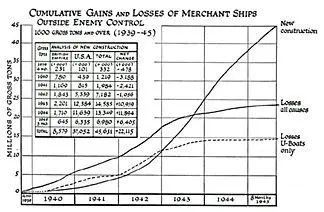

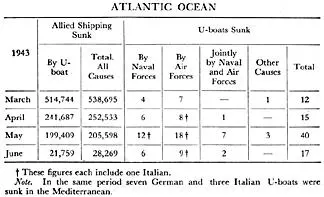

In spite of heavy losses, the number of operational U-boats at Admiral Doenitz’s disposal at the beginning of the year rose to two hundred and twelve. In March there were over a hundred of them constantly at sea, and the packs in which they hunted could no longer be evaded by skilful routeing. The issue had to be fought out by combined sea and air forces round the convoys themselves. Sinkings throughout the world rose to nearly seven hundred thousand tons in that month.

Amid these stresses a new agreement was reached in Washington whereby Britain and Canada assumed entire responsibility for convoys on the main North Atlantic route to Britain. The decisive battle with the U-boats was now

Closing the Ring

23

fought and won. Control was vested in two joint naval and air headquarters, one at Liverpool under a British and the other at Halifax under a Canadian admiral. Naval protection in the North Atlantic was henceforward provided by British and Canadian ships, the United States remaining responsible for their convoys to the Mediterranean and their own troop transports. In the air British, Canadian, and United States forces all complied with the day-to-day requirements of the joint commanders at Liverpool and Halifax.

The air gap in the North Atlantic southeast of Greenland was now closed by means of the very long-range (V.L.R.) Liberator squadrons based in Newfoundland and Iceland.

By April a shuttle service provided daylight air-cover along the whole route. The U-boat packs were kept underwater and harried continually, while the air and surface escort of the convoys coped with the attackers. We were now strong enough to form independent flotilla groups to act like cavalry divisions, apart from all escort duties. This I had long desired to see.

It was at this time that the H2S apparatus, described in Volume IV, , of which a number had been handed over somewhat reluctantly by our Bomber Command to Coastal Command, played a notable part. The Germans had learnt how to detect the comparatively long waves used in our earlier radar, and to dive before our flyers could attack them. It was many months before they discovered how to detect the very short wave used in our new method. Hitler complained that this single invention was the ruin of the U-boat campaign. This was an exaggeration.

Closing the Ring

24

In the Bay of Biscay however the Anglo-American air offensive was soon to make the life of U-boats in transit almost unbearable. The rocket now fired from aircraft was so damaging that the enemy started sending the U-boats through in groups on the surface, fighting off the aircraft with gunfire in daylight. This desperate experiment was vain. In March and April 1943 twenty-seven U-boats were destroyed in the Atlantic alone, more than half by air attack.

In April 1943 we could see the balance turn. Two hundred and thirty-five U-boats, the greatest number the Germans ever achieved, were in action. But their crews were beginning to waver. They could never feel safe. Their attacks, even when conditions were favourable, were no longer pressed home, and, during this month our shipping losses in the Atlantic fell by nearly three hundred thousand tons. In May alone forty U-boats perished in the Atlantic.

The German Admiralty watched their charts with strained attention, and at the end of the month Admiral Doenitz

Closing the Ring

25

recalled the remnants of his fleet from the North Atlantic to rest or to fight in less hazardous waters.

1 comment