Between Them

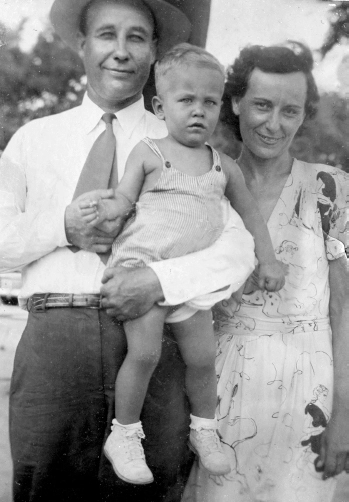

Parker, Richard, and Edna, New Orleans, V-J Day 1945

Kristina

Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Author’s Note

- Gone: Remembering My Father

- My Mother, In Memory

- Afterword

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Also by Richard Ford

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Guide

- Cover

- Contents

- Chapter 1

- iii

- iv

- ix

- v

- vi

- vii

- viii

- x

- 1

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

- 159

- 160

- 161

- 162

- 163

- 164

- 165

- 166

- 167

- 168

- 169

- 170

- 171

- 172

- 173

- 174

- 175

- 177

- 178

- 179

In writing these two memoirs—thirty years apart—I have permitted some inconsistencies to persist between the two, and I have allowed myself the lenience to retell certain events. Both of these choices, I hope, will remind the reader that I was one person raised by two very different people, each with a separate perspective to impress upon me, each trying to act in concert with the other, and each of whose eyes I tried to see the world through. Bringing up a son who can survive to adulthood must sometimes seem to parents little more than a dogged exercise in repetition, and an often futile but loving effort at consistency. In all cases, however, entering the past is a precarious business, since the past strives but always half-fails to make us who we are. RF

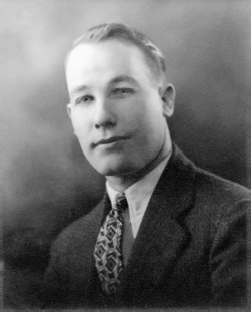

Parker Ford (date unknown)

Somewhere deep in my childhood, my father is coming home off the road on a Friday night. He is a traveling salesman. It is 1951 or ’52. He’s carrying with him lumpy, white butcher-paper packages full of boiled shrimp or tamales or oysters-by-the-pint he’s brought up from Louisiana. The shrimp and tamales steam up hot and damp off the slick papers when he opens them out. Lights in our small duplex on Congress Street in Jackson are switched on bright. My father, Parker Ford, is a large man—soft, heavy-seeming, smiling widely as if he knew a funny joke. He is excited to be home. He sniffs with pleasure. His blue eyes sparkle. My mother is standing beside him, relieved he’s back. She is buoyant, happy. He spreads the packages out onto the metal kitchen table top for us to see before we eat. It is as festive as life can possibly be. My father is home again.

Our—my and my mother’s—week has anticipated this arrival. “Edna, will you . . . ?” “Edna, did you . . . ?” “Son, son, son. . . .” I am in the middle of everything. Normal life—between his Monday leavings and the Friday nights when he comes back—normal life is the interstitial time. A time he doesn’t need to know about and that my mother saves him from. If something bad has happened, if she and I have had a row (always possible), if I have had trouble in school (also possible), this news will be covered over, manicured for his peace of mind. I don’t remember my mother ever saying “I’ll have to tell your father about this.” Or “Wait ’til your father comes home. . . .” Or “Your father will not like that. . . .” He confers—they confer—the administration of the week’s events, including my supervision, onto her. If he doesn’t have to hear it when he’s home—ebullient and smiling with packages—it can be assumed nothing so bad has gone on. Which is true and, to that extent, is fine with me.

HIS LARGE MALLEABLE, FLESHY FACE was given to smiling. His first face was always the smiling one. The long Irish lip.

1 comment