God knows I have payment enough!” and then it sang again with its blessed, sweet voice.

“That’s the most delightful coquetry and flirtation we’ve ever seen,” said all the ladies, and they kept water in their mouths so they could cluck when someone talked to them. They thought they were nightingales too. Well, the footmen and chambermaids also let it be known that they were satisfied, and that says a lot since they are the most difficult to please. Yes, the nightingale was a great success!

It was going to remain at court and have its own cage, but freedom to walk out twice a day and once at night. Twelve servants were to go along with silk ribbons tied to the nightingale’s leg, and they were to hold on tightly. There was no pleasure to be had from walks like this!

The whole town talked about the remarkable bird, and if two people met each other, then the first said only “Night” and the other said “gale,” and then they sighed and understood each other. Eleven grocers named their children after the nightingale, but none of them could sing a note.

One day a big package came for the emperor, on the outside was written Nightingale.

“Here’s a new book about our famous bird,” said the emperor, but it wasn’t a book. It was a little work of art lying in a box: an artificial nightingale that was supposed to resemble the real one, but it was studded with diamonds, rubies and sapphires. As soon as you wound the artificial bird up, it would sing one of the songs the real bird could sing, and the tail bobbed up and down and sparkled silver and gold. Around its neck was a little ribbon, and on the ribbon was written: “The emperor of Japan’s nightingale is a trifling compared to the emperor of China’s.”

“It’s lovely,” they all said, and the one who had brought the artificial bird was immediately given the title of Most Imperial Nightingale Bringer.

“They have to sing together. A duet!”

And so they had to sing together, but it didn’t really work since the real nightingale sang in his way, and the artificial bird sang on cylinders. “It’s not its fault,” said the court conductor. “It keeps perfect time and fits quite into my school of music theory.” Then the artificial bird was to sing alone and was just as well received as the real bird. Moreover it was so much more beautiful to look at, for it glittered like bracelets and brooches.

Thirty three times it sang the same song, and it never got tired. People would gladly have listened to it again, but the emperor thought that now the live nightingale should also sing a little—but where was it? No one had noticed that it had flown out of the open window, away to its green forest.

“What’s the meaning of this?” cried the emperor, and all the members of the court scolded the bird, and thought that the nightingale was a most ungrateful creature. “We still have the best bird,” they said, and then the artificial bird had to sing again, and that was the thirty-fourth time they heard the same piece, but they didn’t quite know it yet for it was so long, and the conductor praised the bird so extravagantly. He insisted that it was better than the real nightingale, not just in appearance with its many lovely diamonds, but also on the inside.

“You see, ladies and gentlemen, Your Royal Majesty! You can never know what to expect from the real nightingale, but everything is determined in the artificial bird. It will be so-and-so, and no different! You can explain it; you can open it up and show the human thought—how the cylinders are placed, how they work, and how one follows the other!”

“My thoughts exactly,” everyone said, and on the following Sunday the conductor was allowed to exhibit the bird for the public. The emperor also said that they were to hear it sing, and they were so pleased by it as if they had drunk themselves merry on tea (for that is so thoroughly Chinese), and they all said “Oh” and stuck their index fingers in the air and nodded. But the poor fisherman, who had heard the real nightingale, said, “It sounds good enough, and sounds similar too, but there’s something missing. I don’t know what.”

The real nightingale was banished from the country and the empire.

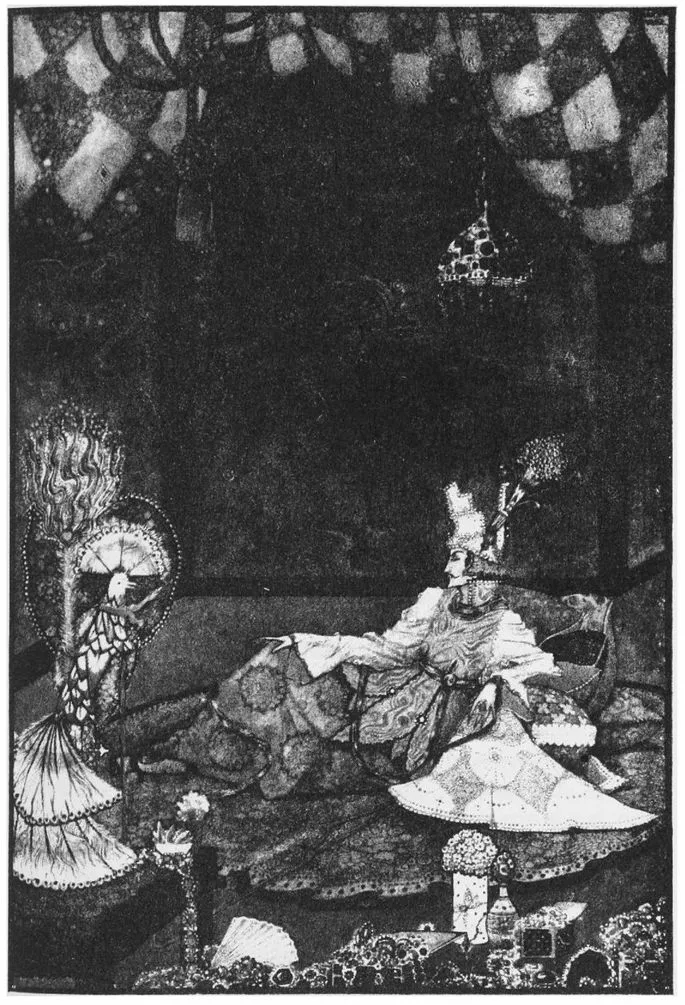

The artificial bird had its place on a silk pillow right by the emperor’s bed. All the gifts it had received, gold and gems, were lying around it, and it had been given the title of Most Imperial Nightstand Singer of the First Rank to the Left because the emperor considered the side towards the heart to be the most distinguished. The heart is on the left side also in emperors. The Royal Conductor wrote twenty-five volumes about the ar-tificial bird that were very learned and very long and included all the longest Chinese words. All the people said that they had read and understood the books. Otherwise they would have been stupid, of course, and would have been thumped on the stomach.

The artificial bird had its place on a silk pillow right by the emperor’s bed.

It continued this way for a whole year. The emperor, the court, and all the other Chinamen knew every little cluck in the artificial bird’s song, but they were therefore all the more happy with it—they could sing along, and they did. The street urchins sang “zizizi, klukklukkluk,” and the emperor sang it, too. Yes, it was certainly lovely.

But one evening, as the artificial bird was singing beautifully, and the emperor was lying in bed listening, there was suddenly a “svupp” sound inside the bird, and something snapped: “Surrrrrr.” All the wheels went around, and the music stopped.

The emperor leaped out of bed at once and had his court physician summoned, but what good could he do? So they called for the watchmaker and after a lot of talk and a lot of tinkering, he managed to more or less fix the bird, but he said it had to be used sparingly because the threads were so worn, and it wasn’t possible to install new ones without the music becoming uneven. This was a great tragedy! The artificial bird could only sing once a year, if that.

1 comment