Numbers, built themselves little Hutts and Retreats in the Fields and Woods, and liv’d like Hermits in Holes and Caves, or any Place they cou’d find; and where, we may be sure, they suffer’d great Extremities, such that many of them were oblig’d to come back again whatever the Danger was; and so those little Huts were often found empty, and the Country People suppos’d the Inhabitants lay Dead in them of the Plague, and would not go near them for fear, no not in a great while; nor is it unlikely but that some of the unhappy Wanderers might die so all alone, even sometimes for want of Help, as particularly in one Tent or Hutt, was found a Man dead, and on the Gate of a Field just by, was cut with his Knife in uneven Letters, the following Words, by which it may be suppos’d the other Man escap’d, or that one dying first, the other bury’d him as well as he could;

O mIsErY!

We BoTH ShaLL DyE,

WoE, WoE.

I have given an Account already of what I found to ha’ been the Case down the River among the Sea-faring Men, how the Ships lay in the Offing, as ’tis call’d, in Rows or Lines a-stern of one another, quite down from the Pool as far as I could see. I have been told, that they lay in the same manner quite down the River as low as Gravesend, and some far beyond, even every where, or in every Place where they cou’d ride with Safety as to Wind and Weather; Nor did I ever hear that the Plague reach’d to any of the People on board those Ships, except such as lay up in the Pool, or as high as Deptford Reach, altho’ the People went frequently on Shoar to the Country Towns and Villages, and Farmers Houses, to buy fresh Provisions, Fowls, Pigs, Calves, and the like for their Supply.

Likewise I found that the Watermen on the River above the Bridge, found means to convey themselves away up the River as far as they cou’d go; and that they had, many of them, their whole Families in their Boats, cover’d with Tilts and Bales,* as they call them, and furnish’d with Straw within for their Lodging; and that they lay thus all along by the Shoar in the Marshes, some of them setting up little Tents with their Sails, and so lying under them on Shoar in the Day, and going into their Boats at Night; and in this manner, as I have heard, the River-sides were lin’d with Boats and People as long as they had any thing to subsist on, or cou’d get any thing of the Country; and indeed the Country People, as well Gentlemen as others, on these and all other Occasions, were very forward to relieve them, but they were by no means willing to receive them into their Towns and Houses, and for that we cannot blame them.

There was one unhappy Citizen, within my Knowledge, who had been Visited in a dreadful manner, so that his Wife and all his Children were Dead, and himself and two Servants only left, with an elderly Woman a near Relation, who had nurs’d those that were dead as well as she could: This disconsolate Man goes to a Village near the Town, tho’ not within the Bills of Mortality, and finding an empty House there, enquires out the Owner, and took the House: After a few Days he got a Cart and loaded it with Goods, and carries them down to the House; the People of the Village oppos’d his driving the Cart along, but with some Arguings, and some Force, the Men that drove the Cart along, got through the Street up to the Door of the House, there the Constable resisted him again, and would not let them be brought in. The Man caus’d the Goods to be unloaden and lay’d at the Door, and sent the Cart away; upon which they carry’d the Man before a Justice of Peace; that is to say, they commanded him to go, which he did. The Justice order’d him to cause the Cart to fetch away the Goods again, which he refused to do; upon which the Justice order’d the Constable to pursue the Carters and fetch them back, and make them re-load the Goods and carry them away, or to set them in the Stocks till they came for farther Orders; and if they could not find them, nor the Man would not consent to take them away, they should cause them to be drawn with Hooks from the House-Door and burnt in the Street. The poor distress’d Man upon this fetch’d the Goods again, but with grievous Cries and Lamentations at the hardship of his Case. But there was no Remedy; Self-preservation oblig’d the People to those Severities, which they wou’d not otherwise have been concern’d in: Whether this poor Man liv’d or dy’d I cannot tell, but it was reported that he had the Plague upon him at that time; and perhaps the People might report that to justify their Usage of him; but it was not unlikely, that either he or his Goods, or both, were dangerous, when his whole Family had been dead of the Distemper so little a while before.

I kno’ that the Inhabitants of the Towns adjacent to London, were much blamed for Cruelty to the poor People that ran from the Contagion in their Distress; and many very severe things were done, as may be seen from what has been said; but I cannot but say also that where there was room for Charity and Assistance to the People, without apparent Danger to themselves, they were willing enough to help and relieve them. But as every Town were indeed Judges in their own Case, so the poor People who ran abroad in their Extremities, were often ill-used and driven back again into the Town; and this caused infinite Exclamations and Out-cries against the Country Towns, and made the Clamour very popular.

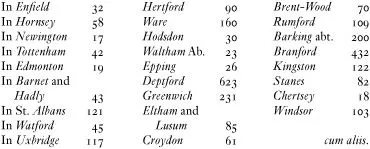

And yet more or less, maugre all their Caution, there was not a Town of any Note within ten (or I believe twenty) Miles of the City, but what was more or less Infected, and had some died among them. I have heard the Accounts of several; such as they were reckon’d up as follows.

Another thing might render the Country more strict with respect to the Citizens, and especially with respect to the Poor; and this was what I hinted at before, namely, that there was a seeming propensity, or a wicked Inclination in those that were Infected to infect others.

There have been great Debates among our Physicians, as to the Reason of this; some will have it to be in the Nature of the Disease, and that it impresses every one that is seized upon by it, with a kind of a Rage, and a hatred against their own Kind, as if there was a malignity, not only in the Distemper to communicate it self, but in the very Nature of Man, prompting him with evil Will, or an evil Eye, that as they say in the Case of a mad Dog, who tho’ the gentlest Creature before of any of his Kind, yet then will fly upon and bite any one that comes next him and those as soon as any, who had been most observ’d by him before.

Others plac’d it to the Account of the Coruption of humane Nature, which cannot bear to see itself more miserable than others of its own Species, and has a kind of involuntary Wish, that all Men were as unhappy, or in as bad a Condition as itself.

Others say, it was only a kind of Desperation, not knowing or regarding what they did, and consequently unconcern’d at the Danger or Safety, not only of any Body near them, but even of themselves also: And indeed when Men are once come to a Condition to abandon themselves, and be unconcern’d for the Safety, or at the Danger of themselves, it cannot be so much wondered that they should be careless of the Safety of other People.

But I choose to give this grave Debate a quite different turn, and answer it or resolve it all by saying, That I do not grant the Fact. On the contrary, I say, that the Thing is not really so, but that it was a general Complaint rais’d by the People inhabiting the out-lying Villages against the Citizens, to justify, or at least excuse those Hardships and Severities so much talk’d of, and in which Complaints, both Sides may be said to have injur’d one another; that is to say, the Citizens pressing to be received and harbour’d in time of Distress, and with the Plague upon them, complain of the Cruelty and Injustice of the Country People, in being refused Entrance, and forc’d back again with their Goods and Families; and the Inhabitants finding themselves so imposed upon, and the Citizens breaking in as it were upon them whether they would or no, complain, that when they were infected, they were not only regardless of others, but even willing to infect them; neither of which were really true, that is to say, in the Colours they were describ’d in.

It is true, there is something to be said for the frequent Alarms which were given to the Country, of the resolution of the People in London to come out by Force, not only for Relief, but to Plunder and Rob, that they ran about the Streets with the Distemper upon them without any control; and that no Care was taken to shut up Houses, and confine the sick People from infecting others; whereas, to do the Londoners Justice, they never practised such things, except in such particular Cases as I have mention’d above, and such-like. On the other Hand every thing was managed with so much Care, and such excellent Order was observ’d in the whole City and Suburbs, by the Care of the Lord Mayor and Aldermen; and by the Justices of the Peace, Churchwardens, &c. in the out-Parts; that London may be a Pattern to all the Cities in the World for the good Government and the excellent Order that was every where kept, even in the time of the most violent Infection; and when the People were in the utmost Consternation and Distress. But of this I shall speak by itself.

One thing, it is to be observ’d, was owing principally to the Prudence of the Magistrates, and ought to be mention’d to their Honour, (viz.) The Moderation which they used in the great and difficult Work of shutting up of Houses: It is true, as I have mentioned, that the shutting up of Houses was a great Subject of Discontent, and I may say indeed the only Subject of Discontent among the People at that time; for the confining the Sound in the same House with the Sick, was counted very terrible, and the Complaints of People so confin’d were very grievous; they were heard into the very Streets, and they were sometimes such that called for Resentment, tho’ oftner for Compassion; they had no way to converse with any of their Friends but out at their Windows, where they wou’d make such piteous Lamentations, as often mov’d the Hearts of those they talk’d with, and of others who passing by heard their Story; and as those Complaints oftentimes reproach’d the Severity, and sometimes the Insolence of the Watchmen plac’d at their Doors, those Watchmen wou’d answer saucily enough; and perhaps be apt to affront the People who were in the Street talking to the said Families; for which, or for their ill Treatment of the Families, I think seven or eight of them in several Places were kill’d; I know not whether I shou’d say murthered or not, because I cannot enter into the particular Cases. It is true, the Watchmen were on their Duty, and acting in the Post where they were plac’d by a lawful Authority; and killing any publick legal Officer in the Execution of his Office, is always in the Language of the Law call’d Murther. But as they were not authoriz’d by the Magistrate’s Instructions, or by the Power they acted under, to be injurious or abusive, either to the People who were under their Observation, or to any that concern’d themselves for them; so when they did so, they might be said to act themselves, not their Office; to act as private Persons, not as Persons employ’d; and consequently if they brought Mischief upon themselves by such an undue Behaviour, that Mischief was upon their own Heads; and indeed they had so much the hearty Curses of the People, whether they deserv’d it or not, that whatever befel them no body pitied them, and every Body was apt to say, they deserv’d it, whatever it was; nor do I remember that any Body was ever punish’d, at least to any considerable Degree, for whatever was done to the Watchmen that guarded their Houses.

What variety of Stratagems were used to escape and get out of Houses thus shut up, by which the Watchmen were deceived or overpower’d, and that the People got away, I have taken notice of already, and shall say no more to that: But I say the Magistrates did moderate and ease Families upon many Occasions in this Case, and particularly in that of taking away, or suffering to be remov’d the sick Persons out of such Houses, when they were willing to be remov’d either to a Pest-House, or other Places, and sometimes giving the well Persons in the Family so shut up, leave to remove upon Information given that they were well, and that they would confine themselves in such Houses where they went, so long as should be requir’d of them. The Concern also of the Magistrates for the supplying such poor Families as were infected; I say, supplying them with Necessaries, as well Physick as Food, was very great, and in which they did not content themselves with giving the necessary Orders to the Officers appointed, but the Aldermen in Person, and on Horseback frequently rid to such Houses, and caus’d the People to be ask’d at their Windows, whether they were duly attended, or not? Also, whether they wanted any thing that was necessary, and if the Officers had constantly carry’d their Messages, and fetch’d them such things as they wanted, or not? And if they answered in the Affirmative, all was well; but if they complain’d, that they were ill supply’d, and that the Officer did not do his Duty, or did not treat them civilly, they (the Officers) were generally remov’d, and others plac’d in their stead.

It is true, such Complaint might be unjust, and if the Officer had such Arguments to use as would convince the Magistrate, that he was right, and that the People had injur’d him, he was continued, and they reproved. But this part could not well bear a particular Inquiry, for the Parties could very ill be brought face to face, and a Complaint could not be well heard and answer’d in the Street, from the Windows, as was the Case then; the Magistrates therefore generally chose to favour the People, and remove the Man, as what seem’d to be the least Wrong, and of the least ill Consequence; seeing, if the Watchman was injur’d yet they could readily make him amends by giving him another Post of the like Nature; but if the Family was injur’d, there was no Satisfaction could be made to them, the Damage perhaps being irreparable, as it concern’d their Lives.

A great variety of these Cases frequently happen’d between the Watchmen and the poor People shut up, besides those I formerly mention’d about escaping; sometimes the Watchmen were absent, sometimes drunk, sometimes asleep when the People wanted them, and such never fail’d to be punish’d severely, as indeed they deserv’d.

But after all that was or could be done in these Cases, the shutting up of Houses, so as to confine those that were well with those that were sick, had very great Inconveniences in it, and some that were very tragical, and which merited to have been consider’d if there had been room for it; but it was authoriz’d by a Law, it had the publick Good in view, as the End chiefly aim’d at, and all the private Injuries that were done by the putting it in Execution, must be put to the account of the publick Benefit.

It is doubtful to this day, whether in the whole it contributed any thing to the stop of the Infection, and indeed, I cannot say it did; for nothing could run with greater Fury and Rage than the Infection did when it was in its chief Violence; tho’ the Houses infected were shut up as exactly, and as effectually as it was possible. Certain it is, that if all the infected Persons were effectually shut in, no sound Person could have been infected by them, because they could not have come near them. But the Case was this, and I shall only touch it here, namely, that the Infection was propagated insensibly, and by such Persons as were not visibly infected, who neither knew who they infected, or who they were infected by.

A House in White-Chapel was shut up for the sake of one Infected Maid, who had only Spots, not the Tokens come out upon her, and recover’d; yet these People obtain’d no Liberty to stir, neither for Air or Exercise forty Days; want of Breath, Fear, Anger, Vexation, and all the other Griefs attending such an injurious Treatment, cast the Mistress of the Family into a Fever, and Visitors came into the House, and said it was the Plague, tho’ the Physicians declar’d it was not; however the Family were oblig’d to begin their Quarantine anew, on the Report of the Visitor or Examiner, tho’ their former Quarantine wanted but a few Days of being finish’d. This oppress’d them so with Anger and Grief, and, as before, straiten’d them also so much as to Room, and for want of Breathing and free Air, that most of the Family fell sick, one of one Distemper, one of another, chiefly Scorbutick Ailments; only one a violent Cholick, ’till after several prolongings of their Confinement, some or other of those that came in with the Visitors to inspect the Persons that were ill, in hopes of releasing them, brought the Distemper with them, and infected the whole House, and all or most of them died, not of the Plague, as really upon them before, but of the Plague that those People brought them, who should ha’ been careful to have protected them from it; and this was a thing which frequently happen’d, and was indeed one of the worst Consequences of shutting Houses up.

I had about this time a little Hardship put upon me, which I was at first greatly afflicted at, and very much disturb’d about; tho’ as it prov’d, it did not expose me to any Disaster; and this was being appointed by the Alderman of Portsoken Ward, one of the Examiners of the Houses in the Precinct where I liv’d; we had a large Parish, and had no less than eighteen Examiners, as the Order call’d us, the People call’d us Visitors. I endeavour’d with all my might to be excus’d from such an Employment, and used many Arguments with the Alderman’s Deputy to be excus’d; particularly I alledged, that I was against shutting up Houses at all, and that it would be very hard to oblige me, to be an Instrument in that which was against my Judgment, and which I did verily believe would not answer the End it was intended for, but all the Abatement I could get was only, that whereas the Officer was appointed by my Lord Mayor to continue two Months, I should be obliged to hold it but three Weeks, on Condition, nevertheless that I could then get some other sufficient Housekeeper to serve the rest of the Time for me, which was, in short, but a very small Favour, it being very difficult to get any Man to accept of such an Employment, that was fit to be intrusted with it.

It is true that shutting up of Houses had one Effect, which I am sensible was of Moment, namely, it confin’d the distemper’d People, who would otherwise have been both very troublesome and very dangerous in their running about Streets with the Distemper upon them, which when they were delirious, they would have done in a most frightful manner; and as indeed they began to do at first very much, ’till they were thus restrain’d; nay, so very open they were, that the Poor would go about and beg at peoples Doors, and say they had the Plague upon them, and beg Rags for their Sores, or both, or any thing that delirious Nature happen’d to think of.

A poor unhappy Gentlewoman, a substantial Citizen’s Wife was (if the Story be true) murther’d by one of these Creatures in Aldersgate-street, or that Way: He was going along the Street, raving mad to be sure, and singing, the People only said, he was drunk; but he himself said, he had the Plague upon him, which, it seems, was true; and meeting this Gentlewoman, he would kiss her; she was terribly frighted as he was only a rude Fellow, and she run from him, but the Street being very thin of People, there was no body near enough to help her: When she saw he would overtake her, she turn’d, and gave him a Thrust so forcibly, he being but weak, and push’d him down backward: But very unhappily, she being so near, he caught hold of her, and pull’d her down also; and getting up first, master’d her, and kiss’d her; and which was worst of all, when he had done, told her he had the Plague, and why should not she have it as well as he. She was frighted enough before, being also young with Child; but when she heard him say, he had the Plague, she scream’d out and fell down in a Swoon, or in a Fit, which tho’ she recover’d a little, yet kill’d her in a very few Days, and I never heard whether she had the Plague or no.

Another infected Person came, and knock’d at the Door of a Citizen’s House, where they knew him very well; the Servant let him in, and being told the Master of the House was above, he ran up, and came into the Room to them as the whole Family was at supper: They began to rise up a little surpriz’d, not knowing what the Matter was, but he bid them sit still, he only came to take his leave of them. They ask’d him, Why Mr.——where are you going? Going, says he, I have got the Sickness, and shall die to morrow Night. ’Tis easie to believe, though not to describe the Consternation they were all in, the Women and the Man’s Daughters which were but little Girls, were frighted almost to Death, and got up, one running out at one Door, and one at another, some down-Stairs and some up-Stairs, and getting together as well as they could, lock’d themselves into their Chambers, and screamed out at the Window for Help, as if they had been frighted out of their Wits: The Master more compos’d than they, tho’ both frighted and provok’d, was going to lay Hands on him, and thro’ him down Stairs, being in a Passion, but then considering a little the Condition of the Man and the Danger of touching him, Horror seiz’d his Mind, and he stood still like one astonished. The poor distemper’d Man all this while, being as well diseas’d in his Brain as in his Body, stood still like one amaz’d; at length he turns round, Ay! says he, with all the seeming calmness imaginable, Is it so with you all! Are you all disturb’d at me? why then I’ll e’en go home and die there. And so he goes immediately down Stairs: The Servant that had let him in goes down after him with a Candle, but was afraid to go past him and open the Door, so he stood on the Stairs to see what he wou’d do; the Man went and open’d the Door, and went out and flung the Door after him: It was some while before the Family recover’d the Fright, but as no ill Consequence attended, they have had occasion since to speak of it (you may be sure) with great Satisfaction.

1 comment