Tho’ the Man was gone it was some time, nay, as I heard, some Days before they recover’d themselves of the Hurry they were in, nor did they go up and down the House with any assurance, till they had burnt a great variety of Fumes and Perfumes in all the Rooms, and made a great many Smoaks of Pitch, of Gunpowder, and of Sulphur, all separately shifted; and washed their Clothes, and the like: As to the poor Man whether he liv’d or dy’d I don’t remember.

It is most certain, that if by the Shutting up of Houses the sick had not been confin’d, multitudes who in the height of their Fever were Delirious and Distracted, wou’d ha’ been continually running up and down the Streets, and even as it was, a very great number did so, and offer’d all sorts of Violence to those they met, even just as a mad Dog runs on and bites at every one he meets; nor can I doubt but that shou’d one of those infected diseased Creatures have bitten any Man or Woman, while the Frenzy of the Distemper was upon them, they, I mean the Person so wounded, wou’d as certainly ha’ been incurably infected, as one that was sick before and had the Tokens upon him.

I heard of one infected Creature, who running out of his Bed in his Shirt, in the anguish and agony of his Swellings, of which he had three upon him, got his Shoes on and went to put on his Coat, but the Nurse resisting and snatching the Coat from him, he threw her down, run over her, run down Stairs and into the Street directly to the Thames in his Shirt, the Nurse running after him, and calling to the Watch to stop him; but the Watchmen frighted at the Man, and afraid to touch him, let him go on; upon which he ran down to the Stillyard Stairs, threw away his Shirt, and plung’d into the Thames, and, being a good swimmer, swam quite over the River; and the Tide being coming in, as they call it, that is running West-ward, he reached the Land not till he came about the Falcon Stairs, where landing, and finding no People there, it being in the Night, he ran about the Streets there, Naked as he was, for a good while, when it being by that time High-water, he takes the River again, and swam back to the Still-yard, landed, ran up the Streets again to his own House, knocking at the Door, went up the Stairs, and into his Bed again; and that this terrible Experiment cur’d him of the Plague, that is to say, that the violent Motion of his Arms and Legs stretch’d the Parts where the Swellings he had upon him were, that is to say under his Arms and his Groin, and caused them to ripen and break; and that the cold of the Water abated the Fever in his Blood.

I have only to add, that I do not relate this any more than some of the other, as a Fact within my own Knowledge, so as that I can vouch the Truth of them, and especially that of the Man being cur’d by the extravagant Adventure, which I confess I do not think very possible, but it may serve to confirm the many desperate Things which the distress’d People falling into, Deliriums, and what we call Lightheadedness, were frequently run upon at that time, and how infinitely more such there wou’d ha’ been, if such People had not been confin’d by the shutting up of Houses; and this I take to be the best, if not the only good thing which was perform’d by that severe Method.

On the other Hand, the Complaints and the Murmurings were very bitter against the thing itself.

It would pierce the Hearts of all that came by to hear the piteous Cries of those infected People, who being thus out of their Understandings by the Violence of their Pain, or the heat of their Blood, were either shut in, or perhaps ty’d in their Beds and Chairs, to prevent their doing themselves Hurt, and who wou’d make a dreadful outcry at their being confin’d, and at their being not permitted to die at large, as they call’d it, and as they wou’d ha’ done before.

This running of distemper’d People about the Streets was very dismal, and the Magistrates did their utmost to prevent it, but as it was generally in the Night and always sudden, when such attempts were made, the Officers cou’d not be at hand to prevent it, and even when any got out in the Day, the Officers appointed did not care to meddle with them, because, as they were all grievously infected to be sure when they were come to that Height, so they were more than ordinarily infectious, and it was one of the most dangerous Things that cou’d be to touch them; on the other Hand, they generally ran on, not knowing what they did, till they dropp’d down stark Dead, or till they had exhausted their Spirits so, as that they wou’d fall and then die in perhaps half an Hour or an Hour, and which was most piteous to hear, they were sure to come to themselves intirely in that half Hour or Hour, and then to make most grievous and piercing Cries and Lamentations in the deep afflicting Sense of the Condition they were in. This was much of it before the Order for shutting up of Houses was strictly put in Execution, for at first the Watchmen were not so vigorous and severe, as they were afterward in the keeping the People in; that is to say, before they were, I mean some of them, severely punish’d for their Neglect, failing in their Duty, and letting People who were under their Care slip away, or conniving at their going abroad whether sick or well. But after they saw the Officers appointed to examine into their Conduct, were resolv’d to have them do their Duty, or be punish’d for the omission, they were more exact, and the People were strictly restrain’d; which was a thing they took so ill, and bore so impatiently, that their Discontents can hardly be describ’d: But there was an absolute Necessity for it, that must be confess’d, unless some other Measures had been timely enter’d upon, and it was too late for that.

Had not this particular of the Sick’s been restrain’d as above, been our Case at that time, London wou’d ha’ been the most dreadful Place that ever was in the World; there wou’d for ought I know have as many People dy’d in the Streets as dy’d in their Houses; for when the Distemper was at its height, it generally made them Raving and Delirious, and when they were so, they wou’d never be perswaded to keep in their Beds but by Force; and many who were not ty’d, threw themselves out of Windows, when they found they cou’d not get leave to go out of their Doors.

It was for want of People conversing one with another, in this time of Calamity, that it was impossible any particular Person cou’d come at the Knowledge of all the extraordinary Cases that occurr’d in different Families; and particularly I believe it was never known to this Day how many People in their Deliriums drowned themselves in the Thames, and in the River which runs from the Marshes by Hackney, which we generally call’d Ware River, or Hackney River; as to those which were set down in the Weekly Bill, they were indeed few; nor cou’d it be known of any of those, whether they drowned themselves by Accident or not: But I believe, I might reckon up more, who, within the compass of my Knowledge or Observation, really drowned themselves in that Year, than are put down in the Bill of all put together, for many of the Bodies were never found, who yet were known to be so lost; and the like in other Methods of Self-Destruction. There was also One Man in or about Whitecross-street, burnt himself to Death in his Bed; some said it was done by himself, others that it was by the Treachery of the Nurse that attended him; but that he had the Plague upon him was agreed by all.

It was a merciful Disposition of Providence also, and which I have many times thought of at that time, that no Fires, or no considerable ones at least, happen’d in the City, during that Year, which, if it had been otherwise, would have been very dreadful; and either the People must have let them alone unquenched, or have come together in great Crowds and Throngs, unconcern’d at the Danger of the Infection, not concerned at the Houses they went into, at the Goods they handled, or at the Persons or the People they came among: But so it was that excepting that in Cripplegate Parish, and two or three little Eruptions of Fires, which were presently extinguish’d, there was no Disaster of that kind happen’d in the whole Year. They told us a Story of a House in a Place call’d Swan-Alley, passing from Goswell-street near the End of Oldstreet into St. John-street, that a Family was infected there, in so terrible a Manner that every one of the House died; the last Person lay dead on the Floor, and as it is supposed, had laid her self all along to die just before the Fire; the Fire, it seems had fallen from its Place, being of Wood, and had taken hold of the Boards and the Joists they lay on, and burnt as far as just to the Body, but had not taken hold of the dead Body, tho’ she had little more than her Shift on, and had gone out of itself, not hurting the Rest of the House, tho’ it was a slight Timber House. How true this might be, I do not determine, but the City being to suffer severely the next Year by Fire, this Year it felt very little of that Calamity.

Indeed considering the Deliriums, which the Agony threw People into, and how I have mention’d in their Madness, when they were alone, they did many desperate Things; it was very strange there were no more Disasters of that kind.

It has been frequently ask’d me, and I cannot say, that I ever knew how to give a direct Answer to it, How it came to pass that so many infected People appear’d abroad in the Streets, at the same time that the Houses which were infected were so vigilantly searched, and all of them shut up and guarded as they were.

I confess, I know not what Answer to give to this, unless it be this, that in so great and populous a City as this is, it was impossible to discover every House that was infected as soon as it was so, or to shut up all the Houses that were infected: so that People had the Liberty of going about the Streets, even where they pleased, unless they were known to belong to such and such infected Houses.

It is true, that as several Physicians told my Lord Mayor, the Fury of the Contagion was such at some particular Times, and People sicken’d so fast, and died so soon, that it was impossible and indeed to no purpose to go about to enquire who was sick and who was well, or to shut them up with such Exactness, as the thing required; almost every House in a whole Street being infected, and in many Places every Person in some of the Houses; and that which was still worse, by the time that the Houses were known to be infected, most of the Persons infected would be stone dead, and the rest run away for Fear of being shut up; so that it was to very small Purpose, to call them infected Houses and shut them up; the Infection having ravaged, and taken its Leave of the House, before it was really known, that the Family was any way touch’d.

This might be sufficient to convince any reasonable Person, that as it was not in the Power of the Magistrates, or of any human Methods or Policy, to prevent the spreading the Infection; so that this way of shutting up of Houses was perfectly insufficient for that End. Indeed it seemed to have no manner of publick Good in it, equal or proportionable to the grievous Burthen that it was to the particular Families, that were so shut up; and as far as I was employed by the publick in directing that Severity, I frequently found occasion to see, that it was incapable of answering the End. For Example as I was desired as a Visitor or Examiner to enquire into the Particulars of several Families which were infected, we scarce came to any House where the Plague had visibly appear’d in the Family, but that some of the Family were Fled and gone; the Magistrates would resent this, and charge the Examiners with being remiss in their Examination or Inspection: But by that means Houses were long infected before it was known. Now, as I was in this dangerous Office but half the appointed time, which was two Months, it was long enough to inform myself, that we were no way capable of coming at the Knowledge of the true state of any Family, but by enquiring at the Door, or of the Neighbours; as for going into every House to search, that was a part no Authority wou’d offer to impose on the Inhabitants, or any Citizen wou’d undertake, for it wou’d ha’ been exposing us to certain Infection and Death, and to the Ruine of our own Families as well as of ourselves, nor wou’d any Citizen of Probity, and that cou’d be depended upon, have staid in the Town, if they had been made liable to such a Severity.

Seeing then that we cou’d come at the certainty of Things by no Method but that of Enquiry of the Neighbours, or of the Family, and on that we cou’d not justly depend, it was not possible, but that the incertainty of this Matter wou’d remain as above.

It is true, Masters of Families were bound by the Order, to give Notice to the Examiner of the Place wherein he liv’d, within two Hours after he shou’d discover it, of any Person being sick in his House, that is to say, having Signs of the Infection, but they found so many ways to evade this, and excuse their Negligence, that they seldom gave that Notice, till they had taken Measures to have every one Escape out of the House, who had a mind to Escape, whether they were Sick or Sound; and while this was so, it is easie to see, that the shutting up of Houses was no way to be depended upon, as a sufficient Method for putting a stop to the Infection, because, as I have said elsewhere, many of those that so went out of those infected Houses, had the Plague really upon them, tho’ they might really think themselves Sound: And some of these were the People that walk’d the Streets till they fell down Dead, not that they were suddenly struck with the Distemper, as with a Bullet that kill’d with the Stroke, but that they really had the Infection in their Blood long before, only, that, as it prey’d secretly on the Vitals, it appear’d not till it seiz’d the Heart with a mortal Power, and the Patient died in a Moment, as with a sudden Fainting, or an Apoplectick Fit.

I know that some, even of our Physicians, thought, for a time, that those People that so died in the Streets, were seiz’d but that Moment they fell, as if they had been touch’d by a Stroke from Heaven, as Men are kill’d by a flash of Lightning; but they found Reason to alter their Opinion afterward; for upon examining the Bodies of such after they were Dead, they always either had Tokens upon them, or other evident Proofs of the Distemper having been longer upon them, than they had otherwise expected.

This often was the Reason that, as I have said, we, that were Examiners, were not able to come at the Knowledge of the Infection being enter’d into a House, till it was too late to shut it up; and sometimes not till the People that were left, were all Dead. In Petticoat-Lane two Houses together were infected, and several People sick; but the Distemper was so well conceal’d, the Examiner, who was my Neighbour, got no Knowledge of it, till Notice was sent him that the People were all Dead, and that the Carts should call there to fetch them away. The two Heads of the Families concerted their Measures, and so order’d their Matters, as that when the Examiner was in the Neighbourhood, they appeared generally one at a time, and answered, that is, lied for one another, or got some of the Neighbourhood to say they were all in Health, and perhaps knew no better, till Death making it impossible to keep it any longer as a Secret, the dead-Carts were call’d in the Night, the Houses to both, and so it became publick: But when the Examiner order’d the Constable to shut up the Houses, there was no Body left in them but three People, two in one House, and one in the other just dying, and a Nurse in each House, who acknowledg’d that they had buried five before, that the Houses had been infected nine or ten Days, and that for all the rest of the two Families, which were many, they were gone, some sick, some well, or whether sick or well could not be known.

In like manner, at another House in the same Lane, a Man having his Family infected, but very unwilling to be shut up, when he could conceal it no longer, shut up himself; that is to say, he set the great red Cross upon his Door with the words LORD HAVE MERCY UPON US; and so deluded the Examiner, who suppos’d it had been done by the Constable, by Order of the other Examiner, for there were two Examiners to every District or Precinct; by this means he had free egress and regress into his House again, and out of it, as he pleas’d notwithstanding it was infected; till at length his Stratagem was found out, and then he, with the sound part of his Servants and Family, made off and escaped; so they were not shut up at all.

These things made it very hard, if not impossible, as I have said, to prevent the spreading of an Infection by the shutting up of Houses, unless the People would think the shutting up of their Houses no Grievance, and be so willing to have it done, as that they wou’d give Notice duly and faithfully to the Magistrates of their being infected, as soon as it was known by themselves: But as that can not be expected from them, and the Examiners can not be supposed, as above, to go into their Houses to visit and search, all the good of shutting up Houses, will be defeated, and few Houses will be shut up in time, except those of the Poor, who can not conceal it, and of some People who will be discover’d by the Terror and Consternation which the Thing put them into.

I got myself discharg’d of the dangerous Office I was in, as soon as I cou’d get another admitted, who I had obtain’d for a little Money to accept of it; and so, instead of serving the two Months, which was directed, I was not above three Weeks in it; and a great while too, considering it was in the Month of August, at which time the Distemper began to rage with great Violence at our end of the Town.*

In the execution of this Office, I cou’d not refrain speaking my Opinion among my Neighbours, as to this shutting up the People in their Houses; in which we saw most evidently the Severities that were used tho’ grievous in themselves, had also this particular Objection against them, namely, that they did not answer the End, as I have said, but that the distemper’d People went Day by Day about the Streets; and it was our united Opinion, that a Method to have removed the Sound from the Sick in Case of a particular House being visited, wou’d ha’ been much more reasonable on many Accounts, leaving no Body with the sick Persons, but such as shou’d on such Occasion request to stay and declare themselves content to be shut up with them.

Our Scheme for removing those that were Sound from those that were Sick, was only in such Houses as were infected, and confining the sick was no Confinement; those that cou’d not stir, wou’d not complain, while they were in their Senses, and while they had the Power of judging: Indeed, when they came to be Delirious and Light-headed, then they wou’d cry out of the Cruelty of being confin’d; but for the removal of those that were well, we thought it highly reasonable and just, for their own sakes, they shou’d be remov’d from the Sick, and that, for other People’s Safety, they shou’d keep retir’d for a while, to see that they were sound, and might not infect others; and we thought twenty or thirty Days enough for this.

Now certainly, if Houses had been provided on purpose for those that were sound to perform this demy Quarantine in, they wou’d have much less Reason to think themselves injur’d in such a restraint, than in being confin’d with infected People, in the Houses where they liv’d.

It is here, however, to be observ’d, that after the Funerals became so many, that People could not Toll the Bell, Mourn, or Weep, or wear Black for one another, as they did before; no, nor so much as make Coffins for those that died; so after a while the fury of the Infection appeared to be so encreased, that in short, they shut up no Houses at all; it seem’d enough that all the Remedies of that Kind had been used till they were found fruitless, and that the Plague spread itself with an irresistible Fury, so that, as the Fire the succeeding Year, spread itself and burnt with such Violence, that the Citizens in Despair, gave over their Endeavours to extinguish it, so in the Plague, it came at last to such Violence that the People sat still looking at one another, and seem’d quite abandon’d to Despair; whole Streets seem’d to be desolated, and not to be shut up only, but to be emptied of their Inhabitants; Doors were left open, Windows stood shattering with the Wind in empty Houses, for want of People to shut them: In a Word, People began to give up themselves to their Fears, and to think that all regulations and Methods were in vain, and that there was nothing to be hoped for, but an universal Desolation; and it was even in the height of this general Despair, that it pleased God to stay his Hand, and to slacken the Fury of the Contagion, in such a manner as was even surprizing like its beginning, and demonstrated it to be his own particular Hand, and that above, if not without the Agency of Means, as I shall take Notice of in its proper Place.

But I must still speak of the Plague as in its height, raging even to Desolation, and the People under the most dreadful Consternation, even, as I have said, to Despair. It is hardly credible to what Excesses the Passions of Men carry’d them in this Extremity of the Distemper; and this Part, I think, was as moving as the rest; What cou’d affect a Man in his full Power of Reflection; and what could make deeper Impressions on the Soul, than to see a Man almost Naked and got out of his House, or perhaps out of his Bed into the Street, come out of Harrow-Alley, a populous Conjunction or Collection of Alleys, Courts, and Passages, in the Butcher-row in White-chappel? I say, What could be more Affecting, than to see this poor Man come out into the open Street, run Dancing and Singing, and making a thousand antick Gestures, with five or six Women and Children running after him, crying, and calling upon him, for the Lord’s sake to come back, and entreating the help of others to bring him back, but all in vain, no Body daring to lay a Hand upon him, or to come near him.

This was a most grievous and afflicting thing to me, who saw it all from my own Windows; for all this while, the poor afflicted Man, was, as I observ’d it, even then in the utmost Agony of Pain, having, as they said, two Swellings upon him, which cou’d not be brought to break, or to suppurate; but by laying strong Causticks on them, the Surgeons had, it seems, hopes to break them, which Causticks were then upon him, burning his Flesh as with a hot Iron: I cannot say what became of this poor Man, but I think he continu’d roving about in that manner till he fell down and Died.

No wonder the Aspect of the City itself was frightful, the usual concourse of People in the Streets, and which used to be supplied from our end of the Town, was abated; the Exchange was not kept shut* indeed, but it was no more frequented; the Fires were lost;* they had been almost extinguished for some Days by a very smart and hasty Rain: But that was not all, some of the Physicians insisted that they were not only no Benefit, but injurious* to the Health of People: This they made a loud Clamour about, and complained to the Lord Mayor about it: On the other Hand, others of the same Faculty, and Eminent too, oppos’d them, and gave their Reasons why the Fires were and must be useful to asswage the Violence of the Distemper. I cannot give a full Account of their Arguments on both Sides, only this I remember, that they cavil’d very much with one another; some were for Fires, but that they must be made of Wood and not Coal,* and of particular sorts of Wood too, such as Fir in particular, or Cedar, because of the strong effluvia of Turpentine; Others were for Coal and not Wood, because of the Sulphur and Bitumen; and others were for neither one or other. Upon the whole, the Lord Mayor ordered no more Fires, and especially on this Account, namely, that the Plague was so fierce that they saw evidently it defied all Means and rather seemed to encrease than decrease upon any application to check and abate it; and yet this Amazement of the Magistrates, proceeded rather from want of being able to apply any Means successfully, than from any unwillingness either to expose themselves, or undertake the Care and Weight of Business; for, to do them Justice, they neither spared their Pains or their Persons; but nothing answer’d, the Infection rag’d, and the People were now frighted and terrified to the last Degree, so that, as I may say, they gave themselves up, and, as I mention’d above, abandon’d themselves to their Despair.

But let me observe here, that when I say the People abandon’d themselves to Despair, I do not mean to what Men call a religious Despair, or a Despair of their eternal State, but I mean a Despair of their being able to escape the Infection, or to out-live the Plague, which they saw was so raging and so irresistible in its Force, that indeed few People that were touch’d with it in its height about August, and September, escap’d: And, which is very particular, contrary to its ordinary Operation in June and July, and the beginning of August, when, as I have observ’d many were infected, and continued so many Days, and then went off, after having had the Poison in their Blood a long time; but now on the contrary, most of the People who were taken during the two last Weeks in August, and in the three first Weeks in September, generally died in two or three Days at farthest, and many the very same Day they were taken; Whether the Dog-days, or as our Astrologers pretended to express themselves, the Influence of the Dog-Star* had that malignant Effect; or all those who had the seeds of Infection before in them, brought it up to a maturity at that time altogether I know not; but this was the time when it was reported, that above 3000 People died in one Night; and they that wou’d have us believe they more critically observ’d it, pretend to say, that they all died within the space of two Hours, (viz.) Between the Hours of One and three in the Morning.

As to the Suddenness of People’s dying at this time more than before, there were innumerable Instances of it, and I could name several in my Neighbourhood; one Family without the Barrs, and not far from me, were all seemingly well on the Monday, being Ten in Family, that Evening one Maid and one Apprentice were taken ill, and dy’d the next Morning, when the other Apprentice and two Children were touch’d, whereof one dy’d the same Evening, and the other two on Wednesday: In a Word, by Saturday at Noon, the Master, Mistress, four Children and four Servants were all gone, and the House left entirely empty, except an ancient Woman, who came in to take Charge of the Goods for the Master of the Family’s Brother, who liv’d not far off, and who had not been sick.

Many Houses were then left desolate, all the People being carry’d away dead, and especially in an Alley farther, on the same Side beyond the Barrs, going in at the Sign of Moses and Aaron; there were several Houses together, which (they said) had not one Person left alive in them, and some that dy’d last in several of those Houses, were left a little too long before they were fetch’d out to be bury’d; the Reason of which was not as some have written very untruly, that the living were not sufficient to bury the dead; but that the Mortality was so great in the Yard or Alley, that there was no Body left to give Notice to the Buriers or Sextons, that there were any dead Bodies there to be bury’d. It was said, how true I know not, that some of those Bodies were so much corrupted, and so rotten, that it was with Difficulty they were carry’d; and as the Carts could not come any nearer than to the Alley-Gate in the high Street, it was so much the more difficult to bring them along; but I am not certain how many Bodies were then left, I am sure that ordinarily it was not so.

As I have mention’d how the People were brought into a Condition to despair of Life and abandon themselves, so this very Thing had a strange Effect among us for three or four Weeks, that is, it made them bold and venturous, they were no more shy of one another, or restrained within Doors, but went any where and every where, and began to converse; one would say to another, I do not ask you how you are, or say how I am, it is certain we shall all go, so ’tis no Matter who is sick or who is sound, and so they run desperately into any Place or any Company.

As it brought the People into publick Company, so it was surprizing how it brought them to crowd into the Churches, they inquir’d no more into who they sat near to, or far from, what offensive Smells they met with, or what condition the People seemed to be in, but looking upon themselves all as so many dead Corpses, they came to the Churches without the least Caution, and crowded together, as if their Lives were of no Consequence, compar’d to the Work which they came about there: Indeed, the Zeal which they shew’d in Coming, and the Earnestness and Affection they shew’d in their Attention to what they heard, made it manifest what a Value People would all put upon the Worship of God, if they thought every Day they attended at the Church that it would be their Last.

Nor was it without other strange Effects, for it took away all Manner of Prejudice at, or Scruple about the Person who they found in the Pulpit when they came to the Churches. It cannot be doubted, but that many of the Ministers of the Parish-Churches were cut off among others in so common and so dreadful a Calamity; and others had not Courage enough to stand it, but removed into the Country as they found Means for Escape; as then some Parish-Churches were quite vacant and forsaken, the People made no Scruple of desiring such Dissenters as had been a few Years before depriv’d of their Livings, by Virtue of the Act of Parliament call’d The Act of Uniformity,* to preach in the Churches, nor did the Church Ministers in that Case make any Difficulty of accepting their Assistance, so that many of those who they called silenced Ministers, had their Mouths open’d on this Occasion, and preach’d publickly to the People.

Here we may observe, and I hope it will not be amiss to take notice of it, that a near View of Death would soon reconcile Men of good Principles one to another, and that it is chiefly owing to our easy Scituation in Life, and our putting these Things far from us, that our Breaches are fomented, ill Blood continued, Prejudices, Breach of Charity and of Christian Union so much kept and so far carry’d on among us, as it is: Another Plague Year would reconcile all these Differences, a close conversing with Death, or with Diseases that threaten Death, would scum off the Gall from our Tempers, remove the Animosities among us, and bring us to see with differing Eyes, than those which we look’d on Things with before; as the People who had been used to join with the Church, were reconcil’d at this Time, with the admitting the Dissenters to preach to them: So the Dissenters, who with an uncommon Prejudice, had broken off from the Communion of the Church of England, were now content to come to their Parish-Churches, and to conform to the Worship which they did not approve of before; but as the Terror of the Infection abated, those Things all returned again to their less desirable Channel, and to the Course they were in before.

I mention this but historically, I have no mind to enter into Arguments to move either, or both Sides to a more charitable Compliance one with another; I do not see that it is probable such a Discourse would be either suitable or successful; the Breaches seem rather to widen, and tend to a widening farther, than to closing, and who am I that I should think myself able to influence either one Side or other? But this I may repeat again, that ’tis evident Death will reconcile us all; on the other Side the Grave we shall be all Brethren again: In Heaven, whither I hope we may come from all Parties and Perswasions, we shall find neither Prejudice or Scruple; there we shall be of one Principle and of one Opinion, why we cannot be content to go Hand in Hand to the Place where we shall join Heart and Hand without the least Hesitation, and with the most compleat Harmony and Affection; I say, why we cannot do so here I can say nothing to, neither shall I say any thing more of it, but that it remains to be lamented.

I could dwell a great while upon the Calamities of this dreadful time, and go on to describe the Objects that appear’d among us every Day, the dreadful Extravagancies which the Distraction of sick People drove them into; how the Streets began now to be fuller of frightful Objects, and Families to be made even a Terror to themselves: But after I have told you, as I have above, that One Man being tyed in his Bed, and finding no other Way to deliver himself, set the Bed on fire with his Candle, which unhappily stood within his reach, and Burnt himself in his Bed. And how another, by the insufferable Torment he bore, daunced and sung naked in the Streets, not knowing one Extasie from another, I say, after I have mention’d these Things, What can be added more? What can be said to represent the Misery of these Times, more lively to the Reader, or to give him a more perfect Idea of a complicated Distress?

I must acknowledge that this time was Terrible, that I was sometimes at the End of all my Resolutions, and that I had not the Courage that I had at the Beginning. As the Extremity brought other People abroad, it drove me Home, and except, having made my Voyage down to Blackwall and Greenwich, as I have related, which was an Excursion, I kept afterwards very much within Doors, as I had for about a Fortnight before; I have said already, that I repented several times that I had ventur’d to stay in Town, and had not gone away with my Brother, and his Family, but it was too late for that now; and after I had retreated and stay’d within Doors a good while, before my Impatience led me Abroad, then they call’d me, as I have said, to an ugly and dangerous Office, which brought me out again; but as that was expir’d, while the hight of the Distemper lasted, I retir’d again, and continued close ten or twelve Days more. During which many dismal Spectacles represented themselves in my View, out of my own Windows, and in our own Street, as that particularly from Harrow-Alley, of the poor outrageous Creature which danced and sung in his Agony, and many others there were: Scarce a Day or Night pass’d over, but some dismal Thing or other happened at the End of that Harrow-Alley, which was a Place full of poor People, most of them belonging to the Butchers, or to Employments depending upon the Butchery.

Sometimes Heaps and Throngs of People would burst out of that Alley, most of them Women, making a dreadful Clamour, mixt or Compounded of Skreetches, Cryings and Calling one another, that we could not conceive what to make of it; almost all the dead Part of the Night the dead Cart stood at the End of that Alley, for if it went in it could not well turn again, and could go in but a little Way. There, I say, it stood to receive dead Bodies, and as the Church-Yard was but a little Way off, if it went away full it would soon be back again: It is impossible to describe the most horrible Cries and Noise the poor People would make at their bringing the dead Bodies of their Children and Friends out to the Cart, and by the Number one would have thought, there had been none left behind, or that there were People enough for a small City liveing in those Places: Several times they cryed Murther, sometimes Fire; but it was easie to perceive it was all Distraction, and the Complaints of Distress’d and distemper’d People.

I believe it was every where thus at that time, for the Plague rag’d for six or seven Weeks beyond all that I have express’d; and came even to such a height, that in the Extremity, they began to break into that excellent Order, of which I have spoken so much, in behalf of the Magistrates, namely, that no dead Bodies were seen in the Streets or Burials in the Day-time for there was a Necessity, in this Extremity, to bear with its being otherwise, for a little while.

One thing I cannot omit here, and indeed I thought it was extraordinary, at least, it seemed a remarkable Hand of Divine Justice, (viz.) That all the Predictors, Astrologers, Fortune-tellers, and what they call’d cunning-Men, Conjurers, and the like; calculators of Nativities, and dreamers of Dreams, and such People, were gone and vanish’d, not one of them was to be found: I am, verily, perswaded that a great Number of them fell in the heat of the Calamity, having ventured to stay upon the Prospect of getting great Estates; and indeed their Gain was but too great for a time through the Madness and Folly of the People; but now they were silent, many of them went to their long Home, not able to foretel their own Fate, or to calculate their own Nativities; some have been critical enough to say, that every one of them dy’d; I dare not affirm that; but this I must own, that I never heard of one of them that ever appear’d after the Calamity was over.

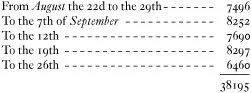

But to return to my particular Observations, during this dreadful part of the Visitation: I am now come, as I have said, to the Month of September, which was the most dreadful of its kind, I believe, that ever London saw; for by all the Accounts which I have seen of the preceding Visitations which have been in London, nothing has been like it; the Number in the Weekly Bill amounting to almost 40,000* from the 22d of August, to the 26th of September, being but five Weeks, the particulars of the Bills are as follows, (viz.)

This was a prodigious Number of itself, but if I should add the Reasons which I have to believe that this Account was deficient, and how deficient it was, you would with me, make no Scruple to believe that there died above ten Thousand a Week for all those Weeks, one Week with another, and a proportion for several Weeks both before and after: The Confusion among the People, especially within the City at that time, was inexpressible; the Terror was so great at last, that the Courage of the People appointed to carry away the Dead, began to fail them; nay, several of them died altho’ they had the Distemper before, and were recover’d; and some of them drop’d down when they have been carrying the Bodies even at the Pitside, and just ready to throw them in; and this Confusion was greater in the City, because they had flatter’d themselves with Hopes of escaping: And thought the bitterness of Death was past: One Cart they told us, going up Shoreditch, was forsaken of the Drivers, or being left to one Man to drive, he died in the Street, and the Horses going on, overthrew the Cart, and left the Bodies, some thrown out here, some there, in a dismal manner; Another Cart was it seems found in the great Pit in Finsbury Fields, the Driver being Dead, or having been gone and abandon’d it, and the Horses running too near it, the Cart fell in and drew the Horses in also: It was suggested that the Driver was thrown in with it, and that the Cart fell upon him, by Reason his Whip was seen to be in the Pit among the Bodies; but that, I suppose, cou’d not be certain.

In our Parish of Aldgate, the dead-Carts were several times, as I have heard, found standing at the Church-yard Gate, full of dead Bodies, but neither Bell man or Driver, or any one else with it; neither in these, or many other Cases, did they know what Bodies they had in their Cart, for sometimes they were let down with Ropes out of Balconies and out of Windows; and sometimes the Bearers brought them to the Cart, sometimes other People; nor, as the Men themselves said, did they trouble themselves to keep any Account of the Numbers.

The Vigilance of the Magistrate was now put to the utmost Trial, and it must be confess’d, can never be enough acknowledg’d on this Occasion also; whatever Expence or Trouble they were at, two Things were never neglected in the City or Suburbs either.

1. Provisions were always to be had in full Plenty, and the Price not much rais’d neither, hardly worth speaking.

2. No dead Bodies lay unburied or uncovered; and if one walk’d from one end of the City to another, no Funeral or sign of it was to be seen in the Day-time,* except a little, as I have said above, in the three first Weeks in September.

This last Article perhaps will hardly be believ’d, when some Accounts which others have published since that shall be seen, wherein they say, that the Dead lay unburied, which I am assured was utterly false; at least, if it had been any where so, it must ha’ been in Houses where the Living were gone from the Dead, having found means, as I have observed, to Escape, and where no Notice was given to the Officers: All which amounts to nothing at all in the Case in Hand; for this I am positive in, having myself been employ’d a little in the Direction of that part in the Parish in which I liv’d, and where as great a Desolation was made in proportion to the Number of Inhabitants as was any where. I say, I am sure that there were no dead Bodies remain’d unburied; that is to say, none that the proper Officers knew of; none for want of People to carry them off, and Buriers to put them into the Ground and cover them; and this is sufficient to the Argument; for what might lie in Houses and Holes as in Moses and Aaron Alley is nothing; for it is most certain, they were buried as soon as they were found. As to the first Article, namely, of Provisions, the scarcity or dearness, tho’ I have mention’d it before, and shall speak of it again; yet I must observe here,

(1.) The Price of Bread in particular was not much raised;* for in the beginning of the Year (viz.) In the first Week in March, the Penny Wheaten Loaf was ten Ounces and a half; and in the height of the Contagion, it was to be had at nine Ounces and an half, and never dearer, no not all that Season: And about the beginning of November it was sold ten Ounces and a half again; the like of which, I believe, was never heard of in any City, under so dreadful a Visitation before.

(2.) Neither was there (which I wondred much at) any want of Bakers or Ovens kept open to supply the People with Bread; but this was indeed alledg’d by some Families, viz. That their Maid-Servants going to the Bake-houses with their Dough to be baked, which was then the Custom, sometimes came Home with the Sickness, that is to say, the Plague upon them.

In all this dreadful Visitation, there were, as I have said before, but two Pest-houses* made use of, viz. One in the Fields beyond Old-Street, and one in Westminster; neither was there any Compulsion us’d in carrying People thither: Indeed there was no need of Compulsion in the Case, for there were Thousands of poor distressed People, who having no Help, or Conveniences, or Supplies but of Charity, would have been very glad to have been carryed thither, and been taken Care of, which indeed was the only thing that, I think, was wanting in the whole publick Management of the City; seeing no Body was here allow’d to be brought to the Pest-house, but where Money was given, or Security for Money, either at their introducing, or upon their being cur’d and sent out; for very many were sent out again whole, and very good Physicians were appointed to those Places, so that many People did very well there, of which I shall make Mention again. The principal Sort of People sent thither were, as I have said, Servants, who got the Distemper by going of Errands to fetch Necessaries to the Families where they liv’d; and who in that Case, if they came Home sick, were remov’d to preserve the rest of the House; and they were so well look’d after there in all the time of the Visitation, that there was but 156 buried in all at the London Pest-house, and 159 at that of Westminster.

By having more Pest-houses, I am far from meaning a forcing all People into such Places. Had the shutting up of Houses been omitted, and the Sick hurried out of their Dwellings to Pest-houses, as some proposed it seems, at that time as well as since, it would certainly have been much worse than it was; the very removing the Sick would have been a spreading of the Infection, and the rather because that removing could not effectually clear the House, where the sick Person was, of the Distemper, and the rest of the Family being then left at Liberty would certainly spread it among others.

The Methods also in private Families, which would have been universally used to have concealed the Distemper, and to have conceal’d the Persons being sick, would have been such that the Distemper would sometimes have seiz’d a whole Family before any Visitors or Examiners could have known of it: On the other hand, the prodigious Numbers which would have been sick at a time, would have exceeded all the Capacity of publick Pest-houses to receive them, or of publick Officers to discover and remove them.

This was well considered in those Days, and I have heard them talk of it often: The Magistrates had enough to do to bring People to submit to having their Houses shut up, and many Ways they deceived the Watchmen, and got out, as I have observed: But that Difficulty made it apparent, that they would have found it impracticable to have gone the other way to Work; for they could never have forced the sick People out of their Beds and out of their Dwellings; it must not have been my Lord Mayor’s Officers, but an Army of Officers that must have attempted it; and the People, on the other hand, would have been enrag’d and desperate, and would have kill’d those that should have offered to have meddled with them or with their Children and Relations, whatever had befallen them for it; so that they would have made the People, who, as it was, were in the most terrible Distraction imaginable; I say, they would have made them stark mad; whereas the Magistrates found it proper on several Accounts to treat them with Lenity and Compassion, and not with Violence and Terror, such as dragging the Sick out of their Houses, or obliging them to remove themselves would have been.

This leads me again to mention the Time, when the Plague first began, that is to say, when it became certain that it would spread over the whole Town, when, as I have said, the better sort of People first took the Alarm, and began to hurry themselves out of Town: It was true, as I observ’d in its Place, that the Throng was so great, and the Coaches, Horses, Waggons and Carts were so many, driving and dragging the People away, that it look’d as if all the City was running away; and had any Regulations been publish’d that had been terrifying at that time, especially such as would pretend to dispose of the People, otherwise than they would dispose of themselves, it would have put both the City and Suburbs into the utmost Confusion.

But the Magistrates wisely caus’d the People to be encourag’d, made very good By-Laws for the regulating the Citizens, keeping good Order in the Streets, and making every thing as eligible as possible to all Sorts of People.

In the first Place, the Lord Mayor and the Sheriffs, the Court of Aldermen, and a certain Number of the Common Council-Men, or their Deputies came to a Resolution and published it, viz. ‘That they would not quit the City themselves, but that they would be always at hand for the preserving good Order in every Place, and for the doing Justice on all Occasions; as also for the distributing the publick Charity to the Poor; and in a Word, for the doing the Duty, and discharging the Trust repos’d in them by the Citizens to the utmost of their Power.’

In Pursuance of these Orders, the Lord Mayor, Sheriffs, &c.

1 comment