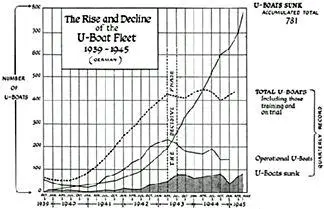

The single-handed British struggle against the U-boats, the magnetic mines, and the surface raiders in the first two and a half years of the war has already been described. The long-awaited supreme event of the American Alliance which arose from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour seemed at first to have increased our perils at sea. In 1940 four million tons of merchant shipping were lost, and more than four million tons in 1941. In 1942, after the United States

Closing the Ring

20

was our ally, nearly eight million tons of the augmented mass of Allied shipping had been sunk. Until the end of 1942, the U-boats sank ships faster than the Allies could build them. The foundation of all our hopes and schemes was the immense shipbuilding programme of the United States. By the beginning of 1943, the curve of new tonnage was rising sharply and losses fell. Before the end of that year, new tonnage at last surpassed losses at sea from all causes, and the second quarter saw, for the first time, U-boat losses exceed their rate of replacement. The time was presently to come when more U-boats would be sunk in the Atlantic than merchant ships. But before this lay a long and bitter conflict.

The Battle of the Atlantic was the dominating factor all through the war. Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea, or in

Closing the Ring

21

the air, depended ultimately on its outcome, and amid all other cares we viewed its changing fortunes day by day with hope or apprehension. The tale of hard and unremitting toil, often under conditions of acute discomfort and frustration and always in the presence of unseen danger, is lighted by incident and drama; but for the individual sailor or airman in the U-boat war there were few moments of exhilarating action to break the monotony of an endless succession of anxious, uneventful days. Vigilance could never be relaxed. Dire crisis might at any moment flash upon the scene with brilliant fortune or glare with mortal tragedy. Many gallant actions and incredible feats of endurance are recorded, but the deeds of those who perished will never be known. Our merchant seamen displayed their highest qualities, and the brotherhood of the sea was never more strikingly shown than in their determination to defeat the U-boat.

Important changes had been made in our operational commands. Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, who had gone to Washington as head of our Naval Mission, had been recalled in October 1942 to command the Allied Navies in “Torch.” Admiral Sir Percy Noble, who at “Derby House,” the Liverpool headquarters of the Western Approaches, had held the commanding post in the Battle of the Atlantic since the beginning of 1941, went to Washington, with his unequalled knowledge of the U-boat problem. In February 1943 Air-Marshal Slessor became Chief of the Coastal Air Command. These arrangements were vindicated by the results.

The Casablanca Conference had proclaimed the defeat of the U-boats as our first objective. In March 1943 an Atlantic

Closing the Ring

22

Convoy Conference met in Washington, under Admiral King, to pool all Allied resources in the Atlantic. This system did not amount to full unity of command. There was well-knit co-operation at all levels and complete accord at the top, but the two Allies approached the problem with differences of method. The United States had no organisation like our Coastal Command, through which on the British or reception side of the ocean air operations were controlled by a single authority. A high degree of flexibility had been attained. Formations could be rapidly switched from quiet to dangerous areas, and the command was being reinforced largely from American sources. In Washington control was exerted through a number of autonomous subordinate commands called “sea frontiers,”

each with its allotment of aircraft.

After the winter gales, which caused much damage to our escorts but also checked the U-boat attack, the month of February 1943 had shown an ugly increase in the hostile concentrations in the North Atlantic.

1 comment